- Articles

The First Man in Rome — The Apotheosis of Gaius Marius!

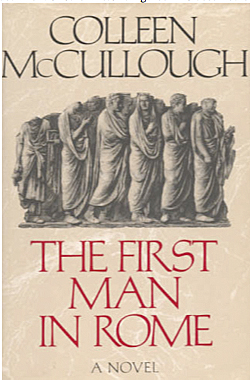

This is a wonderful introduction to the “Masters of Rome” series of historic novels by famed author Colleen McCullough. The first tome in this series, The First Man in Rome, at 896 pages, including magnificent maps, glossary, even sketch portraits of many of the main characters, is incredibly well-researched. Crisp writing, eloquent prose, exhilarating reading, spellbinding plots and intrigue — are all parts and parcel of this literary, unfolding, historic drama. The historic novel would have been a complete masterpiece had not the author fallen head over heels for the main protagonist, Gaius Marius, to the detriment of other historic figures who deserved better, particularly when the author boasted of historic veracity. Indeed, McCullough’s scholarship is outstanding, and her literary abilities certain; the problem lies elsewhere, apparently her politics and her prejudicial bias for the Populares faction at the expense of the Optimates and the historical veracity she claimed.

Thus, to cover her political leanings, the author does not use those terms at all in her novel, as she “does not want to give the impression that there were formal political parties.” The reality is she does not want to make her liberal leanings too obvious to her readership. Had she used those helpful and historic political terms, it would have made it too obvious that at least in her mind, with few exceptions, all the popular leaders and political demagogues pandering to the mob were the good guys with nobility of purpose and good intentions (e.g., not only Marius, but Saturninus and later Sulpicius, Cinna, and Carbo), while the Optimate leaders and the members of the old conservative-leaning families, those upholding the mos maiorum (i.e.,”the established order of things” and the “established customs of ancestors”) were, almost uniformly, the bad guys. For example Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus, actually a great and distinguished Roman, was turned into an incompetent general and undeservingly nicknamed “Piggle-wiggle” because in a fictional account Gaius Marius, McCullough’s hero, throws Numidicus down on a pigsty in Numantia to the delight of young Jugurtha and Rutilius Rufus. His son Metellus Pius, also a distinguished Politician and war hero, is made to stutter and called derisively “the Piglet.” The Caepios, with some truth, are severely and umnmercifully turned into despicable villains. McCullough dwells and relishes describing the low living, dissipated adolescence of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who is turned into a Dr. Jekyl and (mostly) a Mr. Hyde, a homosexual poisoner and serial killer with misogynistic tendencies and prone to pathological violence, which of course makes tantalizing reading but distorts history. In book two of this series, The Grass Crown, Sulla is even made to kill by poisoning a member of his party and mentor, Caecilius Metelus Numidicus, enraged in a completely fictional and implausible scenario! In fact, Sulla in his memoirs, which are unfortunately no longer extant but read and quoted by Plutarch, wrote that “his concord with Metellus, his equal, and his connections by marriage [were] a piece of preternatural felicity.”(1)

Returning to Gaius Marius, suffice to say that had he been a fictional character, McCullough would have been free to put him in Mount Olympus, but being a real historic figure with warts, wrinkles, and major flaws in his character — no better and in some ways worse than those of Lucius Cornelius Sulla — the revisionism in this fictional but historic novel raises eyebrows in some of us aware of Roman history and “qualified to judge.”

In this book with some historic evidence, Gaius Marius, the New Man (i.e., the first in his family to reach consular status) is held suspect and disliked by the old aristocracy not only because of his humble origin, “an Italian hayseed with no Greek,” but also because of his opposition to the Senate, his involvement with the People’s and the Plebeian assemblies, where he usually obtained what he wanted politically (i.e., appointments and reappointments as consul and given repeated military commands), as well as his iconoclastic politics. Thus McCullough sets out to reconstruct Marius’ persona, to invent a more likable and agreeable character, albeit a less historic figure. McCullough transforms Gaius Marius, the man, into an accomplished orator, political thinker, almost a philosopher, the best of the Romans, graceful and congenial, despite his military manner. He is fluent in Ionian Greek but timidity prevents him from displaying his learning. Even Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, his political enemy, is made to admit, although rather implausibly, “Marius has a wonderfully sharp brain between his ears,”(2) and calls him the “Arpinate Fox” for his political acumen,(3) when in reality the historic record (not to mention Plutarch, whom the author herself has used in her research) gives us a very different and unflattering picture of the hero.

