- Articles

Dominique-Jean Larrey: Napoleon’s Surgeon from Egypt to Waterloo

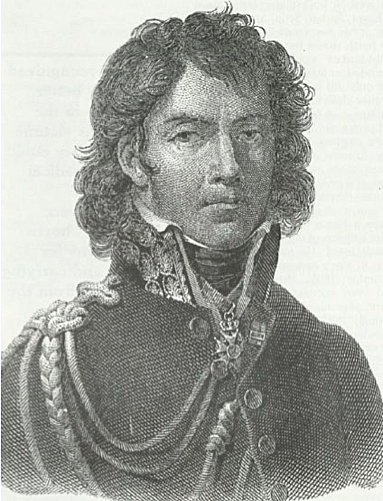

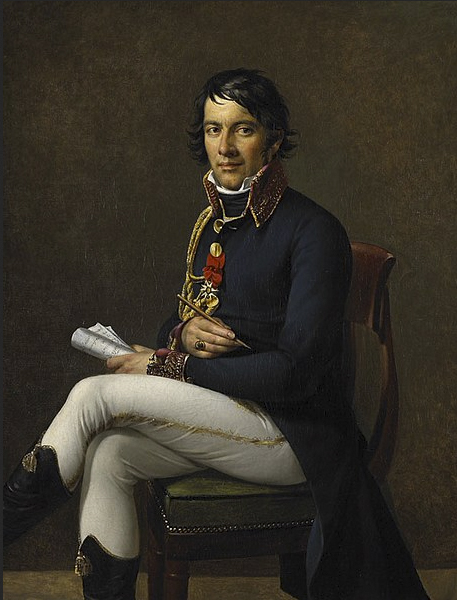

Praised by Napoleon as “the worthiest man I ever met,” Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766-1842), his legendary surgeon, was born in Beaudean, a little village in the Pyrenees. Orphaned at age 13, he was raised by his uncle, Alexis, who was chief surgeon at Toulouse. After studying and serving as his surgical apprentice for 6 years, Larrey went to Paris. There, he studied under the great French surgeon, Desault, who was Chief of Surgery at the Hotel Dieu. Unfortunately, his studies were interrupted when war came to France.

The young man promptly answered his nation’s call and signed up for duty. He was assigned to the frigate Vigilante in the French Navy, but he soon had to resign because of chronic seasickness. He returned to Paris where he worked at both Desault’s clinic in the Hotel Dieu and as field surgeon at Les Invalides. By 1790, Larrey had established himself as assistant Senior Surgeon at Les Invalides, and not long after serving in the army, he met Napoleon Bonaparte who was then commander of an artillery brigade.

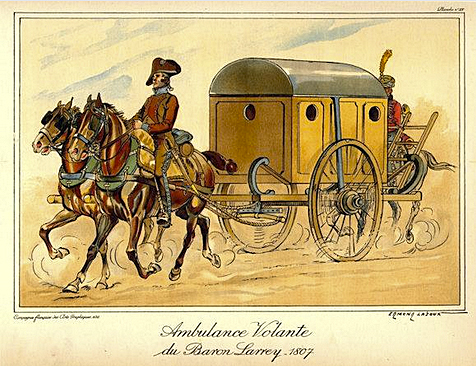

In 1792, at the time revolutionary France was battling the First Coalition, Larrey became a field doctor with the rank of Major of the Army of the Rhine. He soon recognized the need for better organization in the battlefield, as victims died before they could receive any medical assistance. It was during this period of the French Revolutionary Wars that he thought of his celebrated Ambulance Volante or “the flying ambulances.”(1) The flying ambulances were horse drawn wagons for collecting and carrying the wounded from the battlefield to base hospitals. He described this concept in minute detail in a report from the Italian Campaign of 1797. It consisted of a system of transport of medical supplies and supporting personnel. The personnel included a doctor, quartermaster, noncommissioned officer, a drummer boy (who carried the bandages), and 24 infantrymen. The flying ambulances were a success, and this idea was subsequently taken up by other armies.

Larrey was soon organizing flying ambulances for the entire French Army. This transport system served not only as a boost in morale for the rank and file officers of the French Revolutionary Armies, but it also effected a greater and realistic opportunity for the treatment and survival of the wounded. Moreover, his attention to the wounded on both sides of the battlefield was a noble concept for which Larrey should be credited. These revolutionary ideas for the care of the wounded survived to modern times in the form of the Red Cross.*

During the brief peace that followed the Italian campaigns of 1797, he became Professor of Surgery at the military hospital of Val-de-Grace where his statue still stands. He was given great recognition for his achievements, and Napoleon appointed him Chief of the Medical Corps during the planning of the forthcoming Egyptian campaign (1798-1799).

In Egypt and the Middle East,** despite enormous hardships, Larrey’s indefatigable energy served him well. He built military hospitals in Egypt, Sudan, Syria, and Palestine. It has been said that even in the harsh desert terrain, his flying ambulances would collect the wounded in less than 15 minutes. Not only did he prove his administrative skills but also his practical abilities — at Accra (1799) he himself performed 70 amputations and seven trepinations. He also found time to write about endemic diseases such as typhus, bubonic plague, leprosy, and trachoma.

Upon returning from the Egyptian campaign (August 1799), he was made a baron by Napoleon and chief surgeon of the Emperor’s Imperial Guard. He followed Napoleon in every campaign including Austerlitz (1805), Moscow (1812), and even accompanied the Emperor after his escape from Elba through “the hundred days” and to Waterloo (June 18, 1815). He served honorably in 25 major campaigns including 60 large battles during the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. It has been said that the Duke of Wellington observed and commended him for his energy and valor in tending the wounded during the Battle of Waterloo.

