- Articles

Spies of the Cold War

The Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations by Richard C. S. Trahair was published by Greenwood Press, (Westport, Connecticut) in 2004. It is 473 pages. It consists of nearly 300 A to Z entries of both spies and secret operations as the main text in 350 pages. There are the usual introductions, as well as a useful Chronology (1917-2003), Glossary, and Index, contained in pages 351 to 473.

This tome is a useful addition to the literature. It is based on published material and secondary sources only, and as a conventional, encyclopedia format, it is a sensible decision by the author not to use unconfirmed primary sources. Nevertheless, it is a suspenseful narrative of the espionage contest between the American eagle and its allies, on the one hand, and the Russian bear and its satellites, on the other. Necessarily the tome extends beyond the limits of the cold war, well before World War II and after the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1991.

Given the passage of time and the publication of espionage material since the crumbling of the USSR, there are two welcomed threads of information stemming from this tome. This information goes beyond the authoritative disclosure of secrets revealed in the wake of the publication of the work of the great Soviet defector, Oleg Gordievsky (1938-), in collaboration with British Professor Christopher Andrews,(1) and the fantastic archives of Russian defector Vasili Mitrokhin (1922-2004). The Mitrokhin Archives cover mostly foreign activities of the USSR’s First Chief Directorate up to 1984; it was perused by the authors and the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) from 1992, and published beginning in 1999.(2)(3) In fact, Mr. Trahair relies heavily on these authors, but in addition he has utilized other published sources to fill the gap from 1984 to 2003, as well as to cover other Soviet spy and security Directorates of the KGB and GRU. Imagine if Soviet defector KGB Colonel Vasili Mitrokhin had stayed in his place at the Russian archives at Yasenevo until the collapse of the USSR in 1991. It would have cut short the career of the two most heinous spies in U.S. history: The perverted FBI agent Robert Hanssen (1944-) and the turncoat CIA agent Aldrich “Rick” Ames (1941-)!

As a result of the expanded coverage in this encyclopedia, we learn of the little known audacity of Vladimir Vetrov (1928-1983), a KBG officer of Department T, who at great personal risk remained a defector-in-place for the West. Via France, he helped the West curb the theft of technology by the Soviets and fight the modus operandi of the KGB espionage activities. The strain took a toll on him; he made grave mistakes, was detected, and executed in 1983. We learn also about unusual spies, little mentioned in the spy literature. A despicable case is that of the South African Naval officer, Dieter F. Gerhardt (c. 1935-), a traitor who spied for the Soviets for 20 years. His motives were simple: ubiquitous greed and revenge for the alleged mistreatment of his German father by the pro-British government of South Africa during World War II. It must be added it was our Russian Vladimir Vetrov who informed the CIA of Gerhardt treasonous espionage for the USSR.

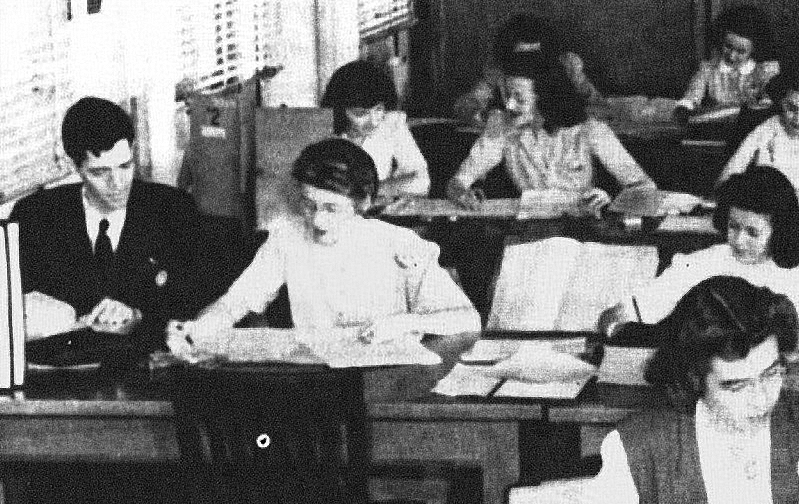

The encyclopedia also details the life of heroes; we have mentioned Vetrov already and will note others. Amongst them is the American linguist and mathematics genius, Meredith Gardner (1913-2002). Here is the man who in 1948 was assiduously deciphering the duplicitous, secret communications of the Soviets between 1944-1945 (Venona files), when the Russians were supposedly our allies in fighting the Nazis. The young whiz kid Gardner helped FBI agent Robert Lamphere (1918-2002) catch traitors like Judith Coplon (1948), while our MI-6 British liaison, the traitor Kim Philby (1912-1988), looked over his shoulder as Gardner worked on Venona! Meredith Gardner retired from the National Security Agency in 1972 to pursuit personal endeavors.

The Venona intercepts identified or confirmed the treasonous espionage activities of Judith Coplon (1921-), the Rosenbergs (the only nuclear spies executed in 1953), Donald Maclean (1913-1983) the British foreign diplomat and one of the Cambridge “Magnificent Five” spies; Ted Hall (1925-1999) and Klaus Fuchs (1911-1988), nuclear physicists and traitors in the Manhattan Project, etc.

Another unspoken hero not sufficiently recognized was the defector-in-place Michal Goleniewski (1922-1993) who crossed over the freedom barrier in 1959. The “powerful built” Pole had a “commanding presence” and had been a KGB agent as well as deputy Chief of Polish Military Intelligence. Appropriately code-named SNIPER by the CIA, he exposed the treason of the infamous George Blake (1922-2020), who caused the deaths of so many Western agents and revealed secret operations like the Berlin Tunnel to the Soviets. Goleniewski also identified the equally atrocious German double agent, Heinz Felfe (fl. 1950-1963), the KGB man in West Germany who subverted the Gehlen Organization after World War II (1951-1961). Goleniewski exposed the operations and identified hundreds of other Soviet spies working for the Polish (SB) or Soviet intelligence services (KGB or GRU). He died in 1993, not 1972 as listed by Trahair.

And so I would be remiss if, in praising this book, I also do not point out a few shortcomings. Mr. Trahair is a good researcher; nevertheless he has a penchant to relate with obvious delight the peculiarities, which may be understandable, but also the gossipy eccentricities displayed and possible errors that might have been committed by some of our heroes. As a trained psychologist, Mr. Trahair should be able to comprehend the incredible strain under which Soviet defectors-in-place operated, working behind the iron curtain at the risk to their (and their families’) lives. The strain and consequent change in their personalities may not subside even after they have reached relative safety. They continue to live, even after their identities have been changed, in constant fear of assassination under the KGB’s “death in absentia” sentences. So who is to judge from the armchair comforts of academic life such eccentricity, as Goleniewski’s probably spurious claim he was descended from Czar Nicholas II, and then referred to the invaluable service he provided to the West as “curious unreliability”? In the case of Anatoly Golitsyn (1926-2008) and James Angleton these eccentricities were more profound and serious and affected the intelligence and counterintelligence (CI) capabilities of the West and are therefore, not only excusable but critical to the narrative, but in the case of Goleniewski, Elizabeth Bentley, and even Moise Tshombe (1917-1969), and a few others, all ultimately on the side of freedom, the gossipy comments are misleading, disparaging, and gratuitous.

Another irksome observation is that Mr. Trahair follows the well-blazed, politically-correct path of others in describing the “Red Menace” and the career of U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957; McCarthyism).(4) The intimation is that these events produce unwarranted, “irrational fears” (page 415), and yet this tome itself describes in incredible detail the vast network of Soviet espionage that was being conducted even as Senator McCarthy was making his denunciations. Soviet espionage was in fact undermining the West, despite the cavalier statement that it took place “in a fear-ridden background, between 1950-1953,” as opines Mr. Trahair, when Senator McCarthy was investigating “with irrational fears” communist infiltration of the U.S. government. Consider the U.S. activities and circle of the illegal master spy, Colonel Rudolf Abel (1903-1971), who was also the case officer for spies Lona Cohen (1913-1992) and Morris Cohen (1905-1995); the Portland spy ring headed by Soviet illegal Gordon Lonsdale (1922-1977) in Great Britain, a spy ring, incidentally, exposed by Michal Goleniewski; the treason committed by high government officials, Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White, and several other spy rings in the FDR administration, not to mention the greatest espionage of all — the stealing of atomic secrets from the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos by several spy rings (e.g. the Rosenbergs) and involving several nuclear scientists (e.g., Ted Hall, Klaus Fuchs, etc.), just a few years before!