Plutarch writes: “[Marius] a man altogether ignorant of civil life and ordinary politics, he received all his advancement from war.”(4) Moreover, opines Plutarch, “[Marius is] inferior to others in agreeableness of conversation and the arts of political life, a mere tool and implement of war.”(5)

Novelistic license has its limits for those of us who, as the author puts it, “are qualified to judge.” And yet, McCullough has written a magnificent historic novel, and indeed most of what she has written with so much research is well within her purview of literary creativity and within the boundaries of factual history.

Take for instance the magnificent creation of Julilla, as the second daughter of Gaius Julius Caesar (grandfather of Julius Caesar), who in the story becomes Sulla’s first wife — thus binding Marius and Sulla to the Julii clan, as well as making them brothers-in-law and relations to the future Julius Caesar. Indeed in this novel, not unreasonably, Marius and Sulla are close confidantes and collaborating friends, militarily and politically, longer than we expect from the historic record. The plausible family interconnections and relations are in fact a stroke of literary and novelistic historic genius, given the fact that Sulla’s first wife was a “Julia,” and Sulla truly served as second-in-command to Gaius Marius, both during the war with Jugurtha in Numidia and against the Germanic Teutones and Cimbri. Likewise, the informative and witty correspondence of the consular Publius Rutilius Rufus and various characters, particularly his close friend Marius, is outstanding, reminding us of the use of similar literary correspondence in Gore Vidal’s masterpiece, Julian.

For the sake of intrigue and dramatic tension, I also find no fault in assigning Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s failure in his first campaign for the position of Praetor to the opposition of the powerful Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, Princeps Senatus. Why? Because of sexual matters and intrigue. The reasons chronicled were his lack of money and not having provided games for the mob as was expected of the candidates. To further enhance her novelistic plot, Caecilia Metella Dalmatica, Scaurus’ wife, had become infatuated with Sulla, embarrassing the influential and powerful Scaurus and threatening his dignitas! This makes for a more intriguing plot.

McCullough’s narrative is spellbinding: The 20-year migration of the Cimbri and Teutones to Italy from the Jutland peninsula and northern Germany, as related by the “spy” Sulla to Marius, is marvelously reconstructed. The events leading to and stemming from, as well as the battles of Arausio, in which 80,000 Romans were decimated; Aquae Sextiae, where the Teutones were obliterated in 101 B.C.; and finally Vercellae later that year, where the Cimbri armies were completely destroyed, are magnificently described.

Towards the end of this first book, Mccullough describes the insurrection of the odius Tribune of the Plebs, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, favorite of the mobs, and his sidekick Gaius Servilius Glaucia who attempted the overthrow of the Republic with violence and mayhem. McCullough enhances their performance by writing for Saturninus a marvelous piece of oratory pandering to the mob. Nevertheless, Marius, who is forced to choose, makes the political decision to side with Scaurus and the Senate, and in the hands of Sulla enforces the Senate’s ultimate decree to protect the state — senatus consultum de republica defendenda. Saturninus, Glaucia and their followers, Marius’ former friends and political allies, are put to death. Had Marius retired at this point in his life to rest on his laurels — the conqueror of the Teutones and Cimbri and the saviour of Rome — his well-deserved historical reputation would have been unblemished. But that was not to be. Marius’ ambition to gain the seventh consulship and be the greatest Roman, and his consuming, iniquitous obsession to destroy the Senatorial class (to which he already belonged), would destroy him and marr his life.

Aemilius Scaurus is another main character in this novel, and we are surprised to find he is perhaps the only conservative Roman politician whose reputation is enhanced. Indeed we learn to love him in this historic novel. Most other Roman conservative politicians are disparaged and belittled without mercy. And this political historic bias is a second (and closely related) detraction, the fictional apotheosis of Gaius Marius, in this otherwise spellbinding historic novel. Needless to say, those readers attuned only to historic melodrama, but not necessarily “qualified to judge” in the historic arena and oblivious to historic reality and political sentiment, will find no fault with this book and may even misconstrue my “parochial” criticism as undeserved. But the reader is invited to read the magnificent Plutarch, still highly readable, to ascertain my criticisms. These valid caveats still do not detract me from recommending this book (4 out of 5 stars). I have already finished her second book, The Grass Crown, and I am presently reading the third book in this series, Fortune’s Favorites. I plan to continue to review these books for my readers and for those interested in ascertaining fact from fiction in these fascinating historic novels.

References

1) Plutarch, Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. Translated by John Dryden. Modern Library, Random House, New York, NY, p. 549.

2) McCullough C. The First Man in Rome. 1990. William Morrow and Company, Inc., p. 695.

3) Ibid., p. 718.

4) Plutarch, Lives. op cit., p. 513.

5) Ibid., p. 514.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI), and an Ex-member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2002-05; former Editor-in-chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002). Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. The First Man in Rome — The Apotheosis of Gaius Marius! HaciendaPublishing.com, June 4, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-first-man-in-rome–the-apotheosis-of-gaius-marius.

(The First Man in Rome by Colleen McCullough (1990). William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 896 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive book review for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s The First Man in Rome. An unillustrated, shortened version of this book review was published in Amazon.com on June 3, 2013.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

4 thoughts on “The First Man in Rome — The Apotheosis of Gaius Marius!”

Battle of Arausio, Oct 6, 105 BC by Jesus Vico andMaria Ollero

The Battle of Arausio took place on October 6, 105 BC in the midst of the Cimbrian Wars, 113-101BC. This battle was a confrontation between the Roman Republican legions, led by the consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus and the proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio, and the Germanic tribes (mainly the Cimbri, Teutoni and Ambri) led by the Cimbri King Boiorix and Teuton King Teutobod. It took place between the village of Arausio (in today’s Vaucluse) and the River Rhodanos (Rhône).

As a consequence of the division of the Roman forces in two armies, due to the bad relations that existed between the two leaders, the battle was an utter catastrophe for the Republic.

In 111 BC, the Ambri and the Cimbri arrived in the southwest of Germania Magna, where the Teutoni and Tigurini joined them. They were looking for a land to settle in a long journey across the continent.

In 108 BC, the Roman Senate rejected the Cimbrian demand for new lands to settle. This event triggered their attack on the consul Marcus Junius Silanus, who was defeated. A year later, the migrants started the invasion of Gaul, including the Roman province of Narbonensis (Narbonne). The legions tried to defend Burdigala (Bordeaux) but were once again defeated.

According to the data and estimates, the Republican army was formed by around 66,000 soldiers in 107 BC. This was about eight legions and a supplementum of another 5,000 men.

The Germanic migrants added (according to Plutarch) about 300,000 warriors, followed by a much bigger horde of women and children.

Although being remembered as as one of the greatest major military disasters in the history of Rome, little is known of the Battle of Arausio due to lack of existing detailed records. This leaves room for a lot of speculation to fill the voids.

What is known is that the proconsul Caepio, a patrician, was reluctant to receive orders from Gnaeus Maellius Maximus, who had a higher rank, but was a commoner. Both commanders built their camps on opposite sides of the River Rhodanos, more obsessed with their internal feud than engaging the enemy.

The battle began with the legate Marcus Aurelius Scaurus leading a detachment consular cavalry to scout the area of which the Germanic armies quickly encircled.

The Germanic officers convened a council and offered Scaurus the possibility of release. Scaurus, a man of great honor, said it would be an outrage to flee while his troops were massacred. Scaurus also warned the Cimbri king that if he tried to cross the Alps towards Rome all of his people would die. Scaurus was summarily executed for his impudence.

This execution alarmed the consul, and he wrote a letter to the proconsul asking to join forces, but Caepio refused, claiming he had to protect his own territory. Nevertheless he accepted to cross the River Rhodanos and set his camp between the migrant army and the troops of Maellius. He wanted to be the first to fight, so that he would ensure his glorification in case of victory.

Caepio soon learnt that Maellius was trying to negotiate with the Germanics, and this enraged him and augmented the feud that was already going on between them.