During the War in Spain (1808), Larrey had ample opportunity to study leg amputation. The Spaniards mined the roads of retreat resulting in a large number of casualties and lower extremity injuries. As senior field doctor in both Corsica and Spain, he learned and perfected his technique of leg amputation as well as the treatment of frostbite. This experience was later to prove valuable in the disastrous Russian campaign of the winter of 1812.

It was during this retreat from Moscow that Larrey also observed that those legs frozen stiff felt almost no pain during amputation. Moveover, after amputation, pain was diminished by packing the stumps in ice and snow. He put this knowledge to good use to alleviate the suffering of those wounded.

It was Larrey’s skills in amputations for which his name is still remembered. It has been said that he himself performed 200 amputations within a 24-hour period after the Battle of Borodino in 1812. At the Battle of the Berezina during the disastrous retreat from Russia, he performed 300 more amputations. He was revered by the men in the ranks. At the almost impassable Berezina River, they passed him over their heads from man to man to safety.(3) He also performed the first hip joint amputation in 1803. An interesting account of a woman who underwent a mastectomy by the Baron at her home in 1810, recently appeared in the surgical literature.(4) Noteworthy in the account is the woman’s adoration for her surgeons, especially Dr. Larrey, despite her ordeal (no anesthesia) and in turn, the Baron’s compassion for his patient.

For the care of wounds, Larrey substituted wet dressings for the dry lint used mainly at that time. He dipped his lint in hot wine to which he added camphor. For the first time, bullets were extracted from wounds by making a counter opening instead of probing the torn entry path of the bullet. Also, prophylactic incisions were made near bayonet wounds to let the pus flow out.(5) Larrey was also credited with saving three victims of penetrating chest injuries during the Napoleon war — up until the 20th century, there was little hope for injuries that penetrated the pleural cavity. He has also been reported to have saved a man with a self-inflicted stab wound to the heart. Because of this and other great accomplishments, he was highly respected by friends and foes alike. He was adored by the public and much admired by his colleagues while living in one of the most turbulent times of history. His name has been overshadowed by other French contemporary health professionals who were given a place in history because of their political notoriety. Chiefly, among these figures stand the chemist Antoine Lavoisier and the physicians Joseph Guillotin and Jean Paul Marat. ***

After Waterloo, the Baron was captured and imprisoned by the Prussians and quickly given a death sentence. Fortunately for the good doctor, he was recognized by a German physician who had been his student at Val-de-Grace. He pleaded for Larrey’s life with Marshal Blüicher. Fortune indeed intervened: Blüicher’s son had once been wounded in a skirmish and taken prisoner by the French. As it turned out, his life had been saved by Dr. Larrey. The Baron was released and returned to France with a Prussian escort.

Later in his career, he was the most popular surgeon of his time and in his old age, he enjoyed a comfortable life, writing his memoirs which were invaluable to later medical researchers as well as historians. Recognizing his personal physician and loyal friend, Napoleon, while exiled on the island of St. Helena, is reputed to have said, “Larrey was the most honest man and the best friend to the soldier that I ever knew.”(7) In his testament, the Emperor rewarded his courageous surgeon: “To the French Army’s Surgeon General, Baron Larrey, I leave a sum of 100,000 francs. He is the worthiest man I ever met.(1)

Footnotes

* This tribute to Larrey does not detract from the credit due to the Swiss humanitarian Jean Henry Dunant (1828-1910) for the founding of the Red Cross.(2)

** Where Napoleon fought and won the Battle of the Nile in July 1798 but lost the Battle of Abakir Bay with the destruction of the French fleet by Admiral Nelson on August 1, 1798.

*** Dr. Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, a founding father of modern chemistry, discovered the role of oxygen in combustion and metabolism. He also was the initiator and proponent of the metric system of weights and measurements which was adopted by the French Revolutionary Convention in August 1793.(6) Lavoisier was hurried to the scaffold complaining that he had not been given enough time to finish a paper on chemistry. He, like many other aristocrats, was beheaded during the Terror.

Dr. Joseph Ignace Guillotin was the professor of anatomy who devised the macrotome that bears his name. To the guillotine, 20,000 men, women, and children lost their heads during the Reign of Terror (June 1793-July 1794). Dr. Guillotin survived the contraption of his invention as well as the French Revolution.

Lastly, Jean Paul Marat was the most famous physician of the French Revolution. He was stabbed to death in his bath on July 13, 1793, by Charlotte Corday, a young woman seeking revenge for her father’s death, who had been a political enemy of Marat. Corday followed her father to the guillotine for her revenge.

References

1. Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. Leuven, JV (editor and translator), New York, Bell Publishing Co, Ist Ed, 1988.

2. Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. Medicine: An Illustrated History. Rawls W (Ed), New York, Harry N Abrams, Inc., 1978.

3. Newman A. The Illustrated Treasury of Medical Curiosa. New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co, Ist Ed, 1988.

4. Robinson JO. On the cutting edge of the knife. Surgical Rounds April 1988; 61-83.

5. The French Revolution: A revolution in medicine, too. Hosp Prac November 1977; 127-138.

6. Brinton C, Christopher JB, Wolff RL. A History of Civilization. New Jersey, Prentice Hall, Inc., 3rd Ed, 1976.

7. O’Meara BE. Napoleon In Exile. London, Simpkin W, Marshall R, 4th Ed, 1822.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Faria is editor emeritus of the Medical Sentinel, author of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002).

Originally published in the Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia (JMAG), September 1990, pages 693-695.

Copyright©1990 Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia.