- Articles

High Noon at the Cold War: The West Faces Down an Old Foe by Douglas P. Harden

The international system is one of danger and uncertainty, a lack of order and constant instability heighten the propensity for violence in the international system. Recent years have provided American leadership with the task of confronting numerous problems on the international scene, among them: a rising economy in China ready to overtake that of the United States, a nuclear North Korea, a nuclear Iran, Russian expansion in Ukraine, and human rights atrocities in Syria, to name a few.

United States foreign policy must become optimal in dealing with the threats effectively, but it must also be efficient in proposing and providing solutions to these problems. The issues are complex, and policy development and implementation are equally as difficult with multiple variables involved and no real assurance of certainty regardless of the policy choice.

The questions that now confront the White House are related to states and their political, military, social, and economic power. A nuclear North Korea would shift the balance of power in the Korean peninsula, a nuclear Iran would threaten Israel’s sovereignty, the growing Chinese economy has already outperformed the U.S. economy in some measures, and the propensity for Vladimir Putin to continue to annex land in an attempt to restore the Russian empire looms as an ever-present possibility.

During the Cold War, our defense posture and foreign policy became intertwined. Many states presented significant geopolitical threats to the United States, and our foreign policy approach was that we had to oppose communism where it expanded and invaded other friendly nations, such as Korea and Vietnam. We also fought proxy wars throughout the Third World in an effort to maintain regional influence and stability.

Now, we advance to the crux of the Cold War – the Soviet Union and the United States – the world’s two superpowers.

The problem with communism in the 20th century was not merely its simple existence in Russia and the Eastern Bloc, it is in its political aims as an ideology, which is that after this formation, communism encourages violence and even predicts the worldwide revolution of the proletariat and the eventual domination over all people on the earth – a one-world communist-socialist – Soviet state. Communism in Engels and Marx’s sense advocates the use of violence throughout the world to establish political legitimacy for all communist states. The spread of political fervor by way of violence and through force was of concern to the United States after World War II. While U.S. doctrine would be redefined as the years progressed, everyone in the U.S. foreign policy establishment agreed that communism was not safe for the world or the United States, if it could be eliminated this would be the stated goal, but could it be eliminated without firing a shot?

Would the Evil Empire fold under political and spiritual pressure or would it take thousands of American lives to see its end? Would it require what the United States did to end World War II or could it end without a shot being fired? Would it come to armed conflicts like those in Korea and Vietnam again? A stalemate or “Peace with Honor”? Would Americans be willing to sacrifice thousands of their sons and daughters?

The end of the Cold War was a result of many factors: world events, economics, and perhaps most notably the nature of inefficiency. The most important answer which we see now, some twenty-five years later is one that is still relevant today – wars may be fought on battlefields with guns and bombs, but wars, or rather superior political philosophies and ideas, are won in the hearts and minds of people. President Ronald Reagan, known as the “Great Communicator,” didn’t think he was a great communicator, however, he tried to communicate great things – and he did. Ideas like peace and freedom are still relatively new ideas in the history of the world.

Wars can be waged and won with armies, but victories can also be attained with ideas. The world bore witness to this at the end of the Cold War. All government leaders should consider the use and implementation of political subversion as a real, effective, and relevant foreign policy tool. Let us step back in time and see things from a historical vantage point:

American foreign policy can be viewed through two primary lens as one works to understand the historical ebb and flow of our foreign policy and the goals of this policy as it relates to dealing with other countries and threats throughout the world. The most recent lens would be the post-September 11th world in which the United States had been engaged for twenty years, combating transnational terrorism in Afghanistan and around the globe and mitigating the threat of sub-state actors – in one particular sense: terrorists and the phenomena of terrorism.

The first lens is the Cold War foreign policy of the United States that for more than forty-five years worked to fight the Soviet Union and Soviet satellite states on several fronts: political, diplomatic, monetary, cultural, ideological, and the like. From the end of World War II until 1981, the United States had adopted three primary foreign policy strategies in dealing with the Soviet Union. These are: “Rollback,” “Containment,” and “Détente.”

