- Articles

Caesar’s Women — McCullough’s Idolatry and Politics in Ancient Rome

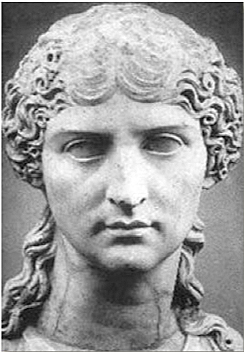

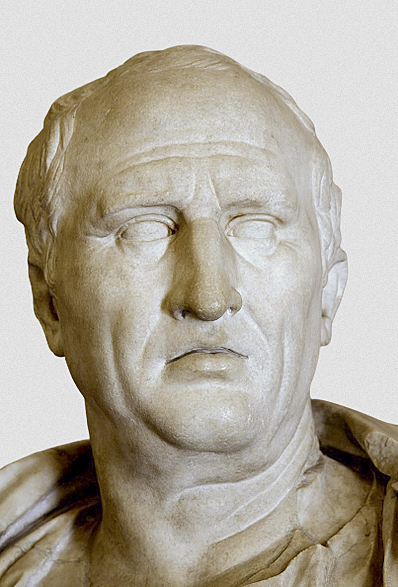

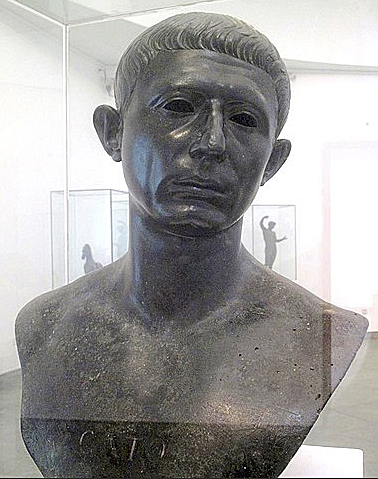

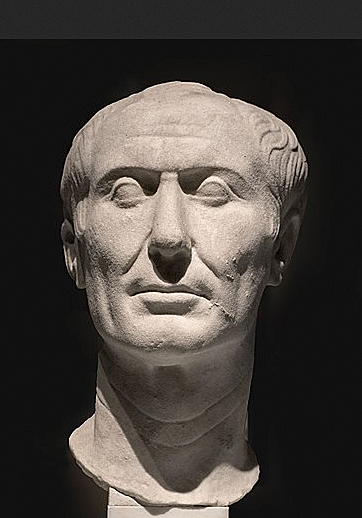

Caesar’s Women (1997) is the fourth installment of the “Masters of Rome” historical book series by novelist Colleen McCullough. The complete series spans the period from 110 B.C. to 27 B.C. This tome covers the eight years of the Late Roman Republic from 67 B.C. to 59 B.C., including the revolt of Aemilius Lepidus; the Conspiracy of Catilina and the passing of the Senate’s Ultimate Decree; the curious episode of the Consul Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus (also an augur) withdrawing to his house to watch the stars and cancel the legislative acts of his very active fellow Consul Julius Caesar; and the sacrilege of Clodius Pulcher, and Caesar’s consequent remark that his wife must be above suspicion. The main characters are Julius Caesar (not unexpectedly given the title of this volume), who is mostly in Rome, intriguing and womanizing, while ironically presiding over Rome’s civic religion as supreme Pontifex Maximus; Marcus Licinius Crassus, the plutocrat; Marcus Tullius Cicero, the great advocate who becomes consul at the time of the Catilina crisis; Marcus Porcius Cato, the unyielding politician and stoic philosopher; Publius Clodius, the young iconoclastic rogue; Marcus Junius Brutus, the studious youngster and heir to the Caepio fortune, who is hen-pecked by his mother Servilia; and of course, Pompey Magnus, who is at this time unquestionably the First Man of Rome.

The women protagonists are those revolving around the life of Caesar: His mother, Aurelia; his mistress, Servilia (and other enterprising females in similar categories); his beautiful and dutiful daughter, Julia; his second and discarded wife, Pompeia Sulla; and the Vestal Virgins. We also have a glimpse at the lives and personalities of other Roman women of some historical importance: Terentia Varro (Cicero’s wealthy and imperious wife), Fulvia (Clodius wife, politically inclined and granddaughter of Gaius Gracchus), Clodia (Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer’s wife, mistress of the lyric poet Catullus, and possible poisoner of her own husband, an ex-consul and conservative senator).

Despite the title, this novel covers the historical period in question at least in Rome (from 67 B.C. to 59 B.C.), not just Caesar’s romantic adventures. Moreover, Caesar’s Women include not only mistresses but also the close female relatives in his family and social circles, women who duly influenced his political life. That is not to say there is no lustful sex, gossip, and romantic intrigues in and outside the bedroom. In fact, the sexual liaison between Caesar and Servilia crosses into the potboiler genre and regrettably hints at outright pornography.(1) I am no prude, and will admit that eroticism in small doses in a historic novel may be a treat if done with finesse, but sex and gross vulgarities in large doses may be a put off to many readers who may have previously enjoyed the first three volumes of McCullough’s historical acumen in novelistic form. For example, the reader will come across such sexual vulgarities and obscenities in Latin as irrumator, fellator, pipinna, cunnus, mentulla, verpa, which she sprinkles throughout her book, translates for our benefit, and fastidiously defines in a glossary that is significantly abbreviated in this tome. The reader should be prepared to encounter “juicy” female genitalia before penetration and the like. Moreover, descriptions of young prepubertal girls is a bit disturbing in that the author describes them with sexual overtones, as if they were sexual nymphs or mature adults — one can only smell the odor of pederasty in the air without the author actually crossing the line into overt pornography. For example, a 15-year-old Brutus is already in love with the 8-year-old Julia (Caesar’s daughter who often is kissed by her father on her lips), and whose lips are “faintly pink as delicious as strawberries.”(2)

My main criticisms stem out of McCullough’s ubiquitous political bias affecting her historical trustworthiness and which become even more accentuated in this volume.(3-5) McCullough has been denying the existence of ideology or political factions in ancient Republican Rome, but in this volume she finally deigns to admit the existence of an ultraconservative faction in the Senate, the boni (i.e.,”the good men”), whom she ardently detests and defines as a “clique.” Typical references to this conservative faction are: “The boni were brilliant at currying favor with the knights”; “Gaius Piso was a choleric, mediocre, and vindictive man who belonged completely to Catulus and the boni“; and referring to Catulus, Bibulus, Lucullus, Cato, and Domitius Ahenobarbus — all boni men — she rails, “odd how all the obnoxious ones stuck together, even in marriage.”(6) No such repetitive blanket, derogatory references were made of even the most obnoxious, populist demagogues — i.e., Appuleius Saturninus, Publius Sulpicious, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, etc., either in previous volumes, or of iconoclastic and irascible populists in this volume, such as Aemilius Lepidus (who marched on Rome), Clodius Pulcher, Decimus Brutus, Marc Antony, not even of the conspirator Sergius Catilina, and God forbid, not of the faultless Julius Caesar, McCullough’s “quintessential Roman.”

Cicero is derided with a vengeance, and his deserving the title of Pater Patriae is cast in doubt with lethal subtlety, while the conspiracy and insurrection of Catilina is treated as if it was of no serious concern to the Republic. Thus the necessity for Cicero’s Senatus Consultum Ultimum (i.e., “The Senate’s ultimate decree to defend the Republic,” imposing martial law) is also brought into question. All the boni conservatives are simply block heads. According to McCullough, Cicero’s reputation has not only been inflated by time, but he was a timid “idiot” and an indecisive “turd”; Marcus Porcius Cato, known to history as the Stoic philosopher, is “thick and narrow”; Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio, “whose ancestry was far greater than his intellect,” is like Cato “thick.”(7) On the other hand, the populist young thug Clodius Pulcher is not only “shrewd” and “brilliant,” but “what he says,” in the mouthpiece of Caesar, “is usually right.”(8) Here is a telling paragraph that refers to Clodius’ circle of “brilliant” populist rogues, including young Marc Anthony, who went around the forum and the Subura wreaking havoc and intimidating citizens:

“Until the execution of their stepfather [a Catilina conspirator], no one had ever taken the Antonii seriously. Or was it that men looked no further than the scandals trailing in their wake? None of the three owned the ability or brilliance of young Curio or Decimus Brutus or Clodius, but they had something in its way more appealing to the crowd the same fascination exerted by great gladiators or charioteers: sheer physical power, a dominance arising out of brute strength.”(9)

And so we are left with disparate incongruity and laughable proposition that the gang of young thugs led by Clodius creating mayhem for the populist cause in Rome are “brilliant” youngsters, whereas the conservative senators, who want to preserve the old ways and traditions of the Roman institutions — i.e., the unwritten constitution or the mos maiorium — of the Republic, are a “clique” of rancorous, obstructionistic old men, narrow, thick heads, led by Cato (who incidentally was younger than Caesar, and Brutus, Cato’s nephew, considerably younger). According to McCullough, the boni were not patriots but cantankerous obstructionists who only wanted to impede the good, conscientious reforms of the quintessential Roman — Julius Caesar. Why? Because they were jealous of the demigod’s intellect and looks, and unjustly insisted (their prescient accusations seemed to have escaped the author) that his goal was to ultimately betray the government, overthrow the Republic, and become dictator for life.

Curiously, in the previous volume, Fortune’s Favorites, Caesar lectures Pompey on the importance of abiding by the laws of Rome. Now in this volume, we have Caesar, once again, turning the table on history and common sense, explaining to Cato why he (Caesar) favored Sulla’s abrogation of the power of the Tribunes of the Plebs because they had been obstructionists and too pliable in the hands of the odious, conservative senators, the boni! McCullough also takes the opportunity to use one of her favorite metaphors as a double entendre by having Caesar, who had allegedly not only cuckolded Cato but had also been carrying on an affair with Cato’s half-sister, Servilia, humiliate Cato without mercy. He tells Cato the Philosopher: “I have more intelligence in my battering ram than you do in your citadel.”(10)

Young Caesar in his teens and twenties is a prodigy without equal; in his thirties now, he can walk on water, while everyone else sinks or floats! He is arrogant, cynical, punctilious, who demeans all that others have accomplished. And yet this is the time when Pompey the Great has conquered for Rome half a world in Spain, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and cleared the Mediterranean Sea of pirates, making it effectively Rome’s Mare Nostrum, while Caesar has stayed at home. True, Caesar won his corona civica (Oak leaf crown) in combat and succeeded in being elected Pontifex Maximus, but compared to the accomplishments of Crassus, who helped Sulla win the battle of the Colline Gate and suppressed Spartacus, or Pompey, who has more than doubled the territories and wealth of Rome, Caesar has done relatively little. Yet Pompey is treated with derision. Crassus, except for his greed, is forgiven, as he is Caesar’s only friend and confidante. In her previous volumes, particularly The First Man in Rome and The Grass Crown, McCullough had characters, such as Rutilius Rufus, give informative and historically accurate speeches that were literary and charming. No more: Cicero has lost his literacy and eloquence, and is no longer “completely reliable”; Pompey’s letters are written like a school child; only Julius Caesar can orate great speeches and write laws as literary masterpieces.(11)

In Caesar’s Women, McCullough continues to deny the existence of “political parties or factions in the modern sense.”(12) The Optimates, she prefers to relegate to a “clique,” preferring as I have mentioned, the term boni for the “ultraconservatives”; but she does finally use the term Populares to refer to some of her demagogic heroes.(13) The fact is that a great divide had been developing in Roman society since the time of the political turmoil that the Gracchi brothers had fomented during the years 133-121 B.C. In the end, the crescendo political strife would culminate with the conflict between Julius Caesar and the Senate that would rend the Republic apart and usher in the Empire.

There might not have been organized modern political parties, but there were definite political factions, two ideological camps — i.e., the Optimates (“the best men,” or conservatives) and the Populares (” the people’s men,” or liberals), vying for the reins of power. The Optimates were fighting to preserve their aristocratic privileges, as well as the mos maiorium, the old ways, traditions, and the unwritten constitution of the Republic, opting to maintain decentralization of power. They represented the interest of the Senate, the old Roman noble families (which had provided at least half of all the consuls in the previous century), and the new nobility (i.e., the nobiles, recently ennobled plebeian or patrician families that had produced men who had served as consuls and thus reached “consular” status).

The Populares were vying to overthrow the old order, so they could become the new masters via the centralization of authority resting on one man, who could use force if needed, and whose power base rested on the support of the lower classes of Roman society. The support of the lower classes was to be preserved by the Populares by the distribution of cheap (or free) grain and games (i.e., “bread and circuses”), the breaking up of latifundia for free land redistribution, and if necessary the most radical measure bandied about — the cancellation of debts. Their champions were the ten Tribunes of the Plebs working through the legislative Assemblies and utilizing their veto power. The legions were to be loyal to the strong man, the popular general at the helm, and not the Senate. (We know how that worked out, not only in the late Republic but also later in the Empire.) All the ingredients were there for the fatal brew, and I can think of no better raison d’être for the inception of political combat and the ushering in of civil war than those two aforementioned, distinct political and ideological camps preparing for war.

As I have stated before, McCullough’s persistent denial of the existence of the Optimates vs. Populares political contest (which despite this denial is still obvious in her books) must be attributed to McCullough’s effort not to make her irrepressible political leanings too obvious in these historic novels for which she has claimed total objectivity and veracity.(1,4,5) McCullough, were she one of her own characters, would be in the vanguard of the popularist onslaught leading at the helm with Clodius and Fulvia in the overthrow of the mos maiorium and the Republic — and to place Caesar as the “First Man in Rome,” even before his conquest of Gaul!

McCullough does have an enchanting moment in her novel that deserves mention: the love match and betrothal of Pompey the Great and Julia. The embellishment of this romance makes this story more charming than the more probable reality of an arranged political match. She is well justified in the embellishment as Caesar really loved deeply the two Julia’s in his family, daughter and aunt, and Pompey ended up loving his various wives with a remarkable intensity and uxoriousness. This is the best segment of the book and it concerns Pompey and Caesar’s daughter, Julia, more than it concerns Caesar!

In the Author’s Notes, McCullough writes: “I have done my research: thirteen years of it before I began The First Man in Rome, and continually since (which sometimes leads to my wishing I could rewrite the earliest books!).”(14) But the problem with this volume lies not in scholarship but in her over prurient style, infatuation with her subject to the detriment of other historic figures, and her political leanings permeating and marring her work.

I have given the previous three volumes thumbs up (i.e., 4 stars out of 5), despite annoying flaws and persistent criticisms. Alas, this book regrettably fails to live up to the expectations of the previous volumes (3 stars). It fails, first among other things, because of the author’s blinding adoration of Julius Caesar, which surpasses the infatuation she had previously incurred with her primer amor, the demigod Gaius Marius, and secondly, because of her insuppressible and increasing political bias and animus permeating and detracting from her work, as I have tried to convey in the above critique. Regrettably, I cannot recommend this book as a stand alone, single volume, but it is still a necessary volume for those of us who have read the previous installments and continue to read the “Masters of Rome” series.

Read Dr. Faria’s review of the previous installment or the next installment in McCullough’s “Masters of Rome” series

References

1. McCullough C. Caesar’s Women. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1997, p. 45-47; 59-61.

2. Ibid., p. 8, 12.

3. Faria MA. The First Man in Rome – The Apotheosis of Gaius Marius. A book review of The First Man in Rome (1990) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, June 4, 2013.

4. Faria MA. The Grass Crown — Ancient Rome: Marius vs Sulla and the Marsian Wars! A book review of The Grass Crown (1991) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, June 6, 2013.

5. Faria MA. Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar. A book review of The Grass Crown (1991) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 8, 2013.

6. McCullough. Op cit., p. 32, 62-63.

7. Ibid. In the voice of various characters or the author: Cato “thick,” p. 348; Scipio’s “intellect,” p. 364; Cicero “a timid idiot,” p. 268, 357 and “turd,” p. 366.

8. Ibid., p. 313, 443.

9. Ibid., p. 387

10. Ibid., p. 399-400.

11. Ibid., p. 409.

12. Ibid., p. 656. In the Glossary, McCullough insists under “Faction” that “Political ideologies did not exist nor did party lines.”

13. Ibid., p. 375-386.

14. Ibid., p. 635.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI), and an Ex-member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2002-05; former Editor-in-chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002). Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Caesar’s Women — McCullough’s Idolatry and Politics in Ancient Rome. HaciendaPublishing.com, August 14, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesars-women–mcculloughs-idolatry-and-politics-in-ancient-rome

(Caesar’s Women by Colleen McCullough (1996). William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 696 pages)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s historic novel titled, Caesar’s Women. A shortened and unillustrated version of this article appeared also in Amazon.com book reviews.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.