Mr. Trahair also seems to take singular pleasure in describing Operations the CIA conducted in an attempt to fight the KGB and the Soviets on a more equal footing, but those operations failed or embarrassed the CIA; these include Operations Chaos, Congress, Artichoke, Corona, etc. In discussing the mysterious death of Frank Olsen (1910-1953) and Operation Artichoke, the author seems to meander into “conspiracy theories” and to encourage the Olsen family “to not let the matter rest.” (p. 212) In deriding Operation Congress, Trahair took exceptional pleasure quoting and paraphrasing a CIA critic, Francis Saunders, at length: “In her account of the CIA’s influence on intellectuals, Saunders (1999) writes, with irony, that it was the same set of people who had been raised on classical literature and educated at America’s foremost universities who, after World War II, recruited Nazis, manipulated democratic elections in foreign lands, administered LSD to subjects without their consent, opened their citizens’ mail illegally, funded dictatorships and plotted assassinations — all in the interest of securing an empire for the United States. This use of irony for criticism meets resistance in the work of CIA apologists Richard Bissell (1996) and William Colby (1987).” (Because quotation marks were not used, Trahair does not tells which are his words and which are Ms. Saunders.)

There are many examples of controlled subtle and not so subtle instances of leftist ideological bias and anti-Americanism just brewing under the surface. Consider the usual treatment of Soviet defectors or Russian double agents working for the West. All their personal defects are spotlighted. In Trahair’s mind, they were all enamored of the good life in the West, or invariably afflicted with character flaws such as greed or lust, and their anti-communism and ideological preference for liberty are downplayed. Take for instance General Dmitry Polyakov (1921-1988; FBI code named TOPHAT), a great Russian patriot and GRU defector-in-place, who finally came over to the West because his seriously-ill, eldest son (who later died) was denied passage to the U.S. by the Soviets for medical treatment. Instead, according to Trahair, Polyakov “became disillusioned with the Russian system and the inadequate salary he received.” The Russian patriot died with a bullet in the back of his head, after courageously denouncing the Soviet system during interrogation and torture. One might consider this example a minor error or simply a difference of opinion, but these errors, misleading statements, and derogatory descriptions occur in the personal description of almost all of the Russian defectors.

On the other hand, consider the treatment of American traitors working in the State Department and other U.S. government agencies in the FDR administration — e.g., Alger Hiss (1904-1996), George Silverman (fl. 1916-1943), Harry Dexter White (1892-1948), etc. They were “young and ambitious idealists who believed they were fighting a secret war against fascism.” With more subtlety, the Cambridge Five spies were usually referred to by the KGB sobriquet, “The Magnificent Five,” etc.

The intelligence services of the West were usually described in terms of moral equivalence and similar modus operandi with those of the repressive Soviet intelligence and security organs. We have already discussed the treatment of the CIA. There were more subtle intimations, as the brief Glossary description of “Sleeper Agents (p. 426).” According to Trahair, “the practice was used more by the Russians than the British.” And yet he gives not one example of “illegal” spies trained by the British and sent to Russia as sleeper agents. The Russians indeed had many famous “sleeper agents” sent to the West, such as the spy couple Lona and Morris Cohen; Willie Fisher (aka., Col. Rudolph Abel), who had entries as we have previously mentioned; and the Soviet illegal agent Kaarlo Tuomi, who became an FBI double agent and ultimately an American patriot,(5) but was not even mentioned in the Encyclopedia.

Consider the definition of the Spanish Civil War (p. 426). General Franco was supported by “German Nazis and Italian fascists,” but no mentioned was made of “communists” in the International Brigades or “NKVD” troops and assassination squads sent by Joseph Stalin, only “unofficial British and Soviet support.” And Trahair ends by stating, “the militarists won.”

Consider also how the Cold War began (p. 431). Not according to most authorities with the astounding disclosures of Soviet espionage on their Western allies made by the defector, cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko (1919-1982) in 1945, but “according to some observers,” by U.S. President Harry Truman giving aid to Greece and Turkey in 1947. And British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s views “were clearly right-wing” (p. 429), but no British Labor leader was described as having “left-wing views,” etc.

The encyclopedia describes many obscure and bizarre incidents of espionage, which otherwise would have escaped public notice. I refer for example to the Berlin spy carousel, the Crabb incident, the KGB honeytrap affairs (very effectively used against the French and others), the strange defection of the West German CI chief John Otto in 1954 and his return in 1955, and many other such bizarre incidents. Most interesting is the account, not fully corroborated that an Australian Prime Minister, Harold Holt (1908-1967; PM, 1966-67) was an agent of influence working for China (1929-1967) through the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek all through the bloody, communist dictatorship of Mao Zedong. He disappeared mysteriously in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Melbourne, drowning in the sea or escaping to China.