Thanks to President Harry Truman, “Rollback,” upheld by the United Nations in Korea, would be the first major policy implementation after World War II that hoped to roll-back communist influences and preclude what would be eventual communist takeovers in Korea and Cuba; and perhaps throughout the world for that matter.

Eventually, Korea would be divided into two spheres after the Korean conflict ended in 1953. After Fidel Castro came to power in Cuba in 1959 and the United States had failed to depose him, the United States would have to contend with ongoing Soviet influence 90 miles from its shoreline. Famed diplomat George Kennan in the Truman administration would author the U.S. containment strategy that would work to contain communist states and quell communist expansion, especially in the Third World and from a policy standpoint.

Moving forward in history, the administrations of President Richard Nixon and President Gerald Ford saw a shift in U.S. policy towards détente. Détente was a strategy that wanted to ease tensions with Moscow and work to form a working partnership between the United States and the Soviet Union – a coexistence of sorts. While they did disagree politically and ideologically, détente would see that they agree to work together at least in theory, as both remained relevant on the world’s stage during the Cold War.

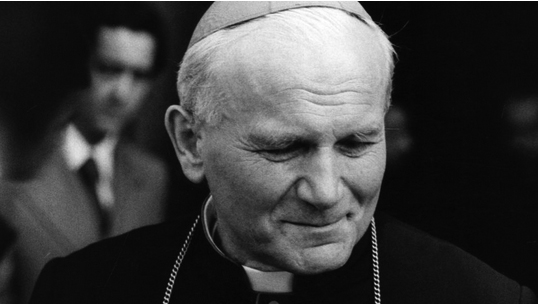

The world would come to be incredibly fortunate in the late 1970s and early 1980s, even though at the time or in years before many would have thought this to be impossible. In 1978, the Bishop of Krakow, Poland, Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła, would be elected in the Papal Conclave to become Pope. The world would come to know him as Pope John Paul II. This native of Poland would transcend the Catholic Church and Europe in his twenty-seven-year pontificate. It had only been a few years earlier that no one, perhaps not even he, would have guessed that he would rise to become Pope. After all, as a young man in Poland, he had been an actor before being ordained as a priest.

On the other side of the Atlantic, another leader, who at one time had been deemed “too old” and “too conservative” to be Governor of California much less President of the United States, was waiting patiently for America to ripen itself to hear his conservative message. During the Carter administration, inflation had gripped the American economy, the hostage crisis in Iran appeared to have no end in sight, and a “malaise” had begun to permeate American society. The man, who had served as the General Electric spokesman and who had been a B-list actor, was preparing to secure the Republican nomination for President and he would eventually become the 40th President of the United States. We had seen lawyers, soldiers, and farmers aplenty, but never an actor.

Ronald Reagan took the Oath of Office on January 20, 1981, and moved American foreign policy into a new realm, away from the previous strategies and toward one that would have a spiritual alignment to it. Communist philosophies espoused in works such as The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital are critical of faith and religion, private property, free markets, and capitalism. Soviet leaders would see firsthand in the years to come just how powerful of a force faith and religion would be.

As President Reagan took office, he wanted a new policy approach to deal with the Soviet Union. He also noted that every American president to date had adopted a policy of some sort of “not losing.” Reagan wanted to play “to win.” Much of rollback, containment, and détente would be shelved in favor of a “zero-option” strategy and a confluence of religious, ideological, and political rhetoric, pressure, diplomacy and tact, coupled with political subversion to isolate and undermine the Soviet Union and the expansion of communism. President Reagan made a speech early in his administration to a group of evangelical Christian ministers and religious leaders in which he stated that the Soviet Union was an “evil empire.” The New York Times was quick to chide the President and many at the White House were unsure as to how this would be received by the Kremlin. Reagan was undeterred however in his keystone anti-communist approach.

Meanwhile, Poland, a country that had been occupied by the Russian Army during World War II and under Soviet influence since the end of the war, was in many regards a communist state and a satellite state of the Soviet Union. Warsaw was a beacon of Russian power in Europe. The country would be reinvigorated however in 1978 with Cardinal Wojtyła’s election to the Papacy. As nationalism and religious fervor spread throughout Poland, the Pope would speak to almost a half million people in 1979 in Warsaw. Discouraging armed, violent rebellion, the Pope called for an “alternative Poland” which would consist of social institutions that were independent of and non-dependent upon the Communist Party. The Polish United Workers’ Party was the dominant political party in Poland, however, in 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared martial law in an attempt to quell the political uprising and the new independent trade union known as Solidarity that had formed in the Polish United Workers’ Party.

Led by Lech Walesa, Solidarity, the new Polish worker’s movement, had nine million members by the end of 1981, many of whom were Catholic. For much of the decade, Solidarity existed as an “underground” organization, much like the French Resistance in World War II that worked to undermine German influence and German political power in France. When President Reagan took office in 1981, he appointed William Casey to serve as the Director of Central Intelligence. Casey knew Reagan before his election as president, having served on the Reagan campaign. Casey, himself a Catholic, knew exactly what was at stake in the early 1980s when it came to defeating the Soviet Union, the breakup of the larger Soviet empire would give way to a crumbling political establishment in Moscow. Perhaps for the first time, the United States would be a major political ally to Rome.

The United States would provide monetary aid to the Solidarity Movement while President Reagan publicly supported the movement and also supported Solidarity from a policy standpoint in undermining Soviet power in Poland and Europe as well. Pope John Paul II would affirm his support for Solidarity through the broader Catholic social teaching in 1987 with his Papal Encyclical, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis. Solidarity taught peaceful civil resistance and it worked to encompass the morality of human rights past the confines of government and the central, autocratic control of Moscow. It was after all President Reagan who noted in his inaugural address the power of free people when he said, “Above all, we must realize that no arsenal or no weapon in the arsenals of the world is as formidable as the will and moral courage of free men and women. It is a weapon our adversaries in today’s world do not have.” Lech Walesa would receive the Nobel Peace Prize and serve as President of Poland in free elections after the fall of communism — a novel feat when one considers the state of Poland in 1980.

President Reagan would continue his assault on communism and the Soviet Union, eager for an arms control agreement. After the deaths of several Soviet leaders, Mikhail Gorbachev would come to power in Russia, and being much younger than his predecessors, he seemed anxious to engage the West and the United States. At the Reykjavík Summit in Iceland, both leaders on the first day of talks agreed to a proposal to dismantle and disassemble all nuclear weapons in each respective country. This was the first real proposal that would define “zero-option.” Instead of an agreement of mutual reduction, limited testing, of constricting weapon deployments in neighboring countries, both the United States and the Soviet Union had agreed in principle to de-escalate the Cold War in terms that were mutually beneficial and agreeable to both sides. President Reagan would insist that the recently proposed Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) remain a viable option for the United States while Gorbachev would want research on Strategic Defense Initiative in laboratory settings only. Both sides would leave Reykjavík without an agreement but for the first time since the Cuban Missile Crisis, an American President had stared down his Soviet counterpart — and the Russian blinked first. President Reagan did not give in to Gorbachev’s demands, and he did not make an arms control agreement just for the sake of agreeing. He did get Gorbachev to agree that human rights would be a regular topic on their agenda at each future meeting; this was major progress for the communist state of Russia. Secretary of State George Schultz would later note that this was a major turning point in U.S./Soviet relations, getting the Soviet Union to make progress on human rights issues was a tremendous accomplishment for President Reagan.

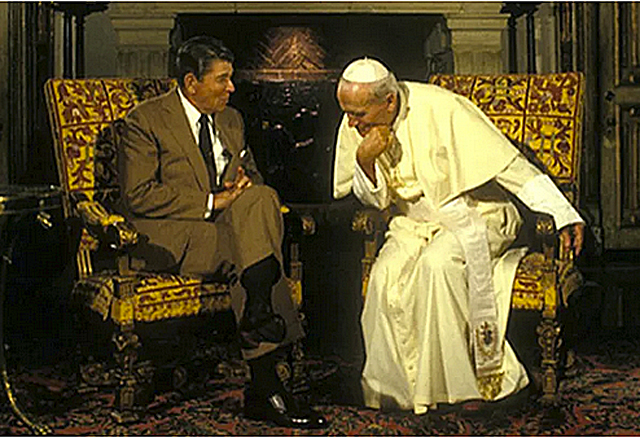

The dialogue between Washington, D.C., and Rome would reach new heights in the 1980s. President Reagan and Pope John Paul II would develop a sort of spiritual, religious, and ideological kinship and an admiration for each other. Both had been actors, both had survived assassination attempts early in their tenures, both had scorned communism since early adulthood, Reagan fighting communist sympathizers in Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s during protests and picket line crossings and the Pope since his time in Poland during Soviet occupation. In the late 1970s, both were seen as “long-shots” at best to become President of the United States and Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church.

Reagan would make one of his most well-known speeches at the Brandenburg Gate, urging Soviet leader Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall, and the policy that had been set in motion since 1981 was now moving with enough momentum that the Soviet Union would crumble. With the eventual fall of the Berlin Wall and the acknowledgment by Moscow of the independence of the Soviet socialist republics of the Soviet Union, and the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the world would witness the end of Russian communism.

Eventually, the political pressure from the United States and the West, and the spiritual and religious influence from Pope John Paul II and Rome would become too much for Moscow to bear. The Pope and President Reagan, while serving in different leadership capacities, had slain the dragon of modern-day socialism and post-World War II communism. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, it all began to fall, with the final dissolution of the Soviet Union coming in December 1991. It would all be over, without firing a shot. All the nuclear weapons that had been built in both countries since 1945 would not be used after all, and the generational belief of fighting the Russian army had now fallen by the wayside. The West and the United States had won, and they did it more so with ideas and a moral value system than they could have ever hoped to do with guns and bullets. Political subversion had turned the tide in the Cold War, undermining the communist stronghold in Warsaw and throughout Poland and proving to be too much for Moscow to contain. Gradually the innate human desire to be free triumphed over the antiquated philosophy of control and fear.

As the United States works to confront China, North Korea, Iran, and Putin’s Russia, armed conflict should always be an option of last resort. Ideas followed by wise statesmanship and effective political movements have proven to be more successful in freeing people than destructive wars in many situations. Perhaps one might find this belief naïve. Maybe it is in some ways, however, in others, perhaps it’s a radical idea – one we’ve only seen infrequently. Just ask President Reagan and Pope Saint John Paul II.

The cold warrior Ronald Reagan and Pope Saint John Paul II knew that communism could not be reformed because it is inherently flawed and Solidarity proved to be the element that was the turning point in Europe to push the waters of freedom onto the shores of eastern Europe.

Will something similar happen in countries like China, North Korea, or Cuba? Could we see powerful entrenched totalitarian regimes and governments fall? The world still has the ideas and beliefs that men can govern themselves and that men should not be bound or controlled by the state. As President Reagan told us, “Above all, we must realize that no arsenal or no weapon in the arsenals of the world is so formidable as the will and moral courage of free men and women. It is a weapon our adversaries in today’s world do not have.” It was true in 1981 and it is still true today.

Thanks to the late President Reagan and Pope Saint John Paul II, the world can now learn from their example as the 21st century continues to await such bold leadership.

Written by Douglas P. Harden

Douglas P. Harden graduated from the University of Georgia, School of Public and International Affairs in 2005 with a degree in international affairs. He is currently with the Department of Energy.

This article may be cited as: Harden DP. High Noon at the Cold War: The West Faces Down an Old Foe. HaciendaPublishing.com, June 20, 2022. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/high-noon-at-the-cold-war-the-west-faces-down-an-old-foe-by-douglas-p-harden.

Copyright ©2022 Hacienda Publishing, Inc.