- Articles

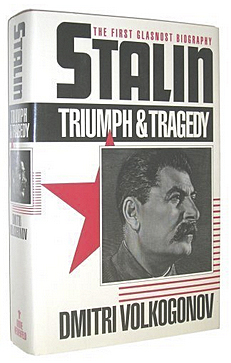

Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy by Dmitri Antonovich Volkogonov

As head of the Institute of Military History of the USSR and General of the Soviet Army, Dmitri Volkogonov had access to secret Soviet documents not available to other historians up to the time of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika.

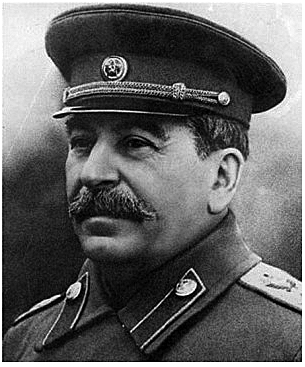

This authoritative, engaging, and instructive biography of the Red Czar of Soviet Communism, Comrade Joseph Stalin, was published in Russia in 1988, but was not translated and published in English until 1991, a pivotal year when the Russian bear stumbled bringing about the total collapse of Soviet communism.

The fact that this biography was completed and published during those years is crucial in understanding the work of General Volkogonov, and this timing allows me to add my nickel’s worth to the compilation of reviews of this magnificent and authoritative biography. I say this because one gets the impression that Volkogonov has ambivalent feelings about the ideals, utility, and worthiness of Soviet communism, which he usually refers to as socialism. His ambivalence is, at times, obvious and may be the result of political doubts and anxiety in his dual life in communist Russia.

Even by 1988 the general had not quite shed the skin of his “socialist” background. To all appearances, Volkogonov was a hard-line military man, a general in the political department. Secretly, he was a historian, researching and writing the life of crime of the Red Czar, Joseph Stalin. Would he have concluded this assessment different, if he had finished his Russian edition in 1992 or 1993, rather than 1988?

Throughout the book, Volkogonov seems to imply that had Stalin not usurped the reins of power and Lenin’s course had been followed, Soviet Communism in the USSR — as traced by Lenin and theoretically enforced after his death by a collective leadership — might have ended in a more democratic socialism, a true Russian, socialistic utopia.

At other times, Volkogonov seems to admit that even with a collective leadership, the course of Russian history might not have made a difference because Lenin, just like Stalin, had called for the pragmatic use of force and terror.

Volkogonov recalls in a footnote that after the February Revolution, the Provisional Government had convened a Constituent Assembly that would establish a constitution for the Russian people to “determine the nature of the state.” But lawful, constitutional rule never happened. After Lenin seized power, elections were held, but as the Bolsheviks received less than a quarter of the votes in the Assembly, they quickly dispersed the Assembly by force on January 18, 1918, the first and only “democratic” session.

Lenin nor Stalin wanted democracy or constitutional rule; they both wanted to eliminate the opposition at any cost and establish a “dictatorship of the proletariat” not in the image of the workers and peasants as they proclaimed, but in their own image. And yet, Volkogonov is at times, reluctant to cast Lenin and Stalin in the same collectivist, autocratic, totalitarian mold. The General insisted that events could have taken a different turn, if only Lenin’s heed had been followed.

Volkogonov asserts this possibility, despite the fact that he himself provides evidence that, except for Bukharin in the 1920s and 30s, all of the Bolsheviks, following the lead of Lenin and Stalin, including not only Stalin’s minions, Molotov, Voroshilov, and Kaganovich, but also Trotsky, Kamenev, and Zinoviev — all sanctioned the use of violence, the use of coercive state power, and the use of terror, in peacetime or wartime, to consolidate Soviet power and subdue the Russian masses in whose name they supposedly ruled!.

