- Articles

The Ten Greatest Adventurers in History

Inspired by the incredible adventures of various historical figures and finally spurred on by the book, Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier (2007) by Charles Spencer, which I recently read and reviewed — I have compiled a brief list of arguably the ten most adventuresome characters of history.

Adventuresome here requires an explanation: Audacity in more than one area of historical pursuit in physical adventure, as well as other activities or intellectual pursuits. By this I mean, for example, that charismatic heads of state, such as Robespierre, Mao, Stalin, or Hitler, do not qualify because their rise to power, despotic careers, conquests, and brutal rules are all involved in the same vein — the attainment and preservation of political power. The converse is also true for true republican heroes, who gained power and ruled for the best, such as George Washington and Winston Churchill; or wholly benevolent figures, such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, who belong on humanitarian lists. By the same token, great generals of history, whose virtually sole claim to fame is the result of purely exercising military prowess, such as Napoleon, Hannibal, Alexander the Great, or Scipio Africanus, do not qualify.

The men I list below are those who lived exceptional lives, conducted remarkable adventures, and possibly exerted themselves in multifaceted careers within various fields of interest. Thus, in increasing order of significance, here are the heroes (and possibly anti-heroes) who made it onto my list:

10. Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736) — He was a Prince of the House of Savoy and superlative general who served in the armies of the Holy Roman Empire, virtually during this empire’s last sparks of glory. Not only was he one of the great military commanders of history but, serving with John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough, Prince Eugene stopped the imperialism of the “Sun King,” Louis XIV of France. He led an adventuresome military career and also fought and defeated the Turks, leading successfully the Austrian armies in the War of the Polish succession (1733-1735). A contender for this post would include Don John of Austria, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s illegitimate son and King Philip II of Spain’s step brother and the victor of the decisive Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

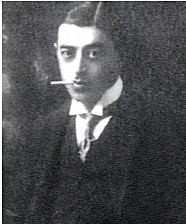

9. Sidney Reilly (1873-1925) — Reilly was a Russian born, English secret agent who fought against the Bolsheviks during the early period of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Reilly worked for Scotland Yard and then MI6 with the journalist-spy Robin Bruce Lockhart and the revolutionary Boris Savinkov, an underground figure of the militant Social Revolutionary Party in Russia, intriguing to overthrow the communist government of Lenin. Before that, Reilly had numerous adventures working, not only as a capitalist entrepreneur, but also as a spy for various nations, yet always remaining loyal to the British. In the end, he was trapped by the Bolsheviks in the “false flag” Operation Trust, conducted by the secret police, Cheka, in which he, like Savinkov, was captured and executed by the communists. He is one of the models Ian Fleming used for the creation of the fictitious character, James Bond. Despite his ultimate failure, Reilly “Ace of Spies” is considered one of the greatest spies of the 20th century.

8. Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) — Cortés was the Spanish conquistador who conquered the Aztec empire in Mexico. Landing in Mexico, he burned his ships to prevent his men from turning back to Cuba and Spain. It was “conquer or die.” Cortés led from the front, was fearless, persistent, and incredibly resourceful. Despite multiple perilous adventures, ambushes, and battles fighting the Aztecs, including the battle of La Noche Triste, and sustaining heavy losses, Cortés triumphed with his handful of conquistadors. With La Malinche as his interpreter and allied with the Tlaxcalans, he ultimately stormed Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, and conquered Mexico. Cortés also explored the northern part of Central America and conquered it. He was made a Marquis by Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, and returned to Spain in 1540 where he died six years later, frustrated and neglected by the Spanish Court, despite his magnificent conquest and the fabulous wealth he attained for Spain.

7. Rodrigo Borgia, Pope Alexander VI (1431-1503) — Rodrigo Borgia was an outstanding figure of the Italian Renaissance and as Pope Alexander VI (1492-1503). He imperiously divided the New World between Portugal and Spain in 1494 with the Treaty of Tordesillas. He presided over the Borgia family, the Spanish-Italian dynasty that included his uncle, Pope Calixtus III; his son, Caesar Borgia; his daughter, Lucretia Borgia; and his kinsman, the saintly priest, Francis Borgia. Pope Alexander VI enriched the papal domains, collected works of art for the Vatican, and augmented the earthly powers of the pope; but he also intrigued, so as to enrich himself and his family at the expense of the spiritual authority of the Church. His only possible contender or runner-up for this spot would be Benedetto Gaetani, later Pope Boniface VIII (1235-1303).

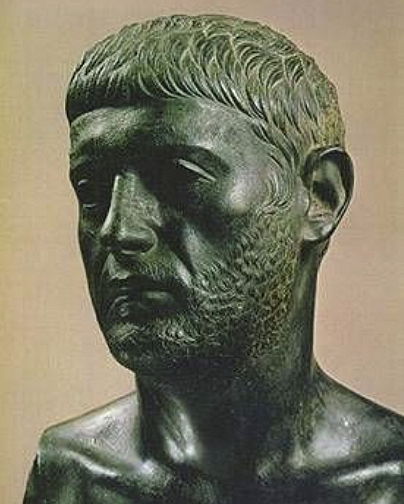

6. Sextus Pompey (67-35 B.C.) — Sextus Pompey was the pious youngest son of Pompey the Great (106-48 B.C.), the Roman general who fought for the Roman Senate against his rival, Julius Caesar. One may ask, why not choose Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, or Pompey the Great rather than his son, Sextus? When Julius Caesar defied the Senate and crossed the Rubicon in 49 B.C., the Pompeians, including Sextus’ father Pompey the Great and older brother Gnaeus, fled to the East to gather their armies and prepared for war. Sextus remained with his step mother Cornelia Metella. After the disaster at Pharsala in 48 B.C., Pompey, Cornelia, and his son were briefly reunited. In Egypt, Sextus and his stepmother watched his father’s assassination. Later, when Sextus came of age, he also joined the remaining Pompeians, now led by Cato and Metellus Pius Scipio in Africa and made his headquarters in Sicily. The Republicans were defeated in Spain and Africa. Sextus survived and was the last Republican standing, fighting the Second Triumvirate. Sextus had fought on land, particularly in Spain with his brother Gnaeus, as a capable Pompeian general. But he found a greater niche for himself as a very successful admiral of the seas, continuing to harass the great Augustus as a Sicilian pirate until defeated by Marcus Agrippa, captured, and executed.

5. Aaron Burr (1756-1836) — Aaron Burr served in the American Revolution, was a U.S. Senator from New York, and was the Vice President of the U.S. with Thomas Jefferson as President. In fact, he was defeated in his bid for the presidency in 1800 when Alexander Hamilton used his influence to thwart Burr and help Jefferson in the House of Representatives where the contested election was held. The feud between Hamilton and Burr eventually led Burr to mortally wound Hamilton in a dual at Weehawken in New Jersey in 1804. As Vice President, Burr presided over the famous impeachment proceedings against Supreme Court Justice Samuel P. Chase. Burr then went on a mysterious expedition in the southwest where he sought to either disconnect a western portion of the country from the United States or to conquer Mexico. Burr was absolved of treason charges brought against him for this adventure in another celebrated judicial trial. His only contender for this post is the famous duplicity of the American general James Wilkinson (1757-1825), who was also implicated in a conspiracy to split off the southwest as a separate territory from the United States.

4. King Harald Hardrada (“stern counsel”; 1015-1066) — Hardrada was King of Norway from 1046-1066. Hardrada invaded northern England at Northumberland in alliance with King Harold’s brother Tostig in 1066. Harold Godwinson, the English King, came up with his army and surprised King Hardrada and Tostig at Stamford Bridge, who in the vanguard had become dangerously detached from the rest of their army and fleet. Hardrada and Tostig were decisively defeated, killed in the battle, and their armies annihilated, forever ending Scandinavian invasions of the British isles. The word “berserk” of the Old Norse literature was used here in reference to the Norsemen’s furious attack that ensued this battle. Before his fatal invasion of England, Hardrada had roamed the European continent seeking adventure as a soldier of fortune, even serving in 1033-1034 with the Varangian guard of the Byzantine Empress Zoe and Emperor Michael IV. Hardrada was the last “Viking” and the last Norseman to terrify the North Seas. The remarkable story is told in the Saga of Harald Hardrada by the adventuresome author, Snorri Sturluson (c. 1230).

3. Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798) — Casanova was a Venetian adventurer, author, womanizer, traveler, and secret spy for his native Venice. He traveled all over Europe, gambling, writing his diary, and seducing women after escaping from the Venice prison, The Leads, in 1756. He became rich after becoming Director of the Lottery in Paris. He won and lost fortunes in his amorous adventures. Here is a man who made it to this list without spilling any blood or engaging in warfare, but by mostly following his adventures and amorous pursuits. Casanova died in Bohemia at the Castle of Dux while serving as a librarian and writing his memoirs. Those memoirs are probably one of the best ever written and certainly the most colorful and descriptive of life in Europe in the late 18th century.

2. Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-1682) — Rupert’s father, Frederick V, the Winter King, was deposed as protestant King of Bohemia (1619-1620). As a child, Rupert and his family wandered through Europe in exile. Prince Rupert possessed natural military ability and as a teenager fought with the Dutch army in the Thirty Years’ War. He was the nephew of Charles I and first cousin to Charles II, Kings of England. While still a young man, Rupert became Cavalry Commander (“Cavalier”) and the most audacious Royalist general in the English Civil War, fighting against the Parliamentary Puritan forces (“Roundheads”) to restore his uncle, Charles I, to the English throne. When his efforts failed, Rupert, like Sextus Pompey, resorted to piracy to sustain the Royalist cause. Despite Rupert’s perilous career — in which he lost his devoted, younger brother, Prince Maurice, and was himself wounded several times, requiring two dangerous trepanations for serious head wounds — he survived and lived through the Restoration to be appointed Constable of Windsor Castle. Prince Rupert was also an inventor of military ordnance, artillery and sea salvage gear. He served the Restoration Court as an administrator, commander of the army and admiral of the Royal Navy, while continuing to pursue various enterprises, founding the Royal Society with his cousin, King Charles II, and conducting scientific experiments. Rupert was also an artist, developing the mezzotint art of engraving. He helped plan explorations, draft maps, and settle Canada with his enterprising commercial venture, the Hudson Bay Company. In his later years, Rupert continued to serve in administrative posts, and died a natural death, being buried in Westminster Abbey with honors.

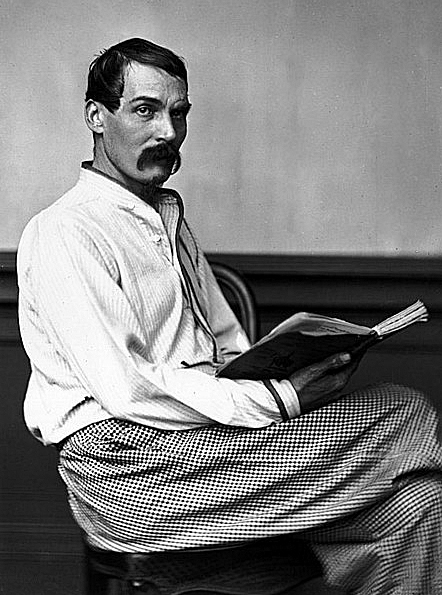

1. Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890) — Here is a man who, like Giacomo Casanova, was not involved in any defensive or offensive wars, but was largely an inquisitive and peaceful man of letters — and action. Burton was an explorer, linguist, ethnologist, and author. He was fluent in 29 languages, including Sanskrit, Hindustani, Arabic, and Persian; and disguised as an Arab, he traveled and visited the forbidden cities of Mecca and Medina in 1853. He translated the book, One Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights; 1885-1888) from Arabic to English and the Kama Sutra from Sanskrit to English. He also wrote scholarly, authoritative books on falconry and fencing, which are still the gold standard text in those areas. With John H. Speke, Burton explored the source of the Nile, through the jungles of central Africa and Lake Tanganyika. He served as a captain in the army of the East India Company. His wife was devoted to him and through her efforts, he was appointed British consul, serving in Santos, Brazil, and Damascus, Syria, as well as Trieste, where he continued his explorations of the areas under his jurisdiction. Burton was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and was awarded knighthood in 1886 by Queen Victoria.

That was my list; who’s in yours?

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.), Mercer University School of Medicine. Dr. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). Dr Faria has written numerous articles on Stalin, communism, and the Soviet Union, all posted at the author’s website: https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. The Ten Greatest Adventurers in History. HaciendaPublishing.com, April 1, 2014. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-ten-greatest-adventurers-in-history.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

2 thoughts on “The Ten Greatest Adventurers in History”

Re. Pope Alexander VI: The Treaty of Tordesillas: June 7, 1494. By Jesús Vico and Beatriz Camino.

On this day in 1494, the kingdoms of Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, an agreement that divided the territories of the “New World” into two spheres of influence. The consequences of this agreement can still be appreciated nowadays throughout America. The Treaty of Tordesillas was aimed to solve any kind of dispute that might arise between Portugal and Spain regarding the newly discovered territories in the New World. Before the discovery of America, both kingdoms had signed the Treaty of Alcácovas (1479), which granted all lands south of the Canary Islands to Portugal. However, when Christopher Columbus, who had sailed under the sponsorship of the Castilian crown, proved to Portuguese King John II that there were more islands to the southwest of the Canary Islands he became infuriated. He claimed that these territories belonged to Portugal and threatened the Catholic Kings with invading them. The latter, whose military power in the Atlantic could not match the Portuguese, sought a diplomatic solution.

Isabella and Ferdinand decided to ask for help from Pope Alexander VI, who issued a papal bull in 1493. In this document, he claimed that the world should be divided by an imaginary meridian crossing between the north and south pole. According to it, all of the territories to the west of this line belonged to Spain and those to the east to Portugal. He also added an important clause which stated that if a new Christian kingdom was discovered, it could not be conquered. The Treaty was signed on 7 June 1494 in the Spanish town of Tordesillas. Pope Alexander’s decision was maintained, but the line was shifted to 370 leagues west of Cape Verde. The document established two spheres of influence but did not consider geographical matters such as coastlines.

On one hand, the Portuguese were given free rein west and south of Melilla in Morocco and gained the eastern part of current Brazil. On the other, Spain gained most of the lands of the Americas and focused on the stretch of the North African coast opposite the Canary Islands. Still, the line was not strictly enforced, as the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the line. Moreover, the treaty permitted either country’s ships to sail across the water under the other’s jurisdiction in order to access lands that were under their control.

After the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed, both empires quickly set out their sights to discover more territories and the colonial competition started. However, there was a missing piece in the treaty: the meridian only divided one part of the world. This proved to be a problem when explorer Ferdinand Magellan, sailing under the service of Spain, reached East Asia by crossing the Pacific Ocean in 1519-1522. There, Spain established control over the Maluku Islands, which were the source of many spices and a very important trading post. As a result, the Portuguese quickly argued that they also had a claim on the islands. Since there existed no meridian that divided this part of the world, negotiations took place over several years to determine on which side of the sphere the islands were located. Finally, they reached an agreement in 1529 with the Treaty of Zaragoza, which established an anti-meridian and gave Portugal control of the East Indies and Spain the Pacific Islands and the Americas.

Nevertheless, Spain and Portugal’s spheres of influence quickly changed as the British, French and Dutch began to wonder whether they could also benefit from the riches of the Americas. With the arrival of the Reformation in the 16th century, nations challenged papal authority and sought their own overseas territories. Thus, they ignored the Treaty of Tordesillas, which had been decreed by the Pope, and set out to achieve this goal.

Still, the Treaty of Tordesillas remains the first official document that divided the world for colonization and its consequences can still be appreciated today. For example, Spanish is the dominant language in Latin and South America with the exception of Brazil which, as established in the agreement, was under the control of Portugal.

I should have been able to squeeze Pierre Agustin Caron de Beaumarchais, author of the Marriage of Figaro, in this list. The theater was a center of politics in France in the 1780s. By the time Figaro was shown in theaters, Beaumarchais was not the oppressed character in the drama but “an ennobled magistrate of considerable wealth and influence.”[1] He was not just another chic aristocrat denouncing the established order and sneering at the ancient regime that nurtured him, but a man of many faces and talents. He had been “magistrate and prisoner, courtier, and rebel, diplomat and spy, businessman and bankrupt publisher and publicist, insider and outsider.” Besides he was also the playwright who became famous with the Barber of Seville. But the reason he should be mentioned is that he was a great friend of the American Revolution, “who fitted out an entire private navy and armaments for the rebels and whose own pocket made up the difference between the escalating cost of French assistance and secret royal disbursements.”[2] Another project brought Beaumarchais ruin, and that was the publication of the complete works of Voltaire, a formidable project that other publishers refused to undertake and that was opposed by Frederick the Great of Prussia, who did not want his correspondence with Voltaire mad public. This whole project was sabotaged, disrupted, “the entire business was a commercial fiasco of titanic proportions. But it was also a cultural glory, perhaps the fines thing Beaumarchais ever did.”[2]

And yet, The Marriage of Figaro did considerable damage to the ancient regime. If the intelligentsia and aristocracy did not actively began the French revolution, they contributed greatly to undermine it. With his plays, even Beaumarchais, contributed to the demolition of the old regime. As I alluded to, he was an enterprising adventurer and a great man of many talents and ambiguities of character. “While there had been plenty of boulevard comedies assailing the pretensions of seigneurial power, none had done so with such stinging hilarity.” This dangerous play undermining the aristocracy was a “people’s drama” that even Queen Marie Antoinette wanted to see and saw in a private setting. Even Beaumarchais who was present “rose from his chair and, in a rare fit of eloquence and prescience, declared that it was ‘detestable. It will never be played; the Bastille would have to be destroyed if the performance of the play is not to have dangerous consequences.’ “[3] Double entendres and popular songs sneering at the British humiliation in America were later incorporated into the play. “As usual. though, it was the eagerness of a section of the fashionable nobility to humiliate the court that undermined the latter’s authority.”[3] But Beaumarchais did not neglect to humiliate the aristocracy, the same nobility that he had bought into in 1761 and that he had relatively lately joined, entitled then to use the name of his estate—Beaumarchais.[1]. When The Marriage of Figaro was opened to the public in 1784, the aristocrats were astonished when they were slapped in the face when Figaro turns his fury on a count in his play:

“Because you are grand seigneur you think yourself a great genius… nobility, wealth, rank, offices! all this makes you so high and mighty! What have you done to have so much? you’ve hardly given yourself the trouble to be born and what that’s about it: for the rest you’re an ordinary person while I damn it, lost in the anonymous crowd, have had to use all mu science and craft just to survive.” A member of the audience observed that some of the nobles there, “smacked themselves across their own cheeks; they laughed at their own expense and what is even worse they made others laugh to… strange blindness.”[4]

The Revolution came. The same day as the fall of the monarchy, August 10, 1792, Beaumarchais’ grand house at faubourg Saint-Antoine was ransacked by the Paris Commune, who had accused him of hiding large cache of arms for suspicious reasons. Ironically, he had purchased and trafficked on arms for the American Revolution, and now he was accused of doing so against the French revolutionary government. This was also a time to settle scores since he was hated by Jean Paul Marat. He was arrested on August 23 and was confined by orders of Marat. He was fortunate to have been released four days before the September massacres began.[5]

Notes

1. Schama, Citizen, pages 138-139.

2. Schama, Citizen, page, 141.

3. Schama, Citizen, page, 142.

4. Schama, Citizen, page, 143-144.

5. Schama, Citizen, page, 625-626