- Articles

Regimentation in medicine and the death of creativity (Part 1) by Russell L. Blaylock, MD

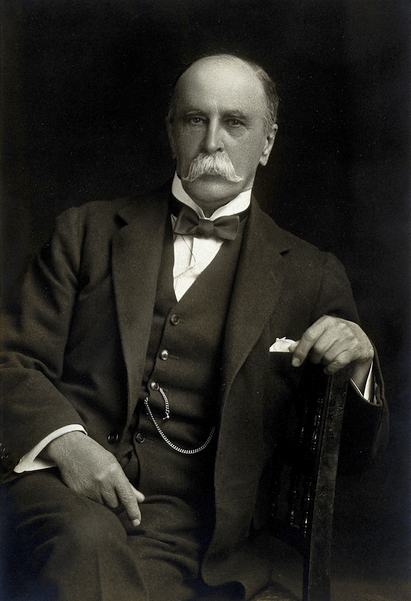

Until quite recently, the practice of medicine was considered an art, which incorporated a significant modicum of science, yet was itself not a pure and applied science, such as physics, astronomy, biology, and chemistry. Sir William Osler (1849-1919), one of the greatest medical minds, not only in the science of medicine, but more so the art of medicine, has written:

What, after all, is education but a subtle, slowly-affected change, due to the action upon us of Externals; of the written record of the great minds of all ages, of the beautiful and harmonious surroundings of nature and of art, and of the lives, good or ill, of our fellows—these alone educate us, these alone mould the developing minds.[1]

It used to be accepted that the aim of medical education was to produce physicians that would be well rounded, not only in the particulars of their specialty, but also as members of a cultured and intellectually engaged society of men—men who could think critically and with a depth that brings wisdom. Dr. Osler recognized that medical education was a complex insertion of “varied influences of art, the highest development of which can come only with that sustaining love for ideas which ‘burns bright or dim as each are mirrors of the fire for which all thirst.’ ”[1]

In an essay on medical education, Osler goes into great detail as to what is necessary to train a young medical student in the “art of medicine.” He points out that in the “old days” a medical student was nothing more than an apprentice who worked with a seasoned physician. Yet, through their close association, the elder physician was quite adept in teaching his art to the young student, not just by depending on textbooks and rote memorization, but also by carefully studying people suffering from a variety of diseases. I emphasize “people,” since so often, especially among specialists and the young physician, the human aspect of what we do escapes them.

I can remember in medical school we were told that our assigned patients were not the “gallbladder in bed 17” or the “adenocarcinoma of the breast in ward three.” Rather, they were human beings—somebody’s mother, or brother, or son. They had feelings and fears, just as we did. As a result, I got in the habit of always thinking of my patients from the viewpoint of either being myself or a member of my family and it helped keep me more empathetic.

Of great concern to Osler was how the art of medicine would be taught. He states:

Ask any physician of twenty years’ standing how he has become proficient in his art, and he will reply, by constant contact with disease; and he will add that the medicine that he learned in the schools was totally different from the medicine at the bedside.[1]

As a consequence, Osler says:

Teach him how to observe, give him plenty of facts to observe, and the lessons will come out of the facts themselves. …The whole art of medicine is in observation, as the old motto goes, but to educate the eye to see, the ear to hear, and the finger to feel takes time, and makes a beginning, to start man on the right path, is all that we can do. …Give him good methods and a proper point of view, and all other things will be added as his experience grows.[1]

This is the antithesis of what is taught today. Because of the rise of scientism, that is science as a religious faith, medical students are taught to rely on their technology and “hard” science. To the modern physician, every statement must be supported by accepted double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, crossover studies ad nauseam. This is so deeply ingrained in our medical professionals, that they cannot bring themselves to believe what their experience demonstrates to them, often in shocking displays.

For example, I have advised a number of people on natural ways to treat their cancers. Most have been under the care of a “traditional” oncologist, usually receiving chemotherapy and/or radiation. In one case I remember very well, a patient was being treated at one of the quite famous cancer treatment centers and when she returned for her follow-up visit, her oncologist was quite surprised to see that not only was she feeling very well, but her metastatic tumors were shrinking significantly. He exclaimed to her that in his thirty years of practice he had never seen a tumor of her type respond so well.

The interesting part is that when she told him what she was doing with her nutrition, he just shrugged and said, “I don’t want to know what you are doing, just keep doing it.” And this is one of the more positive responses. Most take on a look of shock, as if they just sat on a tack, and angrily tell the patient that they should stop immediately because the antioxidants might interfere with their treatment.

In both cases we see just the opposite spirit Dr. Osler was discussing. Despite the fact that neither oncologist had ever seen his patients respond so well to the chemotherapy, it in no way interested either of them that the addition of selected supplements and dietary changes had greatly improved the tumor response. It has been said that it is the anomalies of medicine (and of all natural sciences) that lead to new discoveries. Virtually every great advance in medicine was by men (and women) who noticed something all others had overlooked. That is, because of regimentation of thought and the power of the preconceived notion they were overlooked.

As humans, we tend to think that all discoveries have already been discovered, or will be discovered by the abstract “great minds.” We tend to think of the discoverer as some distant (always distant) person, who is essentially beyond our intellect and possess powers of observation almost god-like. In fact, ordinary men, who, through sharpened powers of observation and deep thinking, saw what escaped others, even the so-called giants of the profession, and made many of our greatest discoveries.

The Case of Dr. Barry Marshall and Dr. Robin Warren

While many examples abound in scientific and medical history, there is one contemporary example that is most instructive—that of Dr. Barry Marshall. Dr. Marshall, like all great discoverers, was a keen observer and listener. Another medical iconoclast, Dr. Robin Warren, in the 1980s in fact suggested the link between an infectious organism and stomach ulcers. A pathologist, Dr. Warren observed that stomach specimens from patients with inflammatory stomach disorders, including peptic ulcer disease, frequently contained a microbe, later identified as helicobacter pylori.[2]

Dr. Warren tried to inform his colleagues about this connection, but they instead made him the butt of their jokes. After all, I am sure they concluded, how could some obscure, local pathologist from Perth, Australia solve the riddle of stomach ulcers when the best experts in the world concluded otherwise.

Dr. Barry Marshall didn’t laugh; instead he listened and conducted carefully controlled experiments to see if Dr. Warren was correct. His evidence should have convinced anyone, but the power of the preconceived notion, especially one that emanates from the elite members of the medical establishment, is a very difficult thing to overcome.

As occurs so commonly in our modern world, Dr. Marshall had great difficulty overcoming the reticence of the medical establishment to at least give him a respectful audience. His articles were rejected by the major gastroenterology journals and he was refused an audience at respected gastroenterology meetings. Except for his dogged determination, as admitted by his friend Dr. Warren, the theory would never have seen the light of day, which even then took 10 years.

It was only through one influential doctor’s assistance that Marshall was given the audience he sought; the rest, as they say, is history. Yet, that is not the end of the story. In 2005, Dr. Marshall and Dr. Warren shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for their discovery. Today, there are thousands of articles confirming their findings and we now know that this same organism is linked to cancer of the stomach and possibly atherosclerosis.

There are several lessons to learn from this sordid episode other than the obvious one—that is, the medical elite’s resistance to ideas outside its control. First, Dr. Marshall himself admitted that his training in medical school left him with the impression that “everything had already been discovered in medicine.” Most of us who attended medical training were given this same impression, that we were just ordinary “doctors” and that only the elite within the medical centers held sufficient intellect to formulate meaningful discoveries, and then only from the “chosen medical centers.”

One of the other lessons is that in most areas of medicine today there are powerful, most often financial, forces that have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. One of these forces is the entrenched elite of the medical world, usually subdivided among each of the specialties of medicine. In the case of Drs. Marshall and Warren, it was the gastroenterologists.

There are personal reasons to consider as well. To have spent one’s life in the study of a particular problem and arrived at no new discoveries is painful enough, but to have some young upstart suddenly appear on the scene proclaiming to have the “answer” is especially disconcerting to those holding prestigious positions.

A second, less obvious force to the casual observer is the financial influence maintaining rigidity in medicine. The pharmaceutical companies were making a fortune in selling antacid medications for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Cimetidine (Tagamet) and ranitidine (Zantac) were the leading ulcer medications at the time and to the CEO makers of these medications, they were the dream drugs of the industry—primarily because they did not cure ulcers and therefore required a lifetime of the medication.

The largest pharmaceutical companies are major funding institutions of research in the medical centers, especially the more influential medical centers. Consequently, the leaders of specialty societies are often financially connected to the pharmaceutical manufacturers, which, in turn, affect their decision-making, both consciously and subconsciously. Even the ethically centered physician will come under this influence. It took me a long time to admit this myself when I was practicing neurosurgery.

When pharmaceutical detail men and women are giving you abundant supplies of free medications for your office, treating you and your staff to lunches and office parties, and offering free trips to meetings in exotic places, one has a propensity to, even subconsciously, yield to their influence. Why else would pharmaceutical companies spend billions on such programs to influence doctors prescribing habits?

Drug detail personnel used to be mostly men. Yet, over time they found it very difficult to get appointments to see the doctor. Quickly catching on, the pharmaceutical companies began to hire women, mostly young, very attractive women. It worked like a charm; suddenly doctors made time to see the pretty drug representative.

Medical history is littered with such episodes, yet we learn nothing. I like to say that the medical profession’s learning curve is a flat line. As Arthur Schopenhauer’s (1788-1860) disputed assertion, accurately epitomizes, “Every truth passes through three stages before it is recognized. In the first, it is ridiculed, in the second it is opposed, in the third it is regarded as self-evident.”[3]

What Medical Education Should Teach

The arrival of science as the preeminent mode of understanding the universe can be traced to the 18th and 19th centuries with Paris being its center, according to F.A. Hayek in his magnificent book, The Counter-Revolution of Science.[4] Growing from logical positivism, science became imbued with its power and became resentful towards those it envisioned to be its enemies, primarily in the areas of theology and metaphysics. This is despite the fact that, as many have observed, science owes its very existence to theological ruminations of ancient Greek philosophers and in Genesis of the Old Testament, stemming from the idea the universe is an ordered and logical creation.

Over time, scientists become convinced that their view of the universe was not only the most accurate, but also the only one that should be allowed. This tendency of a discipline to demand that its intellectual competitors yield the public forum is legendary. Many today are of the opinion that if something cannot be verified by the scientific method, it is not to be accepted as valid and should be labeled as speculation or worse (in their lexicon), a superstition.

Wiser men of science have long recognized that there are things in this universe that cannot be understood by utilizing a scientific viewpoint or discovered only by using the scientific method, that is, that they understood that science can only tell us about material phenomena or forces that have a repetitive nature, which then lend themselves to examination and measurement utilizing the scientific method. In fact, outside the realm of science there exist a tremendous number of phenomena that will remain unknown and that contain many secrets that only God can know.

Early educators of physicians knew this very well and accepted that the best man could do was use his powers of observation to approximate the truth as closely as possible to the prediction of reality. Medical history teaches us that often times we can effect treatments based on little knowledge of underlying mechanisms. For example, 100 years ago herbalist didn’t know why hawthorne lowered blood pressure and made people with “dropsy” (heart failure) do better, yet it still saved hundreds of thousands from a life of suffering and early death. Only now do we understand the “science” behind this early observation.

Today we have turned it around—i.e., treatments are not to be used, despite demonstrated usefulness and ability to save lives, until we have a scientific explanation as to how it works and proof-positive double-blind, placebo controlled studies proving that it is efficacious. I would wager to say that millions are dying every year because of this worship of the scientific method and imagined scientific purity.

Dr. Osler hints at the danger of this narrow-minded view of medicine by his advice to the medical student:

The hardest conviction to get into the mind of a beginner is that the education upon which he is engaged is not a college course, not a medical course, but a life course, for which the work of a few years under teachers is but a preparation. Education is a life-long process.[5]

Further he says that the student must have an “absorbing desire to know the truth, and unswerving steadfastness in its pursuit, and an open, honest heart, free from suspicion, guile and jealousy.”[6] Yet, most graduates of medical schools and residency programs are not given this valuable advice, rather they are told that the elite of medicine will inform them of what they need to know and how they will treat their patients, and do so by a series of preconceived prescriptions.

This becomes especially frightening when you consider the mindset of the elite in medicine already elucidated above—i.e., that nothing is true until “our” science says it is true. The bodies continue to pile up while we are told to wait patiently for their anointed approval to magically appear.

The Origin and Modern Appearance of Regimentation in Medicine

As with most ideas making their appearance as “new” and ”progressive,” regimentation of society is not new. Writers and philosophers from antiquity toyed with the idea of a structured and a centrally ordered society, but it was not until the arrival of the gnostic prophets of the Enlightenment philosophies of Helvetius, Comte, Turgot, d’Alembert and later Marx and Lenin that we observe the development of this philosophy of collectivism. For an excellent analysis of the modern positivist ideology, I would suggest Eric Voegelin’s book From Enlightenment to Revolution.[7]

Another great thinker, Richard Weaver, has crystallized for us the modern dilemma:

The modern knower may be compared to an inebriate who, as he senses his loss of balance, endeavors to save himself by fixing tenaciously upon certain details and thus affords the familiar exhibition of positiveness and arbitrariness. With the world about him beginning to heave, he grasps at something that will come within a limited perception. So the scientist, having lost hold upon organic reality, clings the more firmly to his discovered facts, hoping that salvation lies in what can be objectively verified.[8]

In essence, he is saying the scientist, because he has abandoned true understanding and wisdom, must concentrate his efforts with greater tenacity upon what he does best, and that is to break the material world into smaller and smaller pieces, never quite seeing even a glimpse of the whole. This is exactly what medicine has done with its inordinate divisions of its science into smaller and smaller degrees of subspecialization. As Osler has observed, the man of medicine must be much more than science and textbooks, he has to have an intuitive sense of the effects of disease upon the whole human being and be able to respond to that intuitive sense appropriately, that is, with a certain degree of extra-scientific understanding based on reason and spirituality. In essence, we must not see our patients as merely part of a collective, but rather as individuals—mysterious and incompletely understood.

It has been the contamination of past generations, primarily by prophets of positivism and the levelers (appropriately characterized as egalitarians), who have infected medicine with this collectivist worldview. In essence, this view expresses the idea that man should have a uniform existence, and in the case of intellectual pursuits, one opinion. To the collectivist, there is no such thing as objective truth, one must rely rather on the wisdom of the elites to bring us approximations and declared truth. It is in their positions as “anointed experts” that they receive their authority.

William Blake observed in his prophetic poem Tiriel: “One law for the lion and the ox is oppressive.” Yet, this is exactly where we are moving in medicine, as well as the rest of society. Uniformity has taken the name of “evidence-based medicine,” which implies that the self-appointed elites’ prescriptions for diagnosis, disease classification, and treatments are the final word on the matter— that is, all questions have been answered, and no further discussions from below are needed. Dissent, we are told, is useless, as it would be in arguing against, say, a mathematical principle or the law of gravity itself.

I have heard a number of doctors remark—how can you argue with the science? Scientific pronouncements have become the final arbiter of all disputes, the court of last resort. This is because of the preconceived idea that science deals purely in “facts,” not opinions. Yet, anyone familiar with scientists know this just isn’t true. Subjectivity flows through most of science, and could not be otherwise, since human beings are doing the science. A number of subconscious prejudices infiltrate their way into even the most honest and forthright of scientists. We want to see our theories and ideas prevail over our intellectual competitors, even if subconsciously this affects our conclusions and worldview.

Again, we must not lose sight of the most powerful of the corrupters of man—the love of money. An old Spanish proverb states that “money and honor are seldom found in the same pocket.” Money seeks the ones who have the greatest influence, and in medicine that is the elite, primarily those in the halls of academia and sitting on controlling boards of specialty societies. A number of studies and investigations have shown that elite members of the boards controlling standards of treatments, such as vaccine boards, are often populated by those receiving remunerative rewards from the pharmaceutical companies.

Whatever the impulse—whether a desire for power, arrogance, financial reward, or a true belief that what they are doing is correct and beneficial for society—the risk of widespread harm is always present, because it institutionalizes their ideas and punishes competing ideas. In essence, it demands obedience.

With the idea of “evidence-based medicine” being the final word, dissenting doctors are treated as charlatans and as a danger to society. Likewise, the very name—i.e., “evidence-based medicine”—implies that dissenting viewpoints are not based on the evidence. What we often see is the refusal to accept the evidence of those outside the orthodoxy, no matter how strong. With the elite controlling the definition of what constitutes “evidence,” their intellectual competitors find themselves in an untenable position, often expressed as heads, I win; tails, you loose.

Whose Evidence?

One must appreciate that there exists all kinds and degrees of evidence in medicine. To eliminate the competition, all that is necessary is to make the evidence so stringent that the opposition can never meet the requirements for proof. I find it ironic that in most cases the orthodoxy insists on the weakest form of evidence, but the form most subject to manipulation—that is, the epidemiological study. Most statisticians agree that this is the weakest type of study.

What astounds, for example in the case of cancer studies, is that evidence based on an assortment of types of studies—in vitro, a variety of in vivo animal experiments and even human experience, can show powerful evidence of effectiveness, yet the proposed treatment is still rejected on the flimsiest of excuses.

For example, curcumin may show a powerful ability to suppress a number of cancer types in cell cultures of human cancers in doses easily attainable in humans, yet the evidence is rejected. Sometimes based on good reasoning, sometimes not. In the case of in vivo evidence, they might state that the effect could be species specific, which is certainly true. When repeated in a number of species, they are still not satisfied.

Later, an abundance of studies clearly demonstrate the exact mechanism of curcumin’s effect on cancer cells, that is by dissecting out its effects on critical enzyme systems and cell signaling systems required by the cancer. Still it is rejected. One can show that the product in question has no toxicity and a wide margin of safety, still to no avail.

One of the dreams of the chemotherapists has been a drug that only attacks the cancer cells and not normal, rapidly dividing cells; something called the “magic bullet.” Curcumin, as well as a number of other nutrients, have shown this property. Yet, it can do something far beyond this; it has been shown in a number of studies to protect normal, rapidly dividing cells against the toxicity of most chemotherapy agents, especially those associated with the highest incidence of serious side effects. Despite this, we see absolutely no interest among practicing oncologists, despite much interest among cancer researchers. Remember, curcumin has essentially no toxicity and has never been shown to interfere with conventional treatments. Even more astounding, it can significantly enhance the effectiveness of conventional treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Again, we find ourselves revisiting the case of Dr. Barry Marshall. In essence, we have overwhelming evidence from a multitude of studies that some nutrients can dramatically reduce the growth, spread, and lethality of a large number of cancers, yet it is met with overwhelming opposition.

In seeking an answer as to why this should be so, I do not accept the commonly heard answer from the lay public—namely, that doctors do not want to cure cancer because it is a big moneymaker. The average practicing doctor, because of regimentation, has been conditioned to accept the treatment protocols of the elite, mostly in their respective specialty societies. They are what have been called in political philosophy, “true believers”—that is, they trust the elite, and hence, many truly believe in what they are doing.

Osler warned his students to “get accustomed to test all sorts of book problems and statements yourself, and take little as possible on trust.”[6] I have witnessed a number of doctors who trust only a handful of journals, most often of which includes the New England Journal of Medicine. Outside of this narrow range of approved topics and reading material, they read very little. I am puzzled by this thinking. One must ask, “How could they assume that of the tens of thousands of studies reported in thousands of high-quality journals, only the studies within 3 or 4 journals are worthy of reflection and application to their patients’ care”?

Another defect we have in medical education is that doctors know little about critically analyzing journal articles and studies. Some are quite adept, but many are no better than the layman. Many read only the abstract of an article and others only the discussion or conclusion. A number of respected scientists have observed that many scientific articles contain conclusions that do not match their data. I have seen this many times. Yet, it is the conclusion that many doctors and virtually all of the media cling to and quote at their own peril.

Manipulation of Words and the Power of Propaganda

Richard Weaver, one of the greatest students of human language in the 20th century, notes in his masterful book, Language is Sermonic, that certain words are almost “god-like” (he used the label “god-term”) in their position among the mass of words used in human communications. That is, they convey a sense of such absolute goodness and unassailable truth that no one ever questions their authority. These include the words “progress” or “progressive,” “science,” “fact,” and “efficient.” He notes, “There is no word whose power to move is more implicitly trusted than “progressive.”[9]

Rarely is it that anyone, even among the most analytical intellectual, questions something that is referred to as “progressive.” This isolates the idea as sacrosanct. It is as though the use of this “god-term” protects the idea from further analysis and signals that all further discussion must extend from this basic understanding. This is how societies have come to accept collectivism; it was anointed as “progressive.”

Another “god-term” is “science.” We often hear the phrases: “The science says…” or “The science convinces us that…” which are meant to convey to us the matter is settled. This brings us to the next “god-term,” which is “fact.” Science, we are told, is closer to truth because it is based on “facts,” which are provable by a method called, most appropriately, the scientific method.

A “fact” implies to us or at least is understood as meaning something that is beyond dispute—accepted by all rational minds. Weaver tells us that the word “fact” was inserted into our language during the Renaissance, based on the rise of the scientific method as the new mode of arriving at verification of truth. Prior to this time, truth was derived from either divine revelation or a use of dialectics, that is, the use of logical laws and reason. One must appreciate that despite much assurance from the collectivists, these sources of knowledge have not been discredited.

Like “science,” they inform us one does not argue with the “facts.” Weaver makes a very important observation. He notes, “Possibly it should be pointed out that his ‘facts’ are frequently not facts at all in the etymological sense; often they will be deductions several steps removed from simply factual data.” We see this commonly in our modern, progressive society.

Take for example the often-quoted “fact” that statin drugs prevent heart attacks by lowering cholesterol levels. This statement is not a “fact” at all but an assumption based on a cleaver manipulation of data. In fact, the “data” in no way supports such a broad statement, and likewise, there is no hard evidence elevated cholesterol causes heart attacks and strokes. Yet, most physicians repeat this mantra as if it was established fact, that only a fool or charlatan would deny. In essence, the case is closed to further discussion. All future discussions are to emanate from this established “fact.”

We see similar examples throughout much of what is accepted as “evidence-based medicine.” The danger of using words to justify constricting inquiry is that soon the accepted idea becomes institutionalized merely on the fact that the elite have anointed it. This sets the stage for a transition from voluntary acceptance to compulsion by the State or the medical societies. Physicians will, in essence, accept the dogma or, like heretics, they will be excommunicated from the profession, since the elite making the rules also control their licenses.

We must understand when the State takes over the reins of medical care, as it will most assuredly do, offenses against the orthodoxy will be punishable by severe penalties, including jail sentences. We are already witnessing this in the Medicare/Medicaid system, where a number of doctors are serving long prison sentences and massive fines for violating the rules of regimentation of medical care.[10]

In Part II, concluding this essay, we will discuss how regimentation reduces creativity and freedom and fosters other evils of collectivism for which we pay a heavy price in both medicine and society at large.

References

1. Osler W. Aequanimitas: With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Company; 1904, p. 100, 172, 307, 331, 400.

2. Marshall BJ. Chapter 3: One Hundred Years of Discovery and Rediscovery of Helicobacter pylori and Its Association with Peptic Ulcer Disease in Mobley HTL, Mendz GL, Hazell SL, editors. Helicobacter pylori: Physiology and Genetics. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2001.

3. Schopenhauer A. Chemurgic Digest 1951: Vol. 10-11; p. 13.

4. Hayek FA. The Counter-Revolution of Science. Liberty Fund; 1980

5. Osler Society of New York. Available from:

6. William Osler quoted in Bryan CS. Inspirations from a Great Physician. Oxford University Press; 1997, p. 74, 116.

7. Voegelin E. From Enlightenment to Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1975.

8. Weaver R. Ideas Have Consequences. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1948, p. 57.

9. Weaver R. Language is Sermonic. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press; 1985, p. 89.

10. See the Special Issue titled the Police State of Medicine in the Medical Sentinel, July/August 1998.

Written by Russell L. Blaylock, MD

Dr. Russell L. Blaylock is President of Advanced Nutritional Concepts and Theoretical Neurosciences Research, LLC, in Jackson, Mississippi. He has written numerous path-blazing scientific papers and many books, including Excitotoxins: The Taste That Kills (1994), Bioterrorism: How You Can Survive (2001), Health and Nutrition Secrets (2002), and Natural Strategies for Cancer Patients (2003). He is Associate Editor-in-Chief and a Consulting Editor in Basic Neuroscience for Surgical Neurology International (SNI). His websites are: www.blaylockwellnesscenter.com and www.russellblaylockmd.com.

This article can be cited as: Blaylock RL. Regimentation in medicine and the death of creativity (Part 1). HaciendaPublishing.com, March 14, 2015. Available at: https://haciendapublishing.com/regimentation-in-medicine-and-the-death-of-creativity-part-1-by-russell-l-blaylock-md/.

The photographs used to illustrate this article, exclusively edited for Hacienda Publishing, came from a variety of sources and do not appear in earlier, unillustrated versions published elsewhere.

Copyright ©2015 Hacienda Publishing, Inc.