- Articles

Medical History — Plagues and Epidemics by Miguel A. Faria, MD

Note: In view of the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), I find it important for readers to receive background information on public health history, plagues and epidemics, from antiquity to more recent times.The COVID-19 pandemic does not approach the virulence of previous epidemics, and I’ve no doubt that God permitting humanity will conquer with a minimum of casualties. — MAF (March 16, 2020)

Since the fall of the Western Roman Empire, there have been three major bubonic plague epidemics, which afflicted large segments of the population in the continuous Eurasian landmass and North Africa. Death quickly followed the trade routes of the times. The death toll is almost incomprehensible. The Plague of Justinian (6th Century A.D.), the Black Death (14th Century A.D.), and the Bubonic Plague (1665-1666, which coincided with the Great Fire of London) caused an estimated 137 million dead in a world much more sparsely populated than it is today.

To make matters even worse, one must also remember that these pestilences assailed and ravaged mankind at a time when the average life span was short — less than two decades during the Middle Ages. Survival to age five was a miracle not only because of endemic disease, dirt and filth, concomitant poor hygiene and sanitation, but also because of the primitive state of medical knowledge. Pestilential disease thrived under such conditions. Moreover, during the Middle Ages, bathing and cleanliness, even in the upper classes, was a rarity, being viewed as unhealthy as well as irreverent — acts of vanity in the face of God.

Epidemics in the Graeco-Roman World

During the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.), fought between ancient Athens and Sparta and their allies for supremacy of the Greek world, the Athenian army had to withdraw behind the safety of its city walls after a successful invasion was carried out by Spartan forces. Shortly after, in 430 B.C., the historic Athenian Plague broke out decimating a quarter of the population within the city. The supreme Athenian statesman and leader, Pericles (c. 495-429 B.C.), succumbed to this epidemic after seeing his own sister and two sons contract the disease and die. Historians are not completely sure this pestilence was really the plague. It’s possible it was some other disease such as smallpox.

Plague or otherwise, the historian Thucydides left a poignant account of this catastrophic time recounting that the Athenians, “…fear of gods or law of men there was none to restrain them. As for the first, they judged it to be just the same whether they worshipped them or not, as they saw all alike perishing; and as for the latter, no one expected to live to be brought to trial for his offences.” The historians Frederick F. Cartwright and Michael D. Biddiss in their book, Disease and History, added that Thucydides lamented that “the most staid and respectable citizens devoted themselves to nothing but gluttony, drunkenness and licentiousness.”(1)

Likewise, during the reign of the great Stoic philosopher, the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (emperor, AD 161-180), a great pestilence was brought back to Rome (AD 166-167) by the victorious legions which, led by Lucius Verus (co-emperor, AD 161-169), had been pushing back the invading Parthians pressing on the eastern frontiers of the empire. This pestilence caused the death of approximately 25 million people and was most likely smallpox. Co-emperor Lucius Verus was eventually afflicted and, like Pericles nearly six centuries earlier, succumbed to the disease. One can only imagine the devastation of these epidemics in the midst of wars: the loss of loved ones; the breakdown of societal, civic and learning institutions; the breakdown of law and order, particularly in the countryside where the population was at the mercy of barbarian hordes and brigands; goods not produced; services not rendered; lands not cultivated; crops left unharvested, etc.

The Plagues of the Middle Ages

At the peak of his reign, after accomplishing major political, judicial, and military successes, Justinian, emperor of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, suddenly faced an old, ferocious enemy of mankind: pestilence. The bubonic plague, which struck in A.D. 540, is justifiably the worst recorded pandemic to ever afflict humanity. Any hopes of reestablishing the Roman Empire were dashed. Records regarding the dimensions of the devastation and the untold suffering and death were carefully kept by Justinian’s chief archivist and secretary, the celebrated court historian, Procopius.

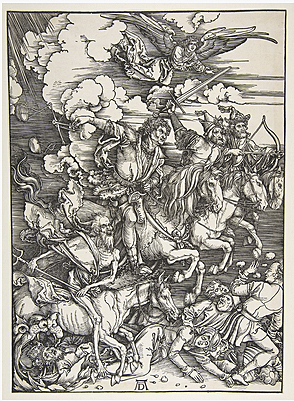

If one considers the dimensions of the devastation of the bubonic plague of the 6th Century in the midst of the Dark Ages — the savage imperial wars waged against the barbarian hordes, the terrible famines, the ubiquity of death and destruction, and finally the unleashing of this cataclysmic epidemic — it should not be difficult to imagine that the people at the time believed that they were being scorched and ravaged by the dreaded Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as described in the biblical book of Revelation 6:8, “And I looked, and behold, a pale horse; and his name that sat on him was Death.”

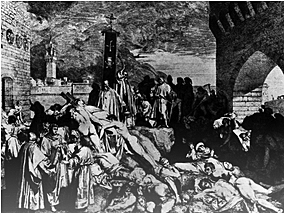

The Emperor Justinian, defeated by the cataclysm of the bubonic plague, saw with horror the disease demolishing his once invincible armies and killing his generals and soldiery alike faster than the wounds inflicted on the battlefield. Entire villages and towns were obliterated; the apocalyptic visitations were considered divine retribution from God as punishment for worldly sins. Demoralized and disheartened, he returned to his capital, Constantinople, only to find that there, too, the terrifying pestilence was relentlessly killing his people, rich and poor, regardless of kinship or station in life. The mortality in the city at this time was approaching 5000 deaths a day and would eventually reach an all-time high of 10,000 deaths daily. In despair and in need to fill the void, Justinian sought solitude, and the comfort and solace of religion.

The learned physicians of Justinian’s day, who at the time followed the precepts of Graeco-Roman medicine, were discredited because their nostrums proved useless at the time of the cataclysm. Instead, the people turned for consolation to monastic medicine and the teachings of Christianity. The Christian church did rush in and, as best it could, tried to fill in the medical void. The monks in the monasteries quickly became the spiritual as well as corporeal healers by tending both to the needs of the soul and the requirements of the body. They used prayer and only the rudiments of physical or herbal medicine to console and heal the sick.

The humbling of the medical profession because of its impotence to control the plague of the 6th Century, essentially halted the advancement of medical knowledge for centuries. Medicine regressed, and disease in general was equated with vice and sin, rather than with filth, poor hygiene, and natural causes.

Yet, medicine was not the only profession in abeyance to disease. Other ancient professions, such as law, engineering, and the natural sciences (not to mention the liberal arts of the Greeks and Romans), were largely erased from the collective memory of humanity. All areas of human endeavor were doomed to intellectual dormancy. Progress stopped. The turning wheels of Western culture and civilization had ground to a shrilling halt as humanity became fully immersed in the Dark Ages. New hordes of barbarians were marauding and ravaging the West, while the plague was humbling the East.(2)

The great pestilence of the medieval period was the Black Death (1346-1361), the bubonic plague caused by the then highly virulent bacterium, Pasteurella pestis and transmitted generally by the black rat, Rattus rattus. The plague is passed from rat to rat by fleas. Man becomes infected when he unwittingly interrupts the infectious cycle by being bitten by an infected flea. Once the infection takes place, Pasteurella pestis causes disease by septicemia or by invasion of the lymphatics, spreading in the body with two types of presentations. The pneumonic form of the plague is most ominous. In this highly contagious acute form, the disease may also be transmitted directly from person to person via the pulmonary route (i.e., aerosol droplets), and death takes place rapidly. It was said that one day a person would cough-up phlegm and then be dead by the fifth day.

The predominant form of the disease, though, was the subacute bubonic form, characterized by severe involvement of the lymphatic system with the formation of buboes (from which the disease takes its name). The buboes are swollen, infected lymph nodes, most commonly involving the inguinal and/or the auxillary lymph node chains. The buboes may grow to a significant size to erode through the skin and spontaneously burst, draining infectious purulent material. Death came in a slower and more agonizing way. Very few so afflicted lived beyond 10 days, and the affliction still carried a mortality of 90 percent.

The epidemics of bubonic plague were veritably history’s greatest scourges. In the case of the Plague of Justinian, the epidemic ravaged the populace for five decades between A.D. 540 and 590 and, although precise figures are not possible to ascertain, it may have caused the death of one-third of the population. The Black Death, which peaked in 1347-1348, also inflicted morbid devastation and rampant desolation and death in medieval Europe and exacted a death toll of perhaps 27 million lives and lasted 15 to 20 years. The Black Death seriously disrupted the social and economic fabrics of Western society. In Europe, the people began to question religion and faith and looked instead for answers in the emerging science of the medieval universities sprouting up throughout Europe, the reverse of what took place after the Plague of Justinian. Moreover in England, large tracts of land were left uncultivated because of the lack of a work force. Suddenly, labor because precious. Workers demanded higher wages and poor peasants disappeared, at least for a time, and were replaced by more prosperous farmers and landowners, threatening the very structure of feudal society.

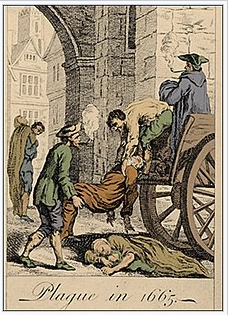

The Great Plague of London, which assailed England from 1665 to 1666, at its peak killed 2000 Londoners a week but mercifully only lasted several months, coincidentally ending with the Great Fire of London.

The New World and Disease

With the discovery of the New World in 1492, infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox were brought to the New World, wreaking havoc in the immunologically susceptible indigenous population. In return, the Europeans carried syphilis back to their homelands. Recently, there have been accusations of European genocide upon native populations of the New World. But, as the author wrote in Vandals at the Gates of Medicine: “This depopulation [of the Americas] was neither officially sanctioned, anticipated, or even intended by the Spanish or Portuguese authorities. These afflictions had more to do with the mingling of two very different and isolated cultures (which up to this time had not been in contact with each other) than with a deliberate act of genocide.”(2)

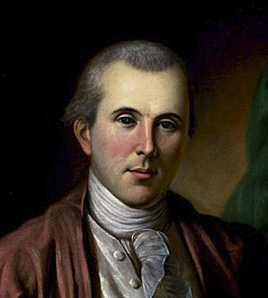

In 1647, yellow fever appeared in the colony of Massachusetts assailing the population and killing many inhabitants. To prevent further spread of the disease, quarantine was implemented for the first time in the colonies. In 1665, the quarantine was extended to all ships coming from England to prevent spread of the bubonic plague that was then assailing London. In the eighteenth century, yellow fever reappeared in Philadelphia, particularly in 1793, decimating the population of that city. It is estimated that ten percent of the population died, and according to medical historian Howard W. Haggard, in his book the Doctor in History, “Philadelphia resembled London in the days of the bubonic plague.”(3) Many people fled the city but one doctor who stayed was Dr. Benjamin Rush, an American patriot and one of three physicians who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Dr. Rush indefatigably ministered to the sick with the treatments of the time, purging and bleeding, and became a popular hero.

Humorous medical historian, Art Newman, in his book The Illustrated Treasury of Medical Curiosa, described one such occasion: “[Dr. Rush’s] coach was stopped at Kensington by a crowd of hundreds who begged him to visit their homes and care for their sick. Rush stood up in his curricle and addressed the throng. ‘I treat my patients successfully by bloodletting and copious purging with calomel and jalop, and I advise you, my good friends, to use the same remedies.’ Someone shouted, ‘What, bleed and purge everyone?’ ‘Yes!’ cried the doctor. ‘Bleed and purge all Kensington!’ “(4)

The Final Act in the Drama

The first case of cholera occurred in England in 1831. No explanation can be offered for why cholera, which had been confined to India as an endemic disease for at least 2000 years, suddenly burst forth as a worldwide affliction. We do know that up to the mid-nineteenth century, European cities were reservoirs of disease because of the ubiquity of dirt and filth and poor hygiene and sanitation. Newman recalled: “Down the middle of English streets ran a gutter or kennel into which garbage and refuse were tossed to fester in the hot sun”; and the great Anglo-Irish writer and satirist Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) parodied: “Now from all parts the swelling kennels flow, And bear their trophies with them as they go; Filths of all hues and odours seem to tell/ What street they sailed from by their sight and smell”(4)

Cholera reached New York in 1832 and subsequently spread to Mexico, Cuba, and the rest of the Americas. Credit should be given to the great English physician from Newcastle upon Tyne, Dr. John Snow, whose work solved the problem of the transmission and prevention of cholera in 1849. A fine anesthesiologist and epidemiologist, Dr. Snow proved by scientific investigation that cholera is a water-borne disease, his research eventually led to the conquest of such epidemic diseases as dysentery and typhoid fever.

Snow’s epidemiological studies were momentous discoveries, but they needed to be applied by his successors. Consider that still in the Spanish-American War (1898), the U.S. lost more soldiers to typhoid fever than were killed in the battlefields of Cuba and the Philippines.

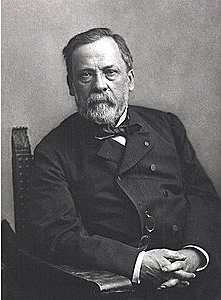

In 1885, the French scientist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) established a clear relationship between microorganisms and disease, formulated and proposed the fundamental principles of the germ theory of disease, and ended the vicious cycle of superstition, ignorance and disease. Pasteur finally demolished and put to rest the old theory of spontaneous generation that had held medicine back for centuries by convincingly demonstrating that living microbes caused not only fermentation but also putrefaction and disease.

It was Pasteur’s systematized observations and experiments that clearly rejected the theory of spontaneous generation, which had dictated that disease arose from non-living things such as miasmas from marshes rather than living microbes.

The germ theory of disease was the Achilles heel of those old, furious enemies of humanity — plagues and epidemics. Once scientific theory was put into practice with improved hygiene and sanitation, disinfection, and the use of antibiotics — the old bacterial enemy was largely vanquished.(5)

Yet, infectious disease has not been eradicated. In modern times, the Influenza Epidemic of 1918 suddenly erupted and unmercifully killed 20 million people. Of those who survived, many later suffered unusual sequelae, such as atypical Parkinson’s disease.

Thus, enemies of humanity, like viruses (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] that causes AIDS), some protozoa (e.g., malaria, toxoplasmosis, etc.) and even infective particles made up of nucleic acids (i.e., DNA and RNA) and/or proteins, such as prions which are posited to cause such dreadful diseases as Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease and Mad Cow Disease — are yet to be subdued. Medicine still has a lot of work to do in the struggle of humanity against epidemic illness, disease, and pestilence.

Read: Medical History — Hygiene and Sanitation

References

1. Cartwright FF, Biddiss MD. Disease and History. New York, NY, Dorset Press, 1991, pp. 29-53, 113-166.

2. Faria MA Jr. Vandals at the Gates of Medicine: Historic Perspectives on the Battle Over Health Care Reform. Macon, GA, Hacienda Publishing, Inc., 1995, pp. 161-165.

3. Haggard HW. The Doctor in History. New York, NY, Dorset Press, 1989.

4. Newman A. The Illustrated Treasury of Medical Curiosa. New York, NY, McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1988.

5. Williams G. The Age of Miracles: Medicine and Science in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago, IL, Academy Chicago Publishers, 1987.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Editor emeritus of the Medical Sentinel of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS), https://haciendapublishing.com. This article on the history of medicine is excerpted in part from Dr. Faria’s Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995) and Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997). Copyright ©2002 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Medical History — Plagues and Epidemics. HaciendaPublishing.com, March 16, 2020. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/medical-history-plagues-and-epidemics-by-miguel-a-faria-md/

Originally published in the Medical Sentinel 2002;7(4):119-121. The photographs used to illustrate this article came from a variety of sources and did not appear in the original Medical Sentinel article. They were added here for the enjoyment of our readers.

Copyright ©2002-2020 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Medical History — Plagues and Epidemics by Miguel A. Faria, MD”

Another consequence of the Black Death: The Peasants’ Revolt, (May 30,1381) By Jesús Vico and Beatriz Camino.

On this day in 1381, the introduction of a poll tax led to the outbreak of the Peasants’ Revolt, also known as the Great Rising. It was a largely unsuccessful uprising that took place in late-medieval England. Even though it failed, it served as proof that peasants could be a potential opposition to the monarchy.

Causes of the Revolt —The Peasants’ Revolt was caused by several factors that led to social unrest. To begin with, the Black Death, a pandemic ocurring in Europe from 1346 to 1353, resulted in an economic and social shock for the country. In the United Kingdom, up to a third of the population died resulting in a shortage of labour. As a consequence, wages went up and the landowners put pressure on the government so that they would go back to the level they were before the pandemic. On the other hand, England declared war on France in 1337, during King Edward III’s reign. However, when the King passed away that same year his son King Richard II ascended to the throne and the war carried on. Since he was too young to rule England was governed by his uncle, John of Gaunt, who decided to raise Poll Taxes to be able to collect funds for the war. Still, it was the Poll Tax of 1381 that led to the Revolution. This tax was higher than the previous ones and was paid per person, not per property. As a result, people tried to avoid paying it and the social unrest rose. This unrest was further increased when John Ball, a radical priest, started preaching sermons in which he criticised the feudal system and the Church. He argued that peasants were treated unfairly and encouraged them to demand changes. For that, he was excommunicated in 1366 and imprisoned in April 1381, even though the rebels released him in May of that same year.

The Peasants’ Revolt— The outbreak of the Revolt took place in May 1381. When the King’s Commissioners arrived at Fobbing, a village in Essex, peasants refused to pay and killed them. Soon, the word spread to other villages from Kent and Essex that also joined this opposition. Large crowds started to march toward London and appointed a rebel leader, Wat Tyler. They were further encouraged by John Ball, who told them to demand freedom and greater rights. The protesters burned several buildings and freed prisoners on their way to London. At that time, King Richard’s army was in Scotland and he was forced to seek refuge in the Tower of London. The King, who by that time was only fourteen, eventually met the peasants at Mile End and agreed to their demands. However, shortly after that, they stormed the Tower of London and killed the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor. Then, another meeting took place at Smithfield between the King and Wat Tyler, which resulted in the latter being captured and executed. Afterwards, the King met the crowd of protesters and agreed to abolish serfdom. Most of the peasants left the city and the Revolt was put to an end. Nevertheless, Richard did not keep his promise and did not abolish serfdom Aftermath Shortly after the end of the Revolt, King Richard had all the leaders of the Revolt executed, including John Ball. Even though the rising failed and the protesters didn’t get the demands they were asking for, rules on serfs were relaxed over time. Moreover, a new poll tax was not introduced again until 1990. But most importantly, the Revolt served as a warning that peasants were able to organise themselves in mass numbers and could be a potential opposition to future monarchs.