We learn with documentation provided in this book that it was Kamenev and Zinoviev, leading Politburo members, ironically, who orchestrated Stalin’s election to the office of General Secretary of the USSR. They erred in the belief that they could manipulate Stalin against Trotsky and that they could exercise more power through the then more influential Politburo. Simply, “they feared Trotsky more than they feared Stalin.” They would later pay with their lives for this misjudgment and become two of Stalin’s most celebrated Bolshevik victims!

Stalin’s craftiness and will power were vastly underestimated by his Bolshevik opponents. During the Party Congresses, duels over Trotsky’s call for “world revolution” versus Stalin’s state policy of “socialism in one country,” Trotsky had thought of Stalin as an “outstanding mediocrity, ” another misjudgment that eventually proved fatal to Trotsky.

Volkogonov’s engaging narrative takes us through the political purges, the meat grinding of Russian society, and the elimination of Stalin’s real or imagined opponents: the “Right deviationists,” Rykov, Tomsky, and of course, their leader, Bukharin (Lenin’s “favorite of the Party”) and the military exemplified by Marshall Tukhachevsky; the Left internationalists, Trotsky and his followers; and the vacillators, the Bolshevik duo, Kamenev and Zinoviev. Even Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD was not immune and a large number of those who executed in his name, such as G. Yagoda, N. Yezhov, and V. Abakumov, were themselves executed as the meat grinder continued.

One cannot help but be reminded of the similar happenings that took place in France a little over a century earlier. In the French Revolution Maximilien Robespierre destroyed his royalist enemies first, then the courageous Girondins, led by Madame Roland, Brissot, Vergniaud and their followers on the right; then the vicious troublemakers of the left, including the cowardly radical “enrages,” Rene Hebert (Le Pere Duchesne) and the Paris Commune leader Pierre Gaspard Chaumette; then the moderate “indulgents,” who eventually included Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, the titan of the Revolution himself.

Even Stalin’s sanguinary State Prosecutor, the odious Andrey Vyshinsky tormenting and haranguing “enemies of the people” during the secret or kangaroo trials of the great purges cannot help but elicit in the reader the sinister, bloodthirsty images of Fouquier-Tinville, the Prosecutor for the Revolutionary Tribunals during the French Revolution, acting under orders from Robespierre, just as Vyshinsky acted under orders from Stalin, administering grotesque impersonations of justice, preordained executions and the perpetuation of terror. But unlike the reign of terror of Robespierre that lasted less than two years, Stalin’s terror lasted decades, fluctuating in intensity as he saw fit during the entire period of his emerging dictatorship from approximately 1924 until the very day of his death, March 5, 1953! And his legacy of totalitarian communism lived on until 1991!

With good reason, the Girondin Deputy and orator, Pierre Vergniaud, exclaimed, “The revolution, like Saturn, devours its own children.” And so it did in Russia, and in the end, only Stalin and his loyal inner circle of henchmen (dissimulating or not) survived, Beria (briefly), Malenkov, Molotov, Kaganovich, Mikoyan, Bulganin, and Khrushchev.

While General Volkogonov describes the brutality and the crimes of the Stalin years in graphic detail, reconstructed from interviews, as well as secret documents from the archives of the Communist Party of the USSR, military records, Comintern papers, and letters — we must also keep in mind that Intelligence (NKVD) records were not available to him.

Ironically, for secret foreign intelligence and Stalin’s use of espionage and the KGB against the United States and Western Europe, we must still turn to other materials mostly collected and published in the West (e.g., books on the decrypted Venona documents, the Mitrokhin Archives, and the excellent work of the British historian Christopher Andrew).

Thumbs up! This is an excellent translation of an absorbing, poignant biography, encyclopedic in its extent, moral in its tone, graphic in its depiction, enlightening in its understanding — all this, despite my gentle criticisms. This is the first and most complete biography of Stalin up to the time of Gorbachev’s glasnost period. It would be superseded only by Edvard Radzinsky’s Stalin (1996), which is also highly recommended.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002)

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy by Dmitri Antonovich Volkogonov. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 10, 2011. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/stalin-triumph-and-tragedy-by-dmitri-antonovich-volkogonov/

Copyright ©2011-2021 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.