- Articles

The October Horse — Civil War in Ancient Rome and the Death Knell of the Republic!

The October Horse (2002) is the sixth tome in the “Masters of Rome” series of historic novels by Australian author Colleen McCullough. It spans the turbulent years of Roman history from 48 B.C. to 41 B.C. Beginning with Julius Caesar’s campaign in Egypt and his romantic and political relationship with Cleopatra VII, Pharaoh of Egypt, the book proceeds with Caesar’s war against the Republicans in Africa, led by the indomitable Marcus Porcius Cato, Metellus Pius Scipio, King Juba of Numidia, and Titus Labienus. In Spain and on the high seas, the Republicans are led by Pompey Magnus’ sons, the maritime admirals, Gnaeus Pompey Jr. and Sextus Pompey. The book proceeds with the victories of Julius Caesar and his establishment of a virtual tyranny in Rome as dictator perpetuus, which ultimately ends with his assassination on the Ides of March in 44 B.C.

The assassination conspiracy was led by the Republican Liberators, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, as well as Caesar’s former comrade-in-arms, Decimus Brutus and Gaius Trebonius, who deplored Caesar’s dictatorship and his virtual abolition of the Republic and the mos maiorum. The book proceeds with the emergence of young Octavian as Caesar’s heir and his struggle for power with Marcus Antonius; their alliance with the formation of the Second Triumvirate (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as the third man in power); the enforcement of proscriptions that decimate the old families of Rome and bring money to the coffers of the Triumvirs; the vile execution of Marcus Tullius Cicero; the battle of Philippi in 42 B.C., and the suicides of Brutus and Cassius. Predictably, following the destruction of all the Republican forces and the death of the Liberators, the contention for supreme power resumes between Octavian and Marc Antony.

The idolatry of Julius Caesar by the author continues in this book, as she lavishes praise over her idol, his untarnished dignitas, his unbounded auctoritas, his perfect physique, his brilliant brain, etc., to the detriment of the book, and the entire Masters of Rome series, which has otherwise been well researched and dramatized.

This sixth tome in the series, then, continues where the previous book ended with Julius Caesar in Egypt after Pompeius Magnus’ tragic assassination by the complicity of Egypt’s ruling clique comprising the Lord High Chamberlain, the eunuch Potheinus; Egyptian general Achillas; and the tutor of the boy-king Ptolemy XIII, Theodotus. With civil war raging, Caesar supports the Pharaoh Cleopatra VII against her brother-husband Ptolemy XIII. McCullough does an excellent job explaining the interrelationships of the divided Ptolemaic House and the balance of religious and political power between the cities of Memphis and Alexandria, respectively.

Most interesting is the description of the Elephantine Nilometer used every year to gauge the expected life-saving inundations of the Nile, which predict whether Egypt will enjoy the Cubits of Plenty (i.e., inundations 18-32 feet), or suffer disasters under the Cubits of Death (less than 18 feet) or the Cubits of Surfeit (i.e., deluge with inundations over 32 feet).

It is in Egypt where we learn that the demigod Caesar at age 52 is vulnerable to human maladies. He suffers a gastric illness and then an epileptic seizure, which explains, at least in the mind of McCullough, why events went awry during the Roman involvement in the internecine war in Alexandria. Since much of this mayhem and destruction — particularly the partial burning of the Museum (i.e., the fabulous Ptolemaic Library) of Alexandria, the destruction of a million precious books, and much of the city and harbor — resulted to a significant degree from Caesar’s doings, it is glossed over with moral neutrality. This objectivity in passing moral judgment is not granted to the enemies of Caesar, the hated Republicans (the Optimates) and boni men, when they act to preserve their political power or even uphold the mos maiorum (i.e., the unwritten constitution and the venerated and old traditions of the Republic).

Returning to Caesar’s noted but troubling affliction of epilepsy, it is obvious the author has a difficult time dealing with it. How can a perfect demigod, descended from the goddess Venus (and Aeneas) and the god of war, Mars, be afflicted with such a mortal’s malady as epilepsy? Events are arranged thus, so in the court of Alexandria a wise Egyptian high priest informs Caesar: “You have had an epileptic fit, but you do not have epilepsy.” McCullough explains the seizure was brought by his illness and fatigue.(1) Later in the book, she decided the seizure was due to hypoglycemia, and Caesar adds to his entourage an Egyptian physician who successfully prescribes him fruit juices at frequent intervals.

After demonizing the great Marcus Porcius Cato in several of her books, disparaging his intelligence, reminding us time and again of Cato being a “slow learner,” a “slow reader,” a “block head” (“not bright as Caesar”), suddenly a historic Cato springs forth from the pages of this historic drama! It happens following the defeat of Pompey Magnus (“the Great”) at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C., during two relatively short but memorable events. One is Cato’s leading the epic march of ten thousand defeated Pompeian troops loaded with the sick and wounded, not to mention camp followers and families, a real migration over the barren wasteland and coast of North Africa — i.e., from Cyrenaica to Utica in Africa Province. Cato the Younger has finally learned to lead men in crises, not because of any inner light as a staunch Stoic philosopher or military gift, but because, according to McCullough, Cato has read and digested Caesar’s dispatches to the Senate, later his celebrated Commentaries of the Gallic Wars!

The other event in which Cato comes to life is his competent administration and consolation of the people of Utica in the final moments before the collapse of the Republican cause in Africa: At Utica, Cato takes firm and decisive control, ends the perpetual squabbles of Republican leaders, and organizes the city’s defenses. Later, just before his death, he organizes the escape of the few surviving Republicans.

Nevertheless, as described in previous reviews,(2,3) the vituperations against Cato the Younger and all the Republican leaders, the hated boni, continued in this volume. For McCullough, the boni lack integrity, are driven by selfish motives, and their malice is all-consuming. Metellus Scipio, Pompey the Great’s father-in-law, is portrayed not only as a dull individual, but maliciously and without historic evidence is accused of “wallowing in little boys and pornography.” This is an unfounded accusations that calumniates a historic figure purely on the basis of the McCullough’s political bias, certainly not worthy of a noted author of historic novels, who has claimed, “In this Roman series I have severely limited my novelist’s imagination, and do not allow it to contradict history.”(4)

The Republicans, when speaking even among themselves vituperate, ” bark,” “howl,” “roar,” “growl,” “speak between their teeth,” and are envious block heads, who, with few exceptions, are maliciously and perniciously hostile to enemies and friends alike. Caesar’s men, on the other hand, commiserate in friendship and largely speak to each other with sympathy, kindness, and intelligence. McCullough can get quite nasty and vulgar, when making Republicans speak to each other. Consider what she makes Cassius say to Brutus to needlessly insult him in an invented quarrel and improbable temper tantrum: “Personally, I think you’re a gutless cocksucker — You’ll always provide the orifice! At least I’m the one who shoves it in, which makes me a man.”(5)

Likewise we should also remember from her earlier books most of the Populare demagogues — heading the list Fulvia’s first two husbands, Publius Clodius Pulcher and Gaius Scribonius Curio — have all been described as “brilliant.” And when it comes to Caesar, according to the author, the demigod walks with grace, thinks logically, speaks beautifully and acts correctly, according to the mos maiorum — while all along, historically, Caesar is doing quite frequently the opposite. Take for instance, when McCullough makes Caesar say, “government must have opposition, but not from the boni, who oppose for the sake of opposing, not on soundly based, genuine, and thoughtful analysis.”(6)

What nonsense is this? The Republicans, led by the boni, were fighting no doubt to protect their prerogatives, but also to preserve the mos maiorum and Republican governance, as well as to prevent usurpations and being cowed by military marches on Rome by demagogic generals! And a mere page later, in full contradiction to his previous statement, Caesar more sincerely exhilarates, “it is terrific to be dictator — saves huge amounts of time dealing with matters I know I’ve fixed in exactly the fairest and most proper way.”(6) And that Caesar has no more children with Servilia, Calpurnia, or Cleopatra is his choice — no fault of the perfect demigod. Stephanie Dray, author of Lily of the Nile, wrote in her review of this book, “Caesar said he wanted neither to be a King nor a God. In her new book, The October Horse, Colleen McCullough makes him both.” Precisely!

Following several military defeats upon the Republican generals, Cato at Utica finally decides all is lost and rather than submit to Caesar, he chooses to commit suicide. Caesar, with novelistic sophistry invented by McCullough, blames Cato for everything. “Without Cato there would not have been a civil war. It is for that I can not ever forgive him.” And when Caesar learns of Cato’s Socratic reminiscences and the Phaedro’s discussion the evening before his death, he supposedly rejoices: “Oh Cato with your longing for an immortal soul, your fear of dying; what is there to be afraid of in dying?”(7) Thus Caesar, who later stated he preferred a quick death, and got it by assassination, is supposedly braver than Cato, who faced death by choice and with his own hand!

According to McCullough, Sallustius Gaius Crispus (Sallust; 86 B.C. to 34 B.C.), a politician friend of Caesar and later a noted Roman historian, speaking to Caesar, “blames the whole Catiline Conspiracy on Cicero. He [Cicero] manufactured a crisis to distinguish his consulship above banality.”(8) Unfortunately on this point, McCullough’s scholarship failed her. She must not have read Sallust’s little book, Conspiracy of Catiline, with care. The historian correctly blamed Catiline for the turbid but definitely dangerous and treasonous affair, even though he was a political enemy of Cicero and populist politician. Sallust’s account is an unbiased and objective account of the conspiracy, which was a genuine peril to the Republic. Cicero as Consul in 63 B.C. had indeed saved Rome and earned the title of Pater Patriae (“Father of his Country”)!

As for Caesar’s assassination, the conspiracy was all about advancement of careers and hatred, and nothing to do with saving the Republic. According to McCullough, the idea of converting it to a patriotic act was a sham deliberately contrived for the self-advancement of the conspirators. It was pure envy of the demigod that propelled them to kill Caesar, who was a martyr, perfection personified, a demigod who deservingly became a god, Caesar divus!(9)

Marc Antony, according to McCullough, had at least a passive role in the conspiracy, so Octavian a mere 18-year-old youth and Caesar’s grand-nephew and legal heir, rightly picks up the god’s political mantle and becomes the next best thing on the Roman horizon. Octavian now receives the accolades Julius Caesar should have received. The rest of the Romans are bumbling bunglers, rapacious and short-sighted idiots and sycophants. One wonders how the ancient Roman Republic built enduring roads and breathtaking aqueducts and other wonders of engineering, excelled in oratory and the rule of law, came to dominate the Western World, and safeguarded Graeco-Roman civilization from the barbarian hordes threatening the thousands of miles of frontiers for so many centuries. Not to mention, it also provided the basis and infrastructure for the lasting empires that followed in the West and in the Eastern Byzantine Empire.

Nevertheless, McCullough agrees with Octavian the end of the mos maiorum and the Republic is a good thing, and young Octavian, who now also promotes the deification of Julius Caesar as Caesar divus and calls himself Caesar, is the man — or rather the new demigod as divi filius (“son of the god”) — to do it.

In conclusion, this tome can only be recommended with the same caveats I have more or less delineated for each of the previous books in this Masters of Rome series, or as entertaining reading, simply because of the suffusing political bias and prejudices saturating these historic novels, bias that remains a looming distraction in her histories. As I pointed out as early as the first review of her book series: “…her scholarship is outstanding, and her literary abilities certain; the problem lies elsewhere, apparently her politics and her prejudicial bias for the Populares faction at the expense of the Optimates and the historical veracity she claimed.”(10) To which we should add, her adoration of and infatuation with strong men and autocratic dictators, beginning with Gaius Marius, then Julius Caesar, and to a lesser extent, Caesar Octavianus divi filius (Octavian) — at the expense and to the detriment of other eminent historic figures.

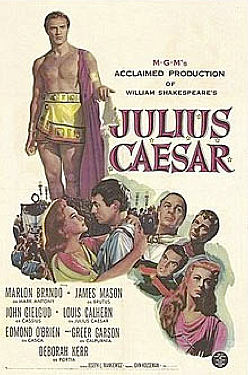

It is of interest that in one of her tomes McCullough commented — i.e., decrying critically — on the general renditions of Hollywood movies on the Roman Republic. And yet in many aspects of their personas, Roman figures depicted in such romanticized film version as Julius Caesar (1953; based on Shakespeare’s play) — e.g., Brutus, Cassius, Caesar, Marc Antony, and even Porcia, played by James Mason, John Gielgud, Calhern Louis, Marlon Brando, and Deborah Kerr, respectively — the characters sometime come closer to the truth than in McCullough’s novels. Brutus, for example, is by far more accurately depicted in this movie than in McCullough’s book; and if still in doubt, check out Plutarch and other ancient authors! This magnificent film, in fact, I would recommend to the reader, as a partial counterpoint and different viewpoint to McCullough’s tendentious The October Horse.

Thus, as I complete the reading and review of the penultimate book in the series, I have no reason to alter my previous verdicts. In fact, her prejudices, historical bias, and her infatuation with Julius Caesar in the last three volumes — which surpasses by far that which she incurred with Gaius Marius, the hero of her first two books — have become even more serious, detracting more and more from her narrative and, regretfully, from her historical accuracy. The distortion of the conduct and true character of many of the opposing historic figures, usually the political enemies of her heroes, as I have outlined, is particularly disturbing. The student of history should therefore read additional non-fictional sources to clarify facts and personalities, and correct misconceptions that may have inadvertently crept in from depending solely on Colleen McCullough for accurate historical characterization and interpretation of historical events.

Read Dr. Faria’s review of the previous installment or the next installment of McCullough’s “Masters of Rome” series.

References

1) McCullough C. The October Horse. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 2002, p. 88.

2) Faria MA. Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar. A book review of Fortune’s Favorites (1993) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 8, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/fortunes-favorites-in-ancient-rome–sulla-pompey-crassus-and-caesar.

3) Faria MA. Caesar’s Women — McCullough’s Idolatry and Politics in Ancient Rome. A book review of Caesar’s Women (1997) by Colleen McCullough. Haciendapublishing.com, August 14, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesars-women-mcculloughs-idolatry-and-politics-in-ancient-rome.

4) McCullough C. Fortune’s Favorites. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 1993, p. 865.

5) McCullough C. The October Horse. Op cit., p. 697.

6) Ibid., p. 214-216.

7) Ibid., p. 304-305.

8) Ibid., p. 351.

9) Ibid., p. 361-408.

10) Colleen McCullough, “Masters of Rome” Box Set. https://bookreadfree.com/252094/6223195.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria, Jr., a medical historian, is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise (2002) and of numerous articles on politics and history, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011), The Political Spectrum — From the Extreme Right and Anarchism to the Extreme Left and Communism (2011); Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery (2013), etc., all posted at his website HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. The October Horse — Civil War in Ancient Rome and the Death Knell of the Republic! HaciendaPublishing.com, November 17, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-october-horse–civil-war-in-ancient-rome-and-the-death-knell-of-the-republic.

(The October Horse by Colleen McCullough. 2002. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 792 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s The October Horse. An unillustrated version of this article appeared also in Amazon.com book reviews.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

3 thoughts on “The October Horse — Civil War in Ancient Rome and the Death Knell of the Republic!”

This day in History (September 4, A.D. 476): The Fall of the Western Roman Empire — Romulus Augustus, the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, is deposed by Odoacer, a German barbarian who proclaims himself king of Italy.

Odoacer was a mercenary leader in the Roman imperial army when he launched his mutiny against the young emperor. At Piacenza, he defeated Roman General Orestes, the emperor’s powerful father, and then took Ravenna, the capital of the Western empire since 402. Although Roman rule continued in the East, the crowning of Odoacer marked the end of the original Roman Empire, which centered in Italy… https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/western-roman-empire-falls

The Fall of the Roman Republic, though, 500 years earlier occurred after the defeat and death of the Pompeians: Pompey the Great (48 B.C. at Pharsala) and his sons Gnaeus and Sextus; Cato (at Utica) to Caesar; then Cicero assassinated by orders of Mark Antony; and finally the defeat of the last Republicans, Brutus and Cassius to Mark Antony and Octavian (42 B.C. at Philippi). — Dr. Miguel Faria https://haciendapublishing.com/the-october-horse-civil-war-in-ancient-rome-and-the-death-knell-of-the-republic/

The members of our senate may be similar to the Roman Republic at the nadir of the Republic and the sacking of Rome.—N.L. (FB, Dec, 16, 2022).

N.L. “… at the nadir of the Republic and the sacking of Rome.” We need clarification for my intelligent friends. It must be one or the other: The nadir of the Republic was c. 49 BC with Julius Caesar, but then the Roman Senate fought for the Republic with Pompey at the helm. Unfortunately the Senate and Pompey lost to Caesar’s battle hardened troops, and that marked the death knell of the Republic. The early sacking of Rome took place during the burgeoning Roman Republic in 390 BC before Rome was ready for the invading Celts. For 800 years the Republic was supreme. Recall the the story of Consul Laenas and the Seleucid King Antiochus IV. But 800 years later during the decline of the Western Roman Empire headed by emperors, Rome was sacked again during the 5th century, sequentially in AD 410 by the Goths led by Alaric; AD 455 by the Vandals led by Gaiseric, and AD 476 by a conglomerate of Germanic tribes led by Odoacer. I don’t know which you these scenarios you refer to, but at any of the Republican stages the Roman Senate was more courageous and principled than ours, at least since the time of Bush 41! You must mean during the decadent Empire in the 5th century of the Christian era. I recommend the historic series of novels by Colleen McCullough with the caveats that I discuss in my reviews.— Dr. Miguel A. Faria

The history of civilization began with marauding tribes raiding villages, killing men or enslaving them, raping or capturing women and children for slavery. Crops stolen. Burning and pillaging of villages and rural communities, where only the few resourceful survived, no roads, no bridges, no sanitation, no hygiene, no potable water except streams. The Greeks and Romans changed that in Europe and brought civilization—arches, concrete, bridges, vaults, domes, aqueducts, stone buildings with courtyards, baths, marble columns, surplus food, laws, philosophy, art, etc. The Romans were surrounded by barbarian tribes—Goths, Alemanni, Celts, Bulgars, Scythians, Turks, Parthians, etc.—who threatened the Roman frontier on all fronts and coveted the empire. Yes, the Romans might have been cruel but they had to be in order to survive and protect their borders and civilization. In turn, they conquered and eventually expanded to leave us an enduring legacy. The Germans came to the attention of the Romans after they crossed the Rhine to conquer the Gauls, who asked the Romans for assistance….Yes, the Romans were cruel but they had to be tough in order to protect their empire and to rule Europe and the Mediterranean for nearly two millennia! If there had been no Romans—there would be no surviving aesthetic Greek culture, Western civilization, or Christianity. The nearest civilizations to the Graeco-Romans were the Persians, Parthians, and Sassanians. And if these eastern potentates had won, we would be speaking Arabic or Farsi today, part of the Arab or Iranian world—Muslims. How is your Arabic? But since the Romans are part of Western Civilization, they are vilified in the popular culture and academia that would rather us be communist or anything other than American and part of Western civilization. Think about it when you hear our Graeco-Roman heritage slandered by those indoctrinated by the mainstream liberal media and the popular culture.—Dr. Miguel A. Faria, whose next book in preparation is The Roman Republic, History, Myths, Politics, and Novelistic Historiography (2025) by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK