- Articles

Alexander Hamilton — American patriot, financial genius, builder of the United States!

A book review of Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow (2004)

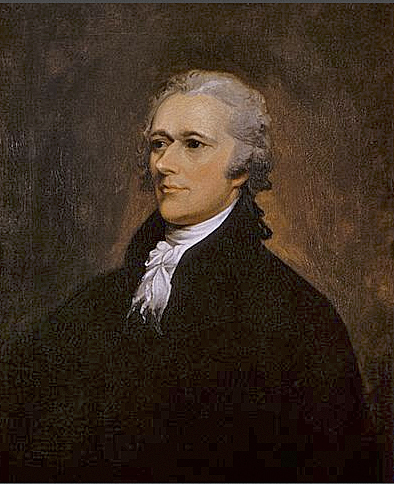

This book is the most comprehensive biography of Alexander Hamilton released in modern times. It tells the story well and is written in florid detail supported by a fount of scholarly research and previously undisclosed material from Hamilton’s voluminous writings. Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) was born in the West Indies (Nevis), descended from the laird of Grange in Scotland on his father’s side of the family and from French Huguenots on his mother’s side. Brought up in relative poverty, Hamilton was soon recognized as a child prodigy by Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian minister in the islands. As an extremely proficient clerk at a Counting House in St. Croix, young Alexander Hamilton’s employers also appreciated his precocity and intelligence. Knox arranged for Hamilton, now age 17, to receive financial assistant from the admiring islanders, who backed Hamilton to travel to America and study on scholarship. America was then a land in revolutionary turmoil, rebelling against British rule. As a student, Hamilton soon became embroiled in the heat of politics and revolution. Hamilton studied at Kings College (later Columbia University) in New York, but as open rebellion erupted in America, Hamilton joined the ranks of the revolutionaries. He wrote incendiary articles, orated for the revolution, and when war came he served as an artillery officer in the New York militia. Discovered by George Washington, Hamilton was made an military adjutant and promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the Revolutionary Army. He was commissioned and served six years under George Washington (1776-1781), became a hero of the Battle of Yorktown (1781), served brilliantly as Secretary of the Treasury (1789-1795), and later as Deputy Chief of the U.S. Army (as Major General; 1799-1800).

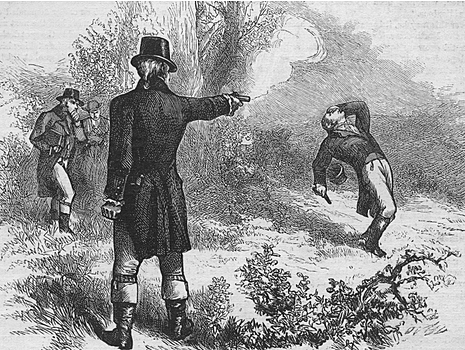

A passionate and controversial figure, Alexander Hamilton established the basis for the economic powerhouse that the United States of America would become, only to be senselessly killed in a duel by Aaron Burr, the Vice President of the United States at the rocky ledge of Weehawken, New Jersey across the Hudson River on July 12, 1804. Upon learning of his death, there was general lamentation in New York and other Federalist city strongholds, such as Boston and Philadelphia. Charles Biddle, Aaron Burr’s friend, admitted there was as much lamentation as when George Washington died. Alexander Hamilton’s public funeral was financed by the merchants of New York. Historian Ron Chernow describes the funeral scene: “…New York militia units set out at the head of the funeral procession, bearing their arms in reversed position, their muzzles pointed downward. Numerous clergymen and members of the Society of the Cincinnati trooped behind them…. Preceded by two small black boys in white turbans, eight pallbearers shouldered Hamilton’s corpse, set in a rich mahogany casket with his hat and sword perched on top. Hamilton’s gray horse trailed behind with the boots and spurs of its former rider reversed in the stirrups.” (p. 711)

Hamilton was both hated and loved with passion. There was no middle ground for the sentiments he evoked during his lifetime. Nevertheless, both friends and foes marveled at his genius. Chernow’s book has an interesting amalgam of opinions about Hamilton by famous contemporaries who knew him:

New York Judge Ambrose Spencer who frequently presided over legal courtroom battles opined that Hamilton “was the greatest man his country ever produced… In power of reasoning, Hamilton was the equal of [Daniel] Webster… In creative power, Hamilton was infinitely Webster’s superior.” (p. 189)

Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story stated, “I have heard Samuel Dexter, John Marshall, and Chancellor (Robert R.) Livingston say that Hamilton’s reach of thought was so far beyond theirs that by his side they were schoolboys—rush tapers before the sun on noonday.” (p. 189)

Fisher Ames commented, “With other men, law is a trade, with him [Hamilton] it was a science.” (p. 190)

Reverend John M. Mason called Hamilton “…the greatest statesman in the western world, perhaps the greatest man of the age….” (p. 714)

Alexander Hamilton’s friend Robert Troup said, “I used to tell him that he was not content with knocking down [his opponent] in the head, but that he persisted until he banished every little insect that buzzed around his ears.” (p.190)

John Quincy Adams — son of one of Hamilton’s most vociferous critics and intemperate enemy, John Adams — admitted that Hamilton’s financial system “operated like enchantment for the restoration of public credit.” (p. 481)

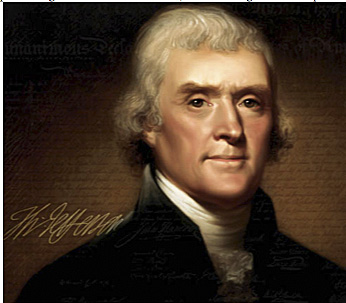

Occasionally his political enemies rendered backhanded praise for Hamilton. Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend and collaborator James Madison at about the time of the debate on the Jay Treaty (a winning political issue for the Republicans) in 1793: “[Hamilton] is really a colossus to the anti-Republican party. Without numbers, he is a host [i.e., an army] within himself… We have only middling performances to oppose him. In truth, when he comes forward, there is nobody but yourself, who can meet him.” (p. 496) Madison did not accept the challenge. He opposed Hamilton legislatively but not with the pen, and the Treaty was approved for the good of the country, which was totally unprepared for war.

When Jefferson was President of the United States, he charged Albert Gallatin, his new Secretary of the Treasury and a political foe of Hamilton’s, to rifle through files, dig up any financial material in the Department incriminating Hamilton of malfeasance. Gallatin went at it with gusto. Gallatin wrote years later: “Well Gallatin, what have you found? [Jefferson asked]. “I answered: ‘I have found the most perfect system ever formed. Any change that should be made in it would injure it. Hamilton made no blunders, committed no frauds. He did nothing wrong.’ ” (p. 646-647) Despite their criticisms, both Jefferson and Madison as Presidents left the Hamiltonian economic system largely in place.

And praise for Hamilton was not restricted to sectarian Americans. The French Revolution exile, the duc de La Rochefoucald-Liancourt noted, “the lack of interest in money, rare anywhere, but even rarer in America is one of the most universally recognized traits of Mr. Hamilton.” In fact, although Hamilton would not take cases in which he deemed the defendant guilty, he frequently undertook to defend many indigent legal cases. (p. 188)

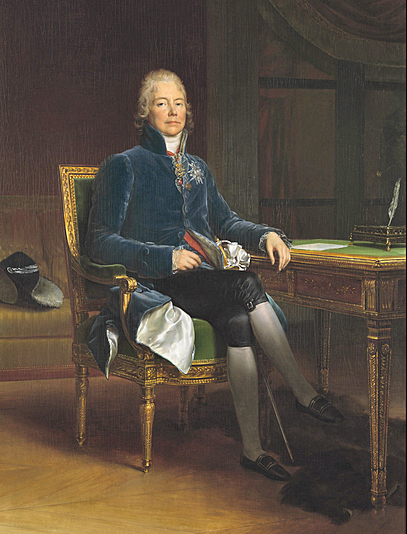

And the famous Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, arguably the greatest diplomat-statesman in history, who got to know Hamilton during his two year exile in America, marveled at Hamilton’s honesty and integrity, but most of all his intelligence. Talleyrand opined: “I consider Napoleon, Fox, and Hamilton the three greatest men of our epoch and, if I were forced to decide between the three, I would give without hesitation the first place to Hamilton. He divined Europe.” Talleyrand further told an American traveler that he had known nearly all the marked men of his time, but that he had never known one on the whole equal to Hamilton. (p. 466) After his treason trial in 1807, Aaron Burrtraveled in Europe for four years. While in Paris, Burr called on Talleyrand who was then Foreign Minister for Napoleon. Talleyrand told his secretary to tell Burr, “I should be glad to see Colonel Burr, but please tell him that a portrait of Alexander Hamilton always hangs in my study where all may see it.” Wittily, Chernow states that “Burr got the message and left.” (p. 720)

Posterity, in the voice of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge has justly judged Hamilton: “We look in vain for a man who, in an equal space of time, has produced such direct and lasting effect upon our institutions and history.” (p. 481) And Ron Chernow himself, who remained for the most part objective and dispassionate in the book, wrote: “If Washington was the father of the country, and Madison the father of the Constitution, then Hamilton is the father of the American government.” (p. 481)

In conclusion, Hamilton championed the executive branch of government and an independent judiciary, strengthening the national government. He succeeded with almost all the programs he conceived, including the First Bank of the United States, which promoted commerce; the funding of the national debt that provided financial confidence in the new nation; the American tax system that funded constitutional government; the efficient Custom Service, which largely funded the national debt; the inception of the Coast Guard,which protected custom duties and guarded against smugglers — in short, America’s financial and commercial system. As Deputy Chief of the U.S. Army, Hamilton even contained the Whiskey Rebellion without bloodshed — all of which promoted the peace and prosperity of the new nation. When asked, during a dinner meeting at the historic Fraunces Tavern, “Who was right about America, Jefferson or Hamilton?”, another Hamilton biographer, Willard Sterne Randall responded briefly, “Jefferson for the eighteenth century, Hamilton for modern times.” That is a good summation with which Chernow also would have agreed.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.), Mercer University School of Medicine. Dr. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). Dr Faria has written numerous articles on Stalin, communism, and the Soviet Union, all posted at the author’s website: https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Alexander Hamilton — American patriot, financial genius, builder of the United States! HaciendaPublishing.com, August 21, 2014. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/alexander-hamilton–american-patriot-financial-genius-builder-of-the-united-states.

(Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow. The Penguin Press, New York, NY, 2004, 818 pages, Notes, Bibliography, Index.)

The photographs used to illustrate this commentary came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Alexander Hamilton — American patriot, financial genius, builder of the United States!”

This Day in History (September 1, 1807): Aaron Burr acquitted of treason — Former U.S. vice president Aaron Burr is acquitted of plotting to annex parts of Louisiana and Spanish territory in Mexico to be used toward the establishment of an independent republic. He was acquitted on the grounds that, though he had conspired against the United States, he was not guilty of treason because he had not engaged in an “overt act,” a requirement of the law governing treason…

In 1805, Burr, thoroughly discredited, concocted a plot with James Wilkinson, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, to seize the Louisiana Territory and establish an independent empire, which Burr, presumably, would lead. He contacted the British government and unsuccessfully pleaded for assistance in the scheme. Later, when border trouble with Spanish Mexico heated up, Burr and Wilkinson conspired to seize territory in Spanish America for the same purpose.

In the fall of 1806, Burr led a group of well-armed colonists toward New Orleans, prompting an immediate U.S. investigation. General Wilkinson, in an effort to save himself, turned against Burr and sent dispatches to Washington accusing Burr of treason. In February 1807, Burr was arrested in Louisiana for treason and sent to Virginia to be tried in a U.S. court. On September 1, he was acquitted on a technicality. Nevertheless, the public condemned him as a traitor, and he went into exile to Europe. He later returned to private life in New York, the murder charges against him forgotten. He died in 1836.—Historydotcom