- Articles

Socialized (Free) Medical Care in Cuba (Part I): A Poor State of Health

Those in the United States who yearn for a more “egalitarian” and “equitable” system of medical care “like the one in Cuba” are not familiar with the extraordinary saga of Cuban physician Dr. Dessy Mendoza Rivero, who has managed to get the word out for anyone willing to listen. And they should. ¡Dengue!-La Epidemia Secreta de Fidel Castro (Dengue! The Secret Epidemic of Fidel Castro) is the title of his book and one that should be read attentively.

Dr. Dessy Mendoza Rivero’s saga is a perfect vehicle to discuss and expose the realities of Cuba’s universal “free” socialized system of medical care.

In this book, we learn that Cuba’s health care system is in fact in shambles, a veritable disaster, a disgraceful tragic regression from the once advanced medical care system of the 1950s in the pre-Castro years.

The Arrest of a Medical Dissident

The book begins with Dr. Mendoza’s dramatic arrest at his home in his native city of Santiago de Cuba, the country’s second-largest city, located on the easternmost portion of the island and home of the Sierra Maestra mountains.

Dr. Mendoza’s crime was that of investigating, revealing, and forcing the communist dictatorship to admit the existence of a raging epidemic of dengue fever in the spring and summer of 1997. In fact, Dr. Mendoza was on the telephone with a Miami radio station communicating the details of the epidemic to the outside world when the Cuban State Security political police closed in:

“There are approximately 13 dead, 2,500 hospitalized patients, and 30,000 people afflicted!” Mendoza frantically declared, warning the interlocutor on the other side of the telephone line that the communication would be cut at any moment, as State Security had surrounded the house and was knocking on the door.

The Secret Epidemic of Hemorrhagic Dengue Fever

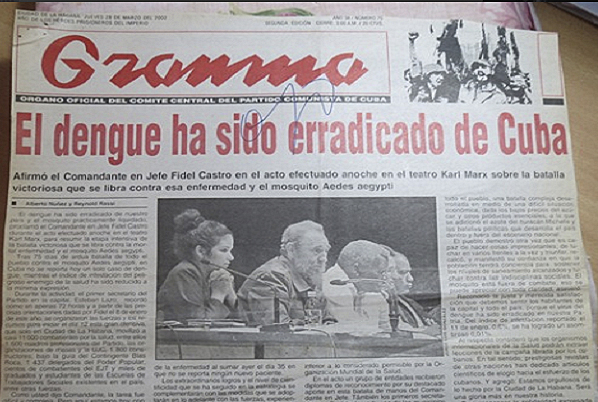

The communist regime did not want to reveal to the world the existence of the epidemic because it was a personal embarrassment to Fidel Castro, who had previously declared that the mosquito responsible for dengue, the Aedes aegypti, had been eradicated long before—by the long arm of the Revolution!

More importantly, such a disclosure endangered the burgeoning Cuban tourist industry, which at the time was in high gear preparing for the Santiago Carnival, the Expo Caribe 1997 celebration, the World Youth and Students Festival, and “a marathon of cultural and propaganda events planned for Santiago de Cuba that year.”

Because the Cuban communist authorities in the public health system kept the epidemic hush-hush, calling the disease “an unspecified virus,” the people continued to medicate themselves with aspirin for the prodromal (early flu-like) viral symptoms of the disease, tragically worsening the hemorrhagic manifestations of the disease.

Aspirin, about the only medication available to ordinary Cubans for any disease, aggravates bleeding by impairing the ability of platelets to agglutinate and coagulate bleeding sites. Dr. Mendoza describes some hapless patients who bled from every body orifice and suffocated on their own blood because of the bleeding tendency of the disease, worsened by the antiplatelet effects of aspirin.

And yet Dr. Gustavo Kouri, head of Cuba’s Institute of Tropical Medicine, violated Hippocrates’ precepts of medical ethics when, in the midst of the epidemic, under the direction of Fidel Castro and to guarantee his own safety, in a cowardly manner certified that there was no dengue epidemic and even falsified details about the disease to the media and the public in a campaign of disinformation—for example, claiming that the mosquito Aedes aegypti did not breed in dirty, stagnant water or in marshes but rather in clean, potable water!

Be that as it may, Dr. Mendoza was arrested, separated from his wife, Caridad Pin “on (also a courageous, dissident physician), and their small children who, to make matters even more desperate for the valiant physician, were ostracized by their neighbors. Dr. Mendoza was then solemnly condemned to eight years in prison for the crime of “disseminating enemy propaganda.” And this, despite the fact that the government less than one week later was forced to admit the existence of the deadly epidemic.

But Dr. Mendoza had succeeded in getting the attention of the foreign press, and Amnesty International declared him a prisoner of conscience. He served 18 months in the horrible Boniato prison under subhuman conditions before he was released in the wake of mounting international pressure. Once free, Dr. Mendoza was then forced into exile by the communist regime.

Socialized Medicine and the Caribbean Gulag

Besides the trying details of his life in communist Cuba—his clamoring for workers’ rights, his fight for independent unions for health professionals, and his efforts at founding an independent medical association—what Dr. Mendoza tells us about the realities of Cuba’s health care system deserves to be told to a wider, English-speaking audience.