Another welcomed addition is the notation as to the year of birth and death of the figures discussed and/or approximate dates of their activities, and an effort, it seems, was made by the author to find out the last activities and whereabouts of the spies. We surmise, for example, that at the time of publication of the Encyclopedia (2004), the following alleged spies were still alive: CIA traitor Philip Agee (1935-2008) who died in Cuba; accused spy Felix Bloch; communist agent Judith Coplon; double agent George Blake (in Russia); Soviet spy Günter Guillaume, who in 1974 brought down the government of West German Chancellor, Willy Brandt (1913-1992) and who was awarded the “Order of Lenin,” and given a dacha in the Soviet Union, etc.

Nevertheless, the Encyclopedia is not exhaustive and has notable omissions. For example there are no entries for Boris Yuzhin, Valery Martynov, and Sergei Motorin. These were KGB officers working for the FBI as double agents. They were betrayed by Aldrich Ames and Robert Hansen. The last two were referred to M & M and were executed by the Soviets. Yuzhin was sent to the gulag and later emigrated to the U.S. Adolf G. Tolkachev, a Soviet engineer and super-spy double agent for the CIA, was only mentioned in passing and no formal entry made under his name. There were other significant omissions. There are also errors of fact. For example, we mentioned Goleniewski’s dates, and Günter Guillaume himself was thought to be alive, when in fact he had died in 1995.

There are also complex errors of fact, due to either wrong sources or/and incorrect interpretation of the facts stemming from political bias. An example of this is found in the Amerasia scandal in which Trahair asserted that the diplomat John Stewart Service was a victim of the Red Scare, when in fact he was a full-fledged communist fellow traveler, rooming in Chungking with two other traitors, the Chinese Chi Chao-ting, and FDR administration official Solomon Adler. All three of these men spread disinformation about alleged venal conditions in the Nationalist government, calumniated Chiang Kai-Shek, and praised Mao-Tse Tung. Information from defectors and the Venona files have verified this concerted campaign was Soviet created disinformation, propagated by these Soviet spies and agents of influence to tilt American opinion away from Chiang and the American government from rendering the needed assistance to the Nationalists, while helping Mao seize control of China.

For the fastidious, there are also a number of typographical and grammatical errors sprinkled throughout the narrative. One more final detraction is the lack of any illustrations, no photos of either operations or the spies. A series of photos in the front cover of this book have no identification as to who these people are or to whom the images belongs, which is unconscionable. Nevertheless, with the aforementioned caveats, this encyclopedia is recommended, essential for the spy aficionados, as well as a ready reference source for the student of history and espionage, and therefore, it is highly recommended with a 4-5 star rating.

References

1. Andrew C, Gordievsky O. KGB: The Inside Story. HarperCollins Publishers. 1990.

2. Andrew C, Mitrokhin V. The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive. Basic Books, 1999.

3. Andrew C, Mitrokhin V. The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World. Basic Books, 2005. This book was published after the Encyclopedia and could not be used or included as a reference. Nevertheless, it is a great book that continues to bring forth revelations from the Mitrokhin Archives.

4. I would recommend Conservapedia for an excellent article on the life of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

5. Barron, J. KGB : The Secret Work of the Soviet Secret Agents. Reader’s Digest Press, 1974.

Additional Recommended Reading

Comrade J: The Untold Secrets of Russia’s Master Spy in America After the End of the Cold War by Pete Earley

Cuban Espionage: The Saga of Florentino Aspillaga and the Assassination of JFK

The Astounding Case of Soviet Defection Deception

China — spies, sexpionage, and cyber wars against America

Roosevelt and Stalin: The Subversion of FDR’s Government by Communist Traitors and Fellow Travelers

Farewell: The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud

From courageous widow to avenging spy! A book review of The Widow Spy (2012)

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise (2002) and of numerous articles on political history and Soviet communism, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011), “Stalin, Communists and Fatal Statistics” (2011), and the Political Spectrum.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Spies of the Cold War. HaciendaPublishing.com, February 28, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/spies-of-the-cold-war/.

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive essay for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not appear in Trahair’s Encyclopedia. This is an expanded and illustrated version of a book review in Amazon posted here exclusively for the well-informed readers of HaciendaPublishing.com.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.