- Articles

Georges Danton — The Fallen Titan of the French Revolution!

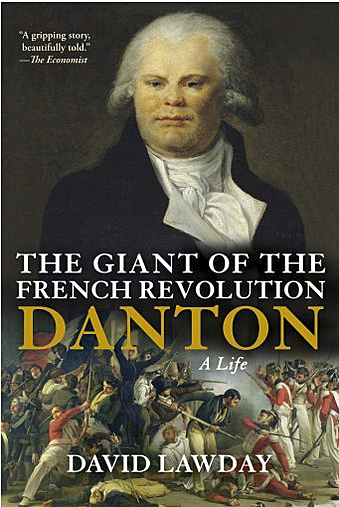

A book review of The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, A Life by David Lawday (2009)

Georges Danton was the “Titan of the French Revolution,” but like the Girondins before him, he was too late in recognizing the need to stop the madness, the grinding of lives by the terror, and the excesses of the Revolution they had unleashed on the hapless French people and, ultimately, the world.

Danton, the man who prepared the Insurrectionary Commune for the storming of the Tuileries in the August 10, 1792 coup d’état; the man who inspired “the Miracle of Valmy” (1792), and the revolution’s greatest orator and hero himself, ultimately became a victim. But Danton went to the guillotine with courage. Retrospectively, Danton had come to his senses too late to stop the terror, the terror he himself had organized in perpetrating (or acquiescing in) the atrocities committed in the unconscionable September Massacres in the tempestuous autumn of 1792. He was never forgiven for these brutalities by Madame Roland, a leader of the great Girondins, who he had fatally opposed. When Danton tried to find allies to stop the terror, there was no one to forge alliances, no counter force left; it was simply too late. Danton and his friends succumbed to the revolutionary monster they had created.

The Committee of Public Safety, headed by his former friend and ally, “the incorruptible” Maximilien Robespierre and his radical blood-thirsty side-kicks, Saint-Just and Couthon, were doing the grinding. By then even many Deputies of the Convention and even some of the other members of the Committee were in fear of their lives.

First, it was the liberal nobility that perished, enticed by the siren song of the philosophes; then it was the moderates, Feulliants; then the Girondins; then the ultra-radical Hébertists, the enragés; then the “indulgents” of the old Cordelier Club led by Danton, Fabre, and Camille Desmoulins; and finally, the Thermidorean reaction brought Robespierre himself and his clique. Like Saturn, the French Revolution devoured its children! But this is the story of Danton, the person, the relationships, the ideals, the revolutionary, the tragedy, and it’s fairly well told.

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out some specific quirks in this book by author David Lawday, who, it must be noted, has fallen deeply in love with his subject Danton, which may be understandable, Danton truly being a greater-than-life revolutionary figure; but Lawday has also been seduced by the betrayed ideals of the sirens of the French Revolution. He compares it (favorably it seems) to the American Revolution and intimates the French ideals achieved a glorious universality that surpassed America’s. In fact, from the very beginning the American Republic was a nation of laws and liberty, unlike the French. Lawday also alludes to the Roman Republic, and so does the subject of his biography, Danton, who had schooled himself on the classics and ancient Roman history and admired their republican institutions. And yet the similarities, as I have said, are highly illusory. The Roman Republic was run by two dozen or so aristocratic families, who for the most part were incredibly capable, proud of their illustrious and often glorious ancestors extending centuries back in history, a military aristocracy that conquered and ruled most of the known Western world. Moreover, the Roman aristocracy did not massacre each other, but formed useful political alliances through marriage and adoptions. I would like to a moment and further digress on another observation I have made on revolutions in general, including the French but not the American — and that is how a person (or persons) playing a a pivotal role often leans and tilts the scale toward the worst side of revolutions.

I refer to Madame Roland’s role in the French tragedy and Cato the Younger’s role in the fall of Republican Rome. There are great philosophic similarities between the revolutionary purity insisted upon by Madame Roland and Cato’s unyielding, stern, and stoic character. Both distrusted and would not accept human failings. Just like the French salonist would not forgive Danton for his alleged corruption and role in the September massacres, Cato distrusted and would not accept the human failings of Pompey the Great. In the case of Cato, Pompey’s true nature and loyalty to the Republic should have been deduced by Cato before it was too late. Cato was indeed correct about Julius Caesar, but not about Pompey, the confident and easy going leader who eventually became the Republican and Senate champion. In the case of Madame Roland, she was entirely correct about the unyielding and villanous Maximilien Robespierre, but Danton, in truth, had become the jovial giant with a relatively good heart who should have been forgiven, cultivated, and enlisted in their cause by the Girondins.

Thus, we have in ancient Rome (49 B.C.), Cato, Pompey the Great, and Julius Caesar; in France (1793), Madame Roland, Danton and Robespierre. Further in time in Russia (1924), the old bolsheviks, Kamenev’s and Zinoviev’s fear of Leon Trotsky’s ambitions led them to support Stalin’s rise to power. In Cuba (1957), American media reporter Herbert Matthews, fell head over heels for Fidel Castro and his 26th of July Movement in the Sierra Maestra, and totally sidelined the anti-communist leaders of the Revolutionary Directorate.

But returning to the book at hand, in The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, A Life, Lawday makes a fairly good case for absolving Danton of having connived in the Duke of Brunswick bribe affair just prior to the Battle of Valmy (1792); but does not do as well in exculpating him from involvement in the horrible September Massacres. Danton is likened to the Comte de Mirabeau, but the latter, the orator of the early Revolution, was much wiser and saw early on the travesty the Revolution was becoming. Mirabeau at least tried to do something in time, may have even been successful, only that he was untimely afflicted with illness and his life cut short before he could have a chance to alter the course of the Revolution, as Talleyrand and Lafayette were to do in the Revolution of 1830.

Lawday also exculpates Danton for his incitation to violence and repeated calls for death to the “enemies of the Revolution” as flowery language. How were the people, the fickle Parisian mobs and the violent sans culottes, always thirsting for savage revenge, to know that Danton’s incitations were “parliamentary theater” and only “figures of speech”? The rabble-rouser Jean Paul Marat and “the Incorruptible” Maximilian Robespierre do get their just deserts in this book; but the Girondins and Royalists are gently maligned as revolutionary snobs and treasonous villains, respectively. Thomas Paine comes out of the pages of this book as a wise Englishman and a political moderate, which, in fact, he was in France at the time. Paine’s relative moderation in the ultra-radical politics of the French Revolution, as opposed to the perceived radicalism in the former American colonies, tells us something, and eerily presages at least in hindsight, about the divergent course of the two revolutions!

The French National Convention, steered by radicals, Lawday calls “weird and wonderful” (p. 146); the August 10 coup d’état led by Danton, manipulating the insurrectionary commune that overturned the fleeting constitutional monarchy, is praised as a patriotic act; of the blood-thirsty prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville, Lawday opines, “it was hard to fault him in his professional endeavors.” Lawday also laments, “it was a pity” that the high intensity of conscription for the levée en masse for total war was resented by the provinces, supposedly because “it intensified the civil war”! (p. 151)

The author perplexed says he cannot fathom why the Girondins, in particular their leader, Madame Roland, felt the way they did about Danton. But the answer is simple: They might not have liked his formidable looks as Lawday suggested, but they certainly did not not like his rabble-rousing harangues, and they certainly blamed him for complicity, if not acquiescence, in the ghastly September Massacres in which 2,500 innocent prisoners were slaughtered in cold blood and the severed head of the gentle Princess Lambelle was savagely paraded on a pike and even shown to her friend, the imprisoned French Queen, Marie Antoinette, in the Temple Tower prison, where she too waited her and her family’s fate.

Yet, Lawday decries Girondin “intractability,” in refusing to make peace with the ultra-radicals and violent Montagnards — an intractability, which he ascribes to Madame Roland’s obsessive personal hatred of Danton. It seems that the author would have been happy if the Girondins had just rolled over and let the Jacobin Montagnards have their way at the Convention. The fact is that with their “intractability” and their refusal to abet the Terror, the Girondins died on the better side of revolutions, and certainly on the better side of history.

In the same light, Lawday writes: “Alas [Prime Minister William] Pitt remained unmoved” regarding Dantons’ peace feelers to Britain, as if Danton’s overtures, coming after the Revolutionary Armies were defeated in the Low Countries and General Dumoriez’s defection, could have been given serious thought. At the same time, Danton was busily calling for total war, “levée en masse,” turning all French male citizens into soldiers, and the Convention was becoming more and more radical and more aggressive in the pursuit of war of Liberation.

In the end, history follows its relentless course: Danton and his friends, Fabre d’Eglantine, Camille (and his innocent wife Lucille) Desmoulins, and the other “indulgents” succumb to the fiendish grinding machine of injustice and terror that they, in particular Danton, helped create. In the case of Danton, the charge is most serious: He instigated the coup of August 10, fomented radicalization of the government, manipulated the mob with his harangues, was complicit in the September Massacres, created the travesty of the Revolutionary Tribunals and ushered in the oppressive Committee of Public Safety — the last two, the ferocious instruments that Maximilien Robespierre handled with superior, ruthless efficiency, and bloody dexterity.

Despite these concerns, I highly recommend this novelistic book with the aforementioned caveats to all readers interested in the French Revolution as well as the course of most modern revolutions since 1789!

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.), Mercer University School of Medicine. Dr. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). Dr Faria has written numerous articles on Stalin, communism, and the Soviet Union, all posted at the author’s website: https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Georges Danton — The Fallen Titan of the French Revolution! HaciendaPublishing.com, June 17, 2014. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/georges-danton–the-fallen-titan-of-the-french-revolution.

(The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, A Life by David Lawday. Grove Press, New York, NY, 2009, 294 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this commentary came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Lawday’s The Giant of the French Revolution: Danton, A Life.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.