Yes, there are still many influential “authorities” in this country who still believe that a universal, “more equitable” system of health care “like the one in Cuba” is worthy of imitation. Dr. Mendoza’s testimony should serve as an antidote to those who are peddling the venomous snake oil of socialized medicine—like that in socialist Cuba.

Dr. Mendoza reminds us that for more than 30 years, even during the alleged “golden years of the Revolution,” milk has been distributed by the ration book only to children up to 7 years of age and to the elderly. Everyone else wanting milk must obtain it on the black market and risk imprisonment.

With such privations, it is not surprising that malnutrition, including vitamin deficiencies, such as lack of thiamine causing peripheral neuropathies and blindness (beriberi) is rampant. We also learn that in order to feed their families, a vast proportion of the estimated 180,000 to 200,000 “common criminals” confined to Cuba’s 500 prisons are people who have violated the law by killing their own pigs, cattle, and even horses and selling the excess meat on the black market.

The Boniato prison, where Dr. Mendoza was held, was built in the 1940s to contain no more than 720 prisoners. Yet, while he was confined there in 1998, there were 2,200 men serving long, harsh sentences for such crimes. Nor should we neglect to state that with such a humongous penal colony, Cuba has become a veritable gulag where, Dr. Mendoza informs us, “acute diarrhea, parasitic infestations, amebas, gastritis and gastric ulcers, etc., are rampant due to the dire conditions of hygiene and sanitation, the meager allotment of clean water, and the horrible, rotten food rations distributed to the prisoners.”

Hygiene and Sanitation in a Workers’ Paradise

“The Cuban people suffer in silence,” writes Dr. Mendoza, “assailed by successive infestations and epidemic diseases due to the deteriorated conditions of the public health infrastructure, the contamination of rivers, streams, and Cuba’s once beautiful bays and coastline.” One reason for so many outbreaks of pestilential diseases, such as acute diarrhea, leptospirosis (from the vast rat population), hepatitis (fecal-oral contamination), typhoid fever, etc., is because of the poor state of hygiene and sanitation on the island.

Sources of potable water are frequently contaminated by runoff from old, leaky pipes (plumbing that preceded the 1959 Revolution) and potable water coming in contact with raw sewage. It is not unusual to see fecal material seeping from the ground and floating in stagnant water in the streets!

Hospitals are not exempt to the deplorable, unsanitary conditions. Cockroaches and mice roam the hospital wards. Floors are dirty because of lack of cleaning material, detergents, and the overall lamentable unhygienic milieu of the Cuban health care system. Hospital gowns, linen and towels must be brought to the hospital and cleaned by the patients’ families.

Poor sanitation is extended to medical instruments handled by doctors and nurses; these are not properly sterilized and frequently remain dirty with the remains of tissue and blood after their use. Syringes are frequently used to inject different patients without any sterilization, and “disposable” gloves are used and reused on different patients. Not surprisingly, infectious diseases such as impetigo and hepatitis and infestations such as scabies, lice, and fungal diseases are also commonplace in the population.

Predictably, hospitals for ordinary Cubans have a dearth of the most basic medicines and medical equipment to care for patients. Doctors have no sphygmomanometers to measure blood pressure, sterile gloves, sterile water for diluting injections, syringes, soap, disinfectants, and the most basic items that one would expect in hospitals and clinics.

Dr. Mendoza points out the most essential medical equipment is not available, not because of the embargo but because of the misallocation of priorities and a perverse system of tourism and health apartheid that has developed in Cuba under the auspices of the communist (fascist) regime. As we shall see in Part II of this essay, clinics that cater to tourists and the privileged mayimbe class have the latest medical technology.

And yet, Dr. Mendoza reminds us, in the pre-Castro years of the 1950s, Cubans had excellent access to medical care through association clinics (clinicas mutualistas), which predated the American concept of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) by decades, as well as through private clinics. Notwithstanding the regime’s published statistics, according to Dr. Mendoza, the standard of living and the state of health of the Cuban people were far better in 1958 than they are today, making evident the direful state of medical care regression since Castro’s communist takeover.

It is no wonder that one of the goals of the Colegio Médico Independiente de Santiago de Cuba, founded by Dr. Mendoza, is to at least return the Oriente district to the state of salubrious health that prevailed in the 1950s!

In the concluding Part II of this essay, we will have a few words to say about Castro’s attempt to export socialized medicine to the United States and other countries, his “doctor diplomacy,” as well as reveal other aspects of the hidden face of Cuba’s socialized (“free”) system of medical care, such as sex tourism and medical apartheid.

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

Macon, Georgia

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D., is a retired neurosurgeon and editor emeritus of the Medical Sentinel and author of “Vandals at the Gates of Medicine” (1995); “Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine” (1997); and “Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise” (2002). His books are available from https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Socialized (Free) Medical Care in Cuba (Part I): A Poor State of Health. HaciendaPublishing.com, August 1, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/socialized-free-medical-care-in-cuba-part-i-a-poor-state-of-health.

Unillustrated versions of this article were published in NewsMax.com, August 20, 2002, and in Surgical Neurology 2004;62(2):183-185.

Copyright © 2004 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.