- Articles

Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar

Fortune’s Favorites is the third installment of the fascinating “Masters of Rome” series of historical novels by famed Australian novelist Colleen McCullough. The 878-page book opens in 83 B.C., as the triumphant general, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, returns from the East after his successful campaign against King Mithridates VI of Pontus. The book ends with events taking place at approximately 69 B.C. surrounding the rivalry and rise of Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus, while young Julius Caesar is biding his time and foreshadows a political and military career superior to them both, a worthy descendant of Venus and Aeneas!

In this novel, McCullough continues to enhance her work with magnificent maps, a useful glossary, and realistic, hand-drawn sketch portraits of many of the main characters. Her well-researched novel, written in crisp and eloquent prose continues to enchant and makes us marvel at the ancient Roman world, which draws so many parallels with our own. Outright mistakes or errors of fact are few and usually minor. For example, McCullouch claims that after the first century of the Republic most consuls were plebeian, when in fact most consuls in the early Republic were patrician rather than plebeian, which is why a subsequent law was passed legislating that at least one of the two consuls had to be plebeian.

After Sulla’s return from the East with his victorious armies, a second civil war ensues as Sulla battles the remaining Marian forces (i.e., the Populares) in Rome now led by the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna and, after Cinna is assassinated by his own troops, commanded by the consuls Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and Young Gaius Marius.

Sulla defeats his Populares enemies and their Samnite allies with the assistance of his great military lieutenants — i.e., Pompey Magnus (” the Great”), Marcus Licinius Crassus, Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus, Metellus Pius, and Licinius Lucullus. With final victory at the Colline Gate near the northeastern portion of the Servian Wall — Sulla attains supreme power, becomes legally appointed dictator, eliminates his political enemies by his infamous proscriptions, and for the next 3 years sets himself to reconstitute the old Roman Republic along conservative lines and the mos maiorium.

As dictator, Sulla used his powers to enact a series of reforms restoring the power of the Senate, trimming the prerogatives of the Tribal and Plebeian Assemblies, and defanging the demagoguing Tribunes of the Plebs, whose powers had increased immensely over the centuries. In 81 B.C., his work completed, Sulla stunned Rome and the ancient world (with very few other examples even in modern times) by resigning his near-absolute powers as dictator of Rome. He had done all he could to empower the Senate, restructure a more efficient government and court system, and restore order and constitutional government in Rome.

In retirement, Sulla lives a life of dissipation, conducting wild parties and entertaining his theatrical friends, living up to his added cognomen (surname) Felix. Sulla seldom intervenes in politics. In poor health and aged beyond his years, Sulla dies at his country villa near Puteoli. Just before his death in 78 B.C., Sulla completed his memoirs, which are now lost but were used by ancient writers, including Plutarch in writing his Lives. Sulla wrote his own epitaph, “No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full.”(2) McCullough shortened this line: “No better friend. No worse enemy.”(3)

The war in Spain conducted by Metellus Pius and Pompey the Great against the exploits of the renegade guerrilla fighter Quintus Sertorius is dramatically and accurately recounted, as is the famous story of young Julius Caesar and the Cilician pirates.(4)

After Sulla’s death, his lieutenants Crassus and Pompey vie for power. The Senate — as always suspicious of military strongmen who may threaten the Republic and imitate Sulla’s successful march on Rome — antagonizes both men. The two men are drawn together by that antagonism and a young Julius Caesar, astutely recognizing he would need both men in the future and already machinating for power behind the scenes, becomes peacemaker between Pompey and Crassus and forges their political partnership. The book ends with the highly successful first joint consulship between the naive Pompey and the avaricious Crassus (70-69 B.C.). The boon, prosperity and halcyon days of their joint consulship, presage the lull before the storm.

This book is once again an exhilarating read but politically savvy readers must beware! My general criticisms, as related in my previous reviews of her earlier works — The First Man in Rome(5) and The Grass Crown(6) — unfortunately remain applicable. Once again, I opine this third historic novel in the series would have been a classic masterpiece had not the author continued her idolatrous admiration for some of her main Populares (i.e., “men of the people”) faction protagonists to the detriment of other worthy but historic figures, who happen to belong to the conservative faction, the Optimates (i.e., “the best”), including politicians, generals, and statesmen, who in the context of history deserve a more unbiased and balanced treatment in her novels. This is particularly so given that the author continues to claim historic veracity as she wrote in her glossary, “In this Roman series I have severely limited my novelist’s imagination, and do not allow it to contradict history.”(7) I have suggested in my first review that when she decided not to use the terms Populares and Optimates in her books, she is at least making an effort not to make too obvious her irrepressible political bias in these historic novels.(5-6)

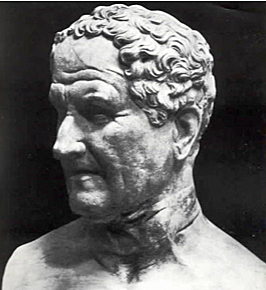

McCullough heaps adulatory praise on the fictitious character, Lucius Decumius, who is a neighbor of Aurelia (Julius Caesar’s mother) in the Subura. The unsavory character is a neighborhood godfather, a paid assassin, and guardian of the Brotherhood of the Crossroads. Decumius becomes Aurelia’s unlikely friend and bodyguard in the poorer neighborhood where the family of Julius Caesar resides. Caesar, even in his twenties, still calls him “dad!” Decumius becomes throughout all three of her first novels a likable fellow and a minor hero.(7) And yet McCullough continues to disparage members of the old conservative families, particularly the Caecilii Metelli and the Pompeii clans, whom she assails with a vengeance, sometimes with a veneer of humor, at other times with unadulterated venom. The examples are legion: Metellus Pius, in truth an accomplished general, officious Pontifex Maximus and perhaps the kindest Roman of his generation, is portrayed as a stutterer and referred to as “the Piglet,” after a fictitious incident relating to his father. His kinsman, Metellus Caprarius, is simply called “the goat”; Pompey Strabo, is assailed without mercy as “The Butcher” and imparted with horrible sanitation and unhygienic practices within his army, resulting in an epidemic that causes his own death. In comparison young Julius Caesar is a “cleanliness fanatic,” whose women must be checked by his slave before he touches them, and has all body hair painfully removed by a manicurist to prevent body lice.(8) Pompey the Great is repeatedly referred to as “Kid Butcher,” tainted with the sin of his father and also, perhaps, because of the illegal execution of the consul Carbo, even though a more merciful general than Pompey would be difficult to find, judging by the standards of the age.

McCullough’s Pompey is a conniving and unmerciful betrayer enamored of (and caring only) for himself, a partial caricature of the man, not the whole Pompey of Plutarch or history.(9) She claims, “he has the temerity to call himself magnus.”(10) In truth, Pompey was given that title by Sulla, and as Plutarch notes, Pompey did not use the title officially until years later.

McCullough has done her research though, and there is usually some level of truth behind the epithets or defamations. The problem is that they mostly occur on one side of the aisle, denigrating Roman generals or magistrates of a conservative political persuasion. Consider a typical contrast: The junior conservative (pro-Sullan) consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus gives a “diatribe and cries angrily” to the Senate, but his senior partner, the unstable, demagogic, and later renegade, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, speaks “firmly to an attentive Senate.”(11) The accomplished Roman general Licinius Lucullus is accused of being attracted to underage girls and even partaking in debauchery at Sulla’s villa during the strong man’s retirement. There is no evidence of this perversion on the part of Lucullus. During his own retirement, after leaving politics, Lucullus became and was famous for his sumptuous dinners giving rise to the term Lucullan feast, but debauchery was never noted to my knowledge. Plutarch certainly does not mention it.(12)

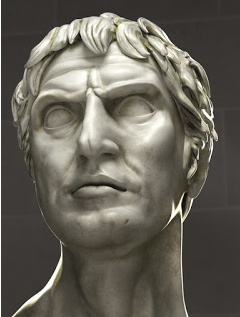

Of the Roman patricians, McCullough, it seems, has only praise and decorous words for those families, which have bred powerful Populares politicians or a troublesome and iconoclastic demagogues — e.g., the Marii, the Julii, the Claudii and the Aemilii Lepidi. Of young Sulla, we have already said a mouthful in my review of The First Man of Rome.(5) Suffice to say, at various times the Sulla of history also became almost distorted, not only imbued of evil but also disillusioned and mostly unhappy, not the Sulla who always believed that Fortune smiled on him and cognominated himself Felix. In this book, Sulla is depicted as an old man full of resentment, more accursed than propitiated by Fortune — even on his day of triumph after the Battle of the Colline Gate.(13) Even the sketch of Sulla in his old age (based on an authentic bust of him) is utterly unrecognizable. McCullough’s sketch evinces a diabolically, rancorous, and ridiculously ugly old man (Sulla was only 60 when he died); the authentic bust is much more charitable and although still revealing an elder man, there is firmness and resolution in this real Sulla. And yet to be completely fair, I must admit McCullough surprised me, when she weaved a remarkable narrative of Sulla’s work as dictator and master of Rome. Suddenly we find in Sulla a Roman patriot and a statesman — a man who did care for the preservation of the Republic and his dignitas, beyond everything else. McCullough paints an almost pretty picture and ends up nearly completely rehabilitating the man — that is until his abdication and drunken departure from Rome and in his subsequent life of debauchery and dissolution in retirement! Gaius Marius was given a medical excuse (i.e., insane “and no longer himself”) for his murderous rampage; Sulla’s personal sins were not given the benefit of the doubt in the novels but were magnified to excess.(5-6) But let’s face it from the author’s point of view: Marius, after all, was a popular leader, and “an Italian hayseed with no Greek”; Sulla was on Optimate leader and a Roman patrician.

Besides the personal political bias, a fundamental and underlying theme to the first three novels is that Rome was or had become a bloated mercantile aristocracy imbued with official and financial corruption by her magistrates and her well-to-do business class, the knights (i.e., Equites). The problem is compounded by Rome having become a land-based, depopulated empire in which the small farmers have joined the legions and lost their land. Latifundia run by slaves and absentee landlords is rampant, as is the greed of the even more corrupted Senatorial class, who without calling them so, are by far Optimates, the boni (“the good men”), thus reactionaries and ultraconservatives, who want to preserve the status quo of the Republic (i.e., mos maiorium) at all cost. Thus the road is being paved for the justification of Caesar’s future actions, the casting of the die and his fateful crossing of the Rubicon, to bring about the death knell of the Republic.

The Roman Senate had been the rock of stability that for five centuries had led Rome through innumerable crises — including the invasion and sack of Rome by the Gauls in 390 B.C.; the Italian wars; the Punic Wars; the campaigns to expulse King Pyrrhus of Epirus from Italy (Pyrrhus’ advisor and envoy described the Roman Senate as “an assemblage of kings” and exhorted him to sue for peace); the wars against Macedonia; the campaign against the Seleucid King Antiochus the Great; not to mention slave revolts and more mundane problems such as grain shortages, financial crises, etc. Yet, McCullough has nothing but scorn and reprobation for that august advisory body and venerated institution with tremendous auctoritas in Rome. In the thoughts of Pompey the Great, who ultimately dies for Republican rule and the Senatorial cause after his return from the arduous campaign in Spain, “The Senate could be bought as easily as cakes from the bakery, and its inertia so monumental that it could hardly move out of the way of its own downfall.”(14)

We are led to believe the corruption of Roman officials — i.e., embezzlement, bribery, and extortion by incompetent generals, quaestors, praetors, even consuls and proconsuls and the whole Senatorial class of the Republic — knew no bounds, and yet these were the same men who were tough as nails, relentlessly competitive, and willing to spend fortunes for the cursus honorum (advancement in political life in the pursuit of auctoritas), brave to the core and willing to lay down their lives for Rome at any time and to preserve their dignitas at all costs. Surely there was corruption and venality in the upper and ruling classes but not to the degree McCullough suggests. Otherwise how does one explain five centuries of incredible expansion and military and political brilliance unprecedented in history? One wonders how the Roman Republic grew so rapidly into a land and maritime empire that conquered the western world; kept the vast barbarian hordes at bay; created a civilization with incredible marvels of engineering, bridges, roads, sewers, aqueducts, monumental architectural wonders; and debated and promulgated magnificent laws. And then transferred these achievements to an Empire that continued to prosper for centuries, at Rome and later at Constantinople. The Roman Empire continued to marvel at the earlier Republic and thus preserved at least in appearance, if not in substance, the semblance of Republican governance with figure head senators and consuls — and the preservation of the rule of law. In our own day in the United States we have a Senate derived from its Roman namesake; our Senators debate, argue, vote, and “filibuster” like the Romans; lawyers litigate and prosecutors prosecute like their ancient Roman counterparts, and we are not immune to bribery, embezzlement or extortion, although today’s methods may be more refined.(15-16) I wholeheartedly recommend this splendid book with the aforementioned caveats.

Read Dr. Faria’s review of the previous installment or the next installment of McCullough’s “Masters of Rome” series.

References

1) McCullough C. Fortune’s Favorite. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 1993, p. 865.

2) Durant W. The Story of Civilization, Volume 3, Caesar and Christ. Simon and Schuster, Inc., New York, NY, 1980.

3) McCullough. Op. cit., p. 435.

4) Ibid., p. 620-638.

5) Faria MA. The First Man in Rome — The Apotheosis of Gaius Marius. A Book Review of The First Man in Rome (1990) by Colleen McCullough. Hacienda Publishing, Inc., Macon, GA, June 4, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-first-man-in-rome-the-apotheosis-of-gaius-marius.

6) Faria MA. The Grass Crown — Ancient Rome: Marius vs Sulla and the Marsian Wars! A Book Review of The Grass Crown (1991) by Colleen McCullough. Hacienda Publishing, Inc., Macon, GA, June 6, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-grass-crown-ancient-rome-marius-vs-sulla-and-the-marsian-wars.

7) McCullough. “Masters of Rome” Box Set. https://bookreadfree.com/252094/6223195. For the fictional character Decumius, see McCullough, Op. cit., p. 92-93.

8) Ibid., p. 440.

9) Plutarch. Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. Translated by John Dryden, Modern Library, Random House, New York, NY, p. 739-801.

10) McCullough. Op. cit., p. 492.

11) Ibid., p. 482-489.

12) Plutarch. Op. cit., p. 592-626.

13) Ibid., p. 162.

14. McCullough. Op cit., p. 723.

15. Faria MA. Faria: The Electoral College in the U.S. Constitutional Republic. GOPUSA.com, August 24, 2011. Revised article available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/faria-the-electoral-college-in-the-u-s-constitutional-republic.

16. Faria MA. The Political Spectrum (Part II) — The Center: A Democracy or a Constitutional Republic? Hacienda Publishing, Inc., Macon, GA, August 24, 2011. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-political-spectrum-part-ii-the-center-a-democracy-or-a-constitutional-republic.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI), and an Ex-member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2002-05; former Editor-in-chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002). Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution:Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 8, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/fortunes-favorites-in-ancient-rome–sulla-pompey-crassus-and-caesar.

(Fortune’s Favorites by Colleen McCullough (1993). William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 878 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s Fortune’s Favorites. A shortened and unillustrated version of this article appeared also in Amazon.com book reviews.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar”

The history of civilization began with marauding tribes raiding villages, killing men or enslaving them, raping or capturing women and children for slavery. Crops stolen. Burning and pillaging of villages and rural communities, where only the few resourceful survived, no roads, no bridges, no sanitation, no hygiene, no potable water except streams. The Greeks and Romans changed that in Europe and brought civilization—arches, concrete, bridges, vaults, domes, aqueducts, stone buildings with courtyards, baths, marble columns, surplus food, laws, philosophy, art, etc. The Romans were surrounded by barbarian tribes—Goths, Alemanni, Celts, Bulgars, Scythians, Turks, Parthians, etc.—who threatened the Roman frontier on all fronts and coveted the empire. Yes, the Romans might have been cruel but they had to be in order to survive and protect their borders and civilization. In turn, they conquered and eventually expanded to leave us an enduring legacy. The Germans came to the attention of the Romans after they crossed the Rhine to conquer the Gauls, who asked the Romans for assistance….Yes, the Romans were cruel but they had to be tough in order to protect their empire and to rule Europe and the Mediterranean for nearly two millennia! If there had been no Romans—there would be no surviving aesthetic Greek culture, Western civilization, or Christianity. The nearest civilizations to the Graeco-Romans were the Persians, Parthians, and Sassanians. And if these eastern potentates had won, we would be speaking Arabic or Farsi today, part of the Arab or Iranian world—Muslims. How is your Arabic? But since the Romans are part of Western Civilization, they are vilified in the popular culture and academia that would rather us be communist or anything other than American and part of Western civilization. Think about it when you hear our Graeco-Roman heritage slandered by those indoctrinated by the mainstream liberal media and the popular culture.—Dr. Miguel A. Faria, whose next book in preparation is The Roman Republic, History, Myths, Politics, and Novelistic Historiography (2025) by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK