- Articles

From the Heroism of the Knights of Malta (1565) to the Victory at the Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Galleys at Lepanto by Jack Beeching (1982) is a marvelous book, so well researched and mellifluously narrated as to read almost as a fairy tale or an epic romance of yore, elegantly scribed in poetic prose. Foremost among the knights-errant in this tale of chivalry is Don John of Austria, illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and half-brother of the stern King Philip II of Spain. The characters come to life as they are vividly described in the enthralling narrative, thus once begun, the tome is very difficult to put down. Intrigue, perils, and tales of heroism galore at Rhodes, Malta, and Cyprus await the reader before the denouement at the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571.

We also learn about the main protagonists and their characters and the shaping events in their lives — Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Pope Pius V, Grand Master and Knight of Malta, Jean de la Valette, and the uncharacteristic childhoods of King Philip II of Spain and his half-brother Don John of Austria, as well the dispositions of their main adversaries, Ottoman Sultans Suleiman the Magnificent and his depraved son, Selim II “the Sot”, their Grand Viziers, and the Barbary Coast corsairs of North Africa in the employ of the Ottomans, i.e., Barbarossa, Dragut, and Ochialli.

The book reads as a suspenseful novel but it is true history. As the drama and conflict unfold between the Turks in the East and the Catholic powers in the West, the book reaches a dramatic pinacle with the indomitable heroism displayed by the Christian Knights in the defense of Malta in 1565. The heroic Knights of Malta, led by Grand Master Jean de la Valette in their brave and obstinate defense, repulsed the repeated attacks of the Turks, including the Janissaries, the elite troops of the Ottoman Sultan. Seven hundred Knights and their men-at-arms defeated a Turkish army and navy consisting of an invasion force of 40,000 well-disciplined soldiers and 180 ships of which 150 were war galleys, a feat unparalleled in history. Their stout defense and heroism showed Christian Europe that the Turks were not invincible, setting the tone for the decisive climax of the book only a few years later at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

Such a victory at Malta, the Knights defeating a superior force that outnumbered them by twenty to one, emboldened King Philip II of Spain, Pope Pius V, Genoa, and the Venetian Senate to finally join forces in a tenuous alliance to fight the advancing star and crescent banner of the feared and terrible Turks, led by their enlightened Sultan Suleiman. For the first time the Turks had been defeated. The Islamic wave could be defeated again.

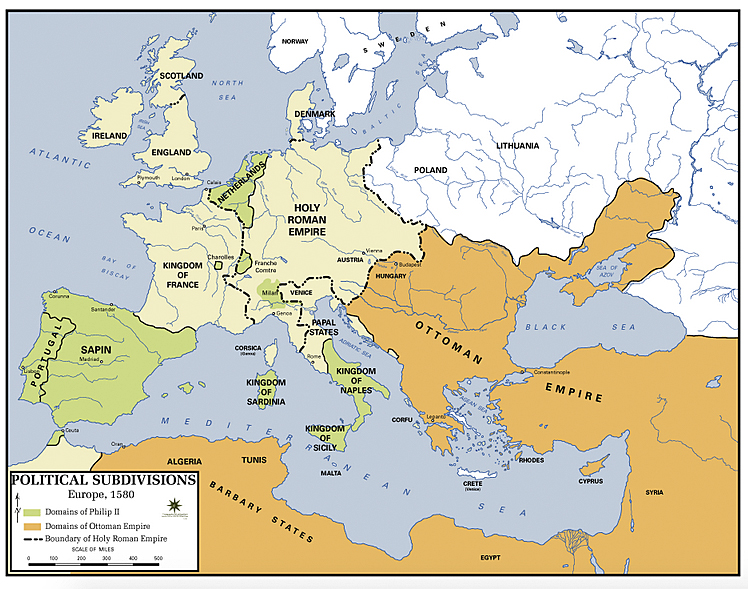

For the Ottomans, years of wars and conquests were not only gains for Islam, but also highly profitable enterprises bringing tribute, slaves, and untold wealth to the empire. But after Malta, for the first time ever, the sultan could not meet payment for his troops, and the currency had to be devalued 30%, the Sublime Porte even having to import bullion from the West. For their part, the Knights of Malta were the sensation and heroes of all of Europe, and the morale of the West was lifted from the nadir where it had fallen following the repeated conquests of the Turks that began in earnest with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the collapse of the remnant of the Byzantine Empire, opening the Balkans and Eastern Europe to the seemingly unstoppable Ottoman conquests. In fact, in the south, the eastern Mediterranean had become an Ottoman lake, and in the north, Ottoman expansion had reached the gates of Vienna in Central Europe.

In 1569 the Moriscos of Spain, who had been in touch with the Turks, revolted and created a rebel Moorish Kingdom of Alpujarras, but the Turkish assistance did not materialize following their disastrous defeat at Malta. The revolt was thus suppressed by Spanish troops under Don John of Austria.

Another interesting incident narrated was the description and importance of the workings and production of the shipyard and Arsenal of the Republic of Venice, the key to the Venetians survival in the shadow of the Ottoman Turks. It was here that the technique of standardization of parts and assembly line production were invented and mastered. But then comes an unexpected seemingly cataclysmic event: the destruction of this critical Arsenal, blown up, possibly by sabotage conducted by the Sultan’s economic wizard in Constantinople, the Jewish banker and advisor, Joseph Micas. We fear for the Venetians as if we were there and weaved in as part of the story!

Suleiman had envisioned the conquest of Christendom in an all out confrontation with the major European powers (except the French and the Dutch, who were tacit allies), invading Western Europe after dispossessing Venice of all her possessions by using the Ottoman fleet and his corsairs, and even capturing Rome, which he dubbed the Red Apple, and converting St Peter’s Cathedral into a mosque, where he had vowed to worship Allah. He was wont to dismiss his generals going to war, “We will see each other in the Red Apple!”

Another thrust was to come about via Central Europe after first conquering Vienna and the Holy Roman Empire of the Hapsburgs. But Suleiman, in fact, dies in 1566 at the gates of Vienna, which he failed to take, and his son, by his influential wife Roxelana, then succeeds him as Ottoman Sultan Selim II. Each Ottoman Sultan was expected to add territory to the Sublime Porte and wealth to the treasury and to build a new mosque for Islam. The renewed effort for war was resumed in 1570 with the intended annexation of the island of Cyprus by force of arms.

At the instigation of the banker Joseph Micas (also referred to as Nasi), Selim vowed to take Cyprus, a possession of Venice. Micas sought more profits as well as the creation a Jewish homeland with himself as King of Cyprus. In 1570 Nicosia is taken by bloody assault and sheer numbers, and in 1571 in the next campaign season, the fortress of Famagusta, the second Venetian stronghold on Cyprus, became another Malta, a drawn out sanguinary affair defended stoutly by the desperate Venetians and Cyprians. Finally after much bloodshed, the Turkish commander, Lala Mustafa, arranged for an honorable truce, promising safe conduct to the few defenders surviving the siege. Mustafa, instead, ignominiously arrested and then massacred the brave Venetians, including their commander, the Venetian Senator Marcantonio Bragadino, who was tortured, mutilated, and finally executed, being flayed alive.

At this point in the narrative, Beeching notes that “with Cyprus added at long last to the Ottoman Empire, Selim had qualified like every sultan before him for the title of Extender of the Realm.” But Beeching also very astutely remarks that additionally Sultan Selim II was “toying with the dream of fulfilling another old prophecy — that true believers would one day say their prayers to Allah beneath the dome of St Peter’s.“ [p. 199]

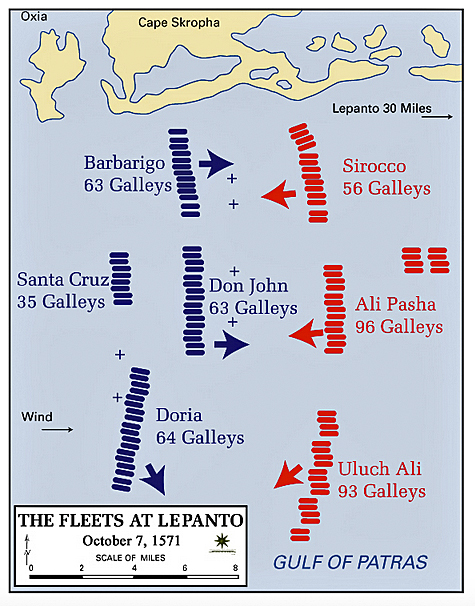

The heroic resistance of the garrison, their betrayal, and cold-blooded massacre at Famagusta, inflames the Venetians, who finally iron out their differences with the Spanish, the Pope, and the distrusted Genoese, and agree to go to war against their feared enemy, formally joining the Holy League against the Turks. Pope Pius V and King Philip II of Spain appointed young Don John of Austria Commander-in-Chief of the newly created Holy League fleet and army. Don John was the only man capable of holding together such a combined allied navy consisting of former friends and enemies, including the Genoese and Venetians who hated each other. The titanic clash between the two superpowers of East and West took place October 7, 1571. It was the last great sea battle fought with galleys in the Mediterranean. The dramatic crescendo reaches a peak as the two fleets approach each other off Lepanto in the Gulf of Patrae, only a few miles south of Actium, where the fleet of Marc Antony and Cleopatra had been defeated in another colossal naval encounter of ancient times.

Suffice to say the Turks were decisively defeated and the fascinating dramatic details are discussed in detail, as is the life of Don John of Austria until his death in the Netherlands in 1578 at the age of 31. Incredibly, several historians have argued that because the Ottomans quickly rebuilt their fleet, the Battle of Lepanto’s importance has been overstated. This attitude takes a very narrow and shortsighted view of history. Extolling victories of Christendom or of Western civilization has been out of vogue for sometime, probably since the age of Voltaire and the French philosophes, and this attitude has probably intensified in the zeitgeist of our own, even more secular and multicultural time. But be that as it may, these historians are sadly mistaken.

The heroic defense of Malta with the defeat of the Ottoman army (including its formidable Janissaries) in 1565, followed subsequently by the even more serious destruction of the Ottoman fleet off the coastal town of Lepanto in 1571, despoiled the image of Turkish invincibility on land or at sea.

The Battle of Lepanto halted the Ottoman Turks’ advance into the Western Mediterranean and Europe, virtually saving Western civilization from utter collapse, which would have resulted if the Turks had been victorious. Although the Turks did indeed (and very quickly) rebuild their fleet after Lepanto, their new galleys were hastily and shoddily constructed and they ended up rotting in their berths, without ever again systematically attempting to conquer the western Mediterranean or seriously challenging Christendom.

The naval defeat at the Battle of Lepanto resulted not only in the physical destruction of the Turkish fleet, but also inflicted a psychological defeat on the losers. At the same time, it resulted in general jubilation, rejoicing, and a tremendously uplifting of morale in Christendom and the West.

The Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire lingered on for many years, but after their defeat on Malta, the death of Suleiman and the naval disaster at Lepanto, the Ottoman Sultanate began a slow and inexorable decline. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Ottomans had to be propped up by the British and the French to preserve the balance of power in Europe, and more apropos, protect Constantinople from expansionist Tsarist Russia. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia began to refer to the Ottoman Empire as “the Sick Man of Europe,” and the label stuck because it fit in historical terms.

Read this book for a historic treat, a book that truly belongs in the working library of the discriminate historian or history connoisseur. The Galleys at Lepanto (1982) by English author Jack Beeching is thoroughly enchanting and thus highly recommended without caveats to each and everyone with even a modicum of interest in history and the course of Western civilization.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is a medical historian, and an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI). He is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002), and numerous articles on political history, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011); “Stalin, Communists and Fatal Statistics” (2011); “The Political Spectrum — From the Extreme Right and Anarchism to the Extreme Left and Communism” (2011); “Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery” (2013).

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. From the Heroism of the Knights of Malta (1565) to the Victory at the Battle of Lepanto (1571). HaciendaPublishing.com, February 15, 2014. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/from-the-heroism-of-the-knights-of-malta-1565-to-the-victory-at-the-battle-of-lepanto-1571.

(The Galleys at Lepanto by Jack Beeching, 1982. Scribner’s Sons, New York, NY, 268 pages, Illustrated with Bibliography and Index.)

The photographs used to illustrate this book review for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not appear in Beeching’s The Galleys at Lepanto.

An unillustrated version of this book review appears on Amazon.com.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.