Soon after, the migrants sent emissaries to ask for land to settle and wheat to seed, but the proconsul refused and they were almost executed. Caepio launched an attack against the migrant encampment, but was easily defeated, and the survivors fled to Maellius.

Both Roman camps where close enough though, but with Caepio refusing to join Maellius, they were unable to help. It is possible that the consul didn´t have time to react, and the crowd of fugitives brought confusion to his ranks. The Germanics, empowered by their victory, attacked the second Republican force.

The Romans were cornered by the Germanics in the river, and many drowned. Both camps were sacked, and both Maellius and Caepio were ultimately defeated.

But the Republican Romans do not sit well with defeats, and like the British, when the Tories were in power in Victorian England, do not leave their defeats go unavenged! As I wrote in reviewing McCullough’s book: “The 20-year migration of the Cimbri and Teutones to Italy from the Jutland peninsula and northern Germany, as related by the “spy” Sulla to Marius, is marvelously reconstructed. The events leading to and stemming from, as well as the battles of Arausio, in which up to 80,000 Romans were decimated. [105 BC]” But then came the avenging long arm of Rome: Aquae Sextiae, where the Teutones were obliterated in 101 B.C.; and then Vercellae later that year, where the Cimbri armies were completely destroyed!

You have heard of the expression, to “draw a line in the sand.” Well here is the story: It goes back to the same King Antiochus IV and the Roman consul Gaius Popillius Laenas. In 168 B.C., the Seleucid King was about to invade Alexandria and Ptolemaic (Egyptian) territory with a large army. The Ptolemaic kingdom was a friend of Rome and you don’t mess with Rome’s friends. Both Livy and Polybius tell the story. In any event, the Roman envoy Laenas with a few other Roman dignitaries approached by foot to the frontier, drew a line or a circle around King Antiochus, and handing him a note from the Roman Senate and the Roman People (SPQR), warned him about entering Egyptian (Ptolemaic territory, a nation friendly to Rome) Laenas told him not to move out of the circle or cross the line, until he had considered the consequences. Antiochus Epiphanes hesitated momentarily but then immediately withdraw his army and returned to Syria. The power of Rome was so great and feared that a Roman envoy without an army was enough to deter a powerful king with a large body of troops from invading another nation—just by drawing a line in the sand! Our Senate was fashioned after the Roman Senate but, alas, the caliber of the occupants is not the same as in the time of the Roman Republic! 😎

The history of civilization began with marauding tribes raiding villages, killing men or enslaving them, raping or capturing women and children for slavery. Crops stolen. Burning and pillaging of villages and rural communities, where only the few resourceful survived, no roads, no bridges, no sanitation, no hygiene, no potable water except streams. The Greeks and Romans changed that in Europe and brought civilization—arches, concrete, bridges, vaults, domes, aqueducts, stone buildings with courtyards, baths, marble columns, surplus food, laws, philosophy, art, etc. The Romans were surrounded by barbarian tribes—Goths, Alemanni, Celts, Bulgars, Scythians, Turks, Parthians, etc.—who threatened the Roman frontier on all fronts and coveted the empire. Yes, the Romans might have been cruel but they had to be in order to survive and protect their borders and civilization. In turn, they conquered and eventually expanded to leave us an enduring legacy. The Germans came to the attention of the Romans after they crossed the Rhine to conquer the Gauls, who asked the Romans for assistance….Yes, the Romans were cruel but they had to be tough in order to protect their empire and to rule Europe and the Mediterranean for nearly two millennia! If there had been no Romans—there would be no surviving aesthetic Greek culture, Western civilization, or Christianity. The nearest civilizations to the Graeco-Romans were the Persians, Parthians, and Sassanians. And if these eastern potentates had won, we would be speaking Arabic or Farsi today, part of the Arab or Iranian world—Muslims. How is your Arabic? But since the Romans are part of Western Civilization, they are vilified in the popular culture and academia that would rather us be communist or anything other than American and part of Western civilization. Think about it when you hear our Graeco-Roman heritage slandered by those indoctrinated by the mainstream liberal media and the popular culture.—Dr. Miguel A. Faria, whose next book in preparation is The Roman Republic, History, Myths, Politics, and Novelistic Historiography (2025) by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK