- Articles

John Quincy Adams — From Child Prodigy and Diplomat to U.S President and Militant Abolitionist!

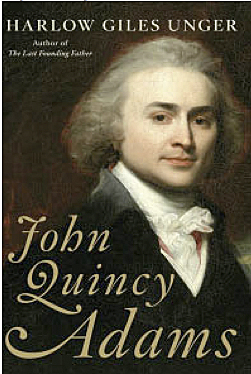

John Quincy Adams (2012) by Harlow Giles Unger is a well written and well-researched book that brings to light the sixth president of the United States, and the only son of a Founding Father to become president — John Quincy Adams. The Adams family was not only to give birth to several American statesmen, but also men of letters, diplomats, politicians, historians, and famous Americans — among them the Harvard educator Charles Francis Adams (1807-1886) and his sons, the novelist Henry Adams (1838-1918), and the historian Charles Francis Adams II (1835-1915).

After reading Unger’s previously published book about James Monroe (The Last Founding Father, 2009), I reset Monroe in a higher pedestal from that in which I had previously placed him, from my knowledge of his life and American history, and from having read W.P. Creeson’s masterpiece, James Monroe (1946). I was disposed to believe the same about John Quincy Adams. But that was not to be the case. This was not due to the author’s abilities as a writer or historian; Unger did a magnificent job as a biographer in this book. The problem was I learned more about John Quincy Adams that I previously did not know, and this knowledge, regrettably, has made me remove him from the pedestal in which he had rested in my cerebral repository. Unger admires John Quincy very much and this comes through the pages of his book, but in my case it had the opposite effect from what the author intended.

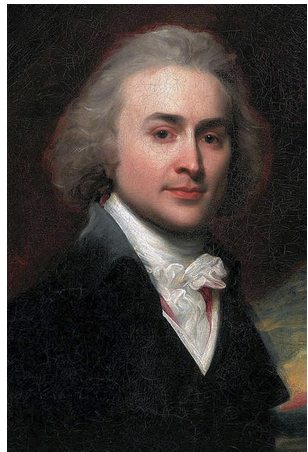

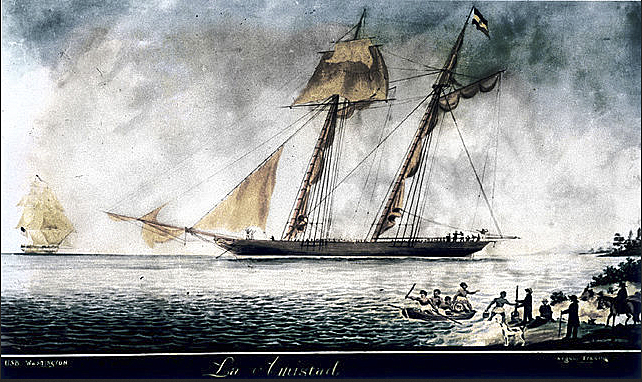

I knew John Quincy was a child prodigy, who became a master diplomat, a great intellectual, a famous scholar, while always remaining a highly religious man and a dutiful son. I knew he had followed his father’s footsteps in politics becoming a devote public servant, serving as skilled translator and diplomat in Russia and the rest of Europe, as early as a teenager, in the successive administrations of Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. I was cognizant of his role in helping negotiate and draft the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812, as the leading U.S. representative in the diplomatic mission. I was aware of his fabulously successful ministration of foreign affairs as Secretary of State for President James Monroe; his assistance in the formulation of the Monroe Doctrine and in negotiating the borders of the U.S.-Canadian frontier with the British. I was aware of his reaching the U.S presidency in 1824, with great gratification for his father, one of the nation’s most esteemed founder, who was still alive at the time. I also knew John Quincy was not an effective president, and had been defeated on his re-election bid in 1828 by Andrew Jackson, “Old Hickory” and the hero of New Orleans in the War of 1812. Jackson defeated by John Quincy in the House of Representatives at his first bid for the presidency had created a new opposition, the Democratic Party. I also knew that in his old age, as a dedicated and principled constitutionalist, John Quincy had successfully defended the band of 36 African slaves, who had been kidnaped by enslavers in the ship Amistad; they had mutinied and killed their oppressors, and had thus been put on trial in the U.S., where they had landed; their case had gone all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and they had been acquitted by the pleading and eloquent oratory of John Quincy, their savior.

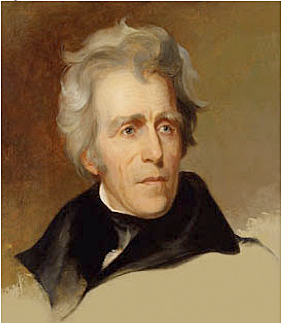

(contemporary painting, artist unknown)

This book confirms my recollections and elaborates on this knowledge with engaging prose and much enthusiasm, as Unger describes the ascending and long career of John Quincy Adams in public service. What I did not know was the extent to which John Quincy Adams had contributed to the acrimony between North and South on the issue of the protective tariffs, sectionalism, and slavery; and how he had helped push the country to civil war in the two preceding decades, despite his contention he was a representative of the entire nation and not a political party. These are not points Unger points out or emphasizes to his readers, or that he uses to criticize his hero; they are simply facts that jump out at the reader from the engaging narrative, as divisions between North and South developed in the new nation.

We must note that abolition of slavery was not an issue John Quincy tackled as U.S. President, but that he promoted only after he left the presidency and was elected U.S. Representative from Quincy, Massachusetts, when he could escape responsibility for his divisive and fierce oratory. We all know, as President Harry Truman a century later stressed, that the buck stops with the president. John Quincy’s abolitionist spirit, then, only expressed itself when he was a maverick congressman, but not earlier when he was the Chief Executive. In fact his presidency was noted for his inactivity, except for his intransigent protective tariffs that promoted Northern manufacturing interest and hurt the agricultural, cotton-producing South, and his frequent nude swimming in the Potomac, one day nearly drowning much to his chagrin and embarrassment.

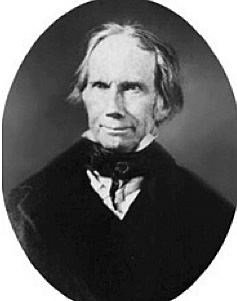

Creating divisiveness and sectionalism because of John Quincy’s newly espoused hatred of slavery and abolitionism is in extreme contrast to the stance of other American patriots who loved the Union enough to attempt to preserve it at the expense of their personal beliefs or party affiliations. I refer to Henry Clay (1777-1852, “The Great Compromiser,” despite holding contradictory views on slavery), Daniel Webster (1782-1852; who hated and fought against slavery), and Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861; “The Little Giant,” who dies untimely of typhoid fever on the eve of the war) — all of whom did everything within their political power to avoid the bloody civil war that arouse out of the contentious issues of high protective tariffs, slavery, and the right to secede. In the service of their country and seeking conciliation and avoiding civil war, Henry Clay authored the compromise of 1850; followed by Stephen Douglas drafting the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. For these men loyalty to the Union and compromise transcended personal beliefs and ideals, but not for the militant abolitionist, “the Sage of Quincy,” as John Quincy Adams was referred to by his Northern admirers.

High tariffs, the call for immediate abolition of slavery, and the right of secession were the same tinder box issues that produced the intense divisiveness and acrimony promoted by John Quincy in his incendiary speeches in the House of Represenatives and that plunged the nation a few years later into the bloody Civil War. In that fratricidal and regional conflict, 750,000 young soldiers would perish (the historian John Huddleston estimation is ten percent of all Northern males 20–45 years old and 30 percent of all Southern white males aged 18–40), as well as an undetermined number of civilians. The Civil War exacted the bloodiest and greatest toll of American lives in U.S. history. Unger is way off the mark in this book, citing an incredibly low and misleading figure of “more than 250,000.”(1)

For a man who repeatedly stated he represented the whole nation and not a section of the country and wanted the preservation of the Union, we find the following puzzling contradictions. On his first day in the House of Representative, John Quincy started the divisive debate on slavery, knowing as he predicted, that slavery, piled upon the related issues of high protective tariffs and secession, would lead to bitter acrimony and eventually bloody Civil War.(2)

John Quincy fought against and blocked appeals of Texas to join the United States because of his determination not to permit slave or possible slave states into the Union, although he had favored Manifest Destiny and Western expansion with extensive “internal improvements” throughout the nation only a few years earlier.

John Quincy, as representative from Massachusetts, had supported the Andrew Jackson administration and the Democrats in their opposition to South Carolina’s Nullification Ordinance, but he immediately turned around and opposed reconciliation when the Jacksonian Democrats offered an olive branch to the southern agricultural states by eliminating the economically crushing high protective tariffs.(3)

John Quincy opposed South Carolina’s Right to Secede Resolutions, and he went on to support Jackson, “the barbarian,” when the president told the delegates from South Carolina, “disunion is treason,” threatened armed force and enforcement of Jackson’s “Force Bill”(3). Not too long afterward, John Quincy made a convenient political volte face by reading on the floor of the House of Representatives, the Haverhill anti-slavery Petition from Massachusetts, which called for disunion! When another congressman, young Thomas Marshall of Kentucky, a nephew of deceased U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, called John Quincy’s reading of the petition “high treason,” John Quincy lambasted him, and all but sent the congressman scurrying out of the U.S. House and out of politics altogether!(4)

Black Slavery was wrong (equally wrong as the forgotten but generally accepted white [universal] slavery in ancient times), a blot on the United States, but given what we know of history and economics, slavery would have withered on the vine in the U.S., as it did everywhere else, in Great Britain, Spain, and France and their colonies, Mexico, Brazil, Cuba, Guadeloupe, etc. Only in backward Haiti did slavery end in a blood bath in which all whites indiscriminately were massacred. Most of Latin America, former colonies of Spain and Portugal, had black slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries, and not one of those countries required a bloody civil war to end it. Although in Cuba an unsuccessful war for independence had been fought between 1866 and 1876, the island abolished slavery peacefully in 1886. Brazil the largest country in South America with a large black and mixed-race population ended slavery in 1888 — and also without a war.”(5)

And yet, John Quincy divining the future affirmed:

“. . . a dissolution of the Union for the cause of slavery would be followed by… a war between the two severed portions of the Union. It seems to me that its result must be the extirpation of slavery from this whole continent and desolating as this course of events must be, so glorious would be its final issue, that, as God should judge me, I dare not say that it is not to be desired.”(6)

We cannot help liking John Quincy Adams as a child prodigy who traveled around the world, already serving his country in 1781 at the tender age of 15 years, going as far as St. Petersburg, Russia, as translator and secretary to Francis Dana. We continue to cheer John Quincy, as he ascends the diplomatic, government, and public service ladder, up to the time he enters the White House in 1824, presumably via the “Corrupt Bargain” with Henry Clay, as “Old Hickory” called it. I think this accusation is baseless, and I don’t blame Adams or Clay for aligning with each other; it was an absolutely logical but ultimately disastrous political alliance!

But after that the observant reader may begin questioning John Quincy’s aloof, detached, aristocratic manners as U.S. President. He was understandably defeated for a second term. And then, returning to Washington with a vengeance as U.S. congressman from Quincy, unprejudiced minds may question his obsessive preoccupation with politics at the expense of his family, particularly his wife Louisa, who without a doubt he neglected, as he did two of his grown but unattended children dying of alcoholism. (Unger blames inheritance from his grandmother’s side for the malady; I grant that, but also add the lack of genuine interest in his family and utter neglect, Unger’s assertions notwithstanding.) Although Unger gives short shrift to this, I believe John Quincy’s lack of concern and genuine warmth for his wife Louisa is appalling. His father, John Adams (to whom John Quincy was attentive), despite his busy existence and his long absences, remained tender and attentive to Abigail throughout their long lives.

For John Quincy, while serving in the House of Representatives in his latter years, the use of his time in throwing oratorical and incendiary bombs to the hated South on the floor of the Capitol was more important. We wonder if his bitter defeat in his presidential re-election bid in 1828 embittered him politically to foster hatred of that section of the country which had rejected him! And it was not only the slavery issue, but also high tariffs and political intransigency, which he used without mercy against the South to push Southern states over the edge. After reading this biography, I could not help liking John Quincy Adams a bit less than I used to, and considerably less than his father, John Adams, a more towering figure in my judgment. Although far from being stated as such by Unger in this book, John Quincy created as much disharmony between North and South, as John Adams strove to build harmony in creating a new Nation in 1776. It would take a catastrophic civil war to restore the Union and fill the chasm that John Quincy helped to foment in the 1830s and 1840s. This is a book worth reading, as long as we recognize some slight shortcomings, such as the fact that Unger should have pointed out to the reader the less attractive features and shortcomings of his subject, “warts and all,” as much as he underscored and applauded the achievements of John Quincy Adams.

This book is recommended for those interested in American history and wish to learn more about John Quincy Adams, the only son of a Founding Father to become President of the United States.

References

1. Unger, WG. John Quincy Adams (2012). Da Capo Press, Philadelphia. p. 312.

2. Ibid., p. 266.

3. Ibid., p. 269-271.

4. Ibid., p. 305.

5. Faria MA. Slavery and the Civil War. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 25, 2011.

6. Unger, op cit., p. 273.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is a medical historian, and an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI). He is the author of Cuba in Revolution — Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002), and numerous articles on political history, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011); “Stalin, Communists and Fatal Statistics” (2011); “The Political Spectrum — From the Extreme Right and Anarchism to the Extreme Left and Communism” (2011); “Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery” (2013).

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. John Quincy Adams — From Child Prodigy and Diplomat to U.S President and Militant Abolitionist! HaciendaPublishing.com, February 1, 2014. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/john-quincy-adams–from-child-prodigy-and-diplomat-to-u-s-president-and-militant-abolitionist.

(John Quincy Adams by Harlow Giles Unger, 2012. Da Capo Press, Philadelphia, PA, 364 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this book review for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not appear in Unger’s John Quincy Adams.

An unillustrated version of this book review appears on Amazon.com.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.