- Articles, Religion and History

Religion as the Opiate of the People? by Miguel A. Faria, MD

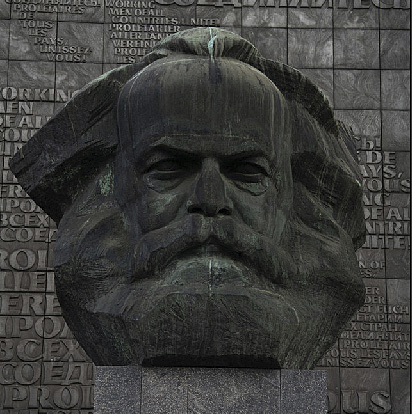

Recently, as if on cue, I have noticed liberal jabs at religion of a peculiar nature. It is as if, from the coldness of his tomb, Karl Marx (photo, below) was inciting these little jabs by his latter day disciples to prop up yet another aspect of his failing communist (socialist) philosophy, a philosophy that refuses to die. In his Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx wrote, “Religion is the opiate of the people.” Lenin expounded, “Religion is one of the forms of spiritual oppression that everywhere weighs on the masses of the people, who are crushed by perpetual toil…Religion is the opium of the people. Religion is a kind of spiritual gin in which the slaves of capital drown their human shape and their claims to any decent human life.”

In my local newspaper, The Telegraph (Macon, Georgia), a Viewpoints poster opined that the “revealed religions,” particularly the Christian church, were created to control the people. Another Viewpoints poster then replied, “Religion is by far the worse thing to ever happen to humanity. Religion is the reason for all the wars…”

It would seem that to answer such assertions would take a historic thesis, not to mention a full-length book, so such provocative statements often go unchallenged. Residing in the hollow, ivory towers of modern-day academia, shallow professors — now teaching at a 7th grade reading level but with still considerable hubris — instruct students with such clichés and without much substance. Furthermore, one gets the impression that making those assertions gives the speaker “an intellectual” aura above the idolatrous masses. Perhaps, a few historic points of fact on the Christian religion and its relationship to the state — and a little logic can help us elucidate and make some historic sense.

From the 1st century AD, when the first Christian churches were established, until AD 312, Christians practiced their religion underground. Christians were persecuted and martyrs were created in the gladiatorial Roman arenas or wherever the unrepentant faithful were found. Instead of extermination of the Christians, from the reigns of Nero (AD 34-68) to Diocletian (AD 284-305), the persecutions helped to fortify the religion. The Romans, who admired stoicism, secretly came to admire the uncompromising Christians, who died rather than renounce their faith, and the Christian church continued to grow underground. In AD 312, Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, and established the Christian faith as a legal Roman state religion. Suddenly, a previously persecuted religion had become supreme, one of the greatest turning points in history!

During the 4th and 5th centuries in Rome and in Constantinople, the church and the state supported each other. The moral code and the laws were supported by the state and church cooperation. Nevertheless dissension among the Christians created significant disturbances within the empire, and the emperors must have questioned the wisdom and benefits of a state-sponsored religion, yet they persevered in their support of orthodox Christianity.

In 476, Rome fell and the Empire of the West collapsed. Germanic barbarians entered the gates. Romans and other Christians were protected by these Germanic barbarians, who were for the most part Arian Christians. Saint Augustine’s The City of God is instructive in understanding these trying years before the final collapse of the Roman Empire of the West.

From the 5th century to the 10th century, during the Dark Ages in the West, a citizen of the fallen Roman Empire fortunate enough to reach the safety of a Christian monastery could receive sanctuary and food and shelter as well as physical and spiritual protection. Nowhere could one be safer than in the Christian monasteries during the Dark Ages and the early Medieval period, and find peace of body and soul from the barbarism and turbulence of the time.

From roughly the 11th to the 14th century in the Medieval period, the Christian church built hospitals and universities, and its teachings weakened and finally ended slavery in the West; feudalism, though, reigned, and cooperation between church and state was tenuous at best. Holy Roman Emperors and the Popes carried out a life and death struggle, in which, despite the charisma of Pope Innocent III (1160-1216), the labors of Gregory VII (1073-1085), and the penance of Henry IV going to Canossa in 1077, ended with a victory for the emperors over the popes in particular and the state over the church in general.

From the 14th century to the 18th century came the Renaissance and humanism, not to mention the Protestant Reformation; the Century of Genius (17th century) brought religious wars, but also voyages of discovery, commercialism, and the creation of wealth led by Portugal, Spain, and then the Dutch Republic with more religious freedom, except in Spain and Austria; the rediscovery of the Classics of Greece and Rome; then the Age of Reason, rationalism, and the Enlightenment followed. Philip II (1556-1598) ruled with the consent of the church and enforced religious conformity in Spain, just as Louis XIV (1643-1715) did in France, for a time. But John Locke, Baron Montesquieu, Voltaire and the Philosophes had their say and soon the Divine Rights of Kings came tumbling down and the influence of religion further waned in government and in the populace.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) convulsed the world bringing untold suffering, violence, and death. The Church had reached a nadir in respect and power. In 1804, Napoleon took the crown from Pope Pius VII and put it on his own head and then crowned Josephine, his wife.

For centuries, the Christian religion and Judeo-Christian ethics had provided solace and comfort to the poor and downtrodden from the hardships, vicissitudes, as well as the barbarities of life during the Dark Ages and later feudalism. These pillars also provided support to the moral code, and yes, the church also frequently bolstered the laws of the realm. At the height of the Middle Ages, the clash between the Church and the State reached a crescendo with the conflict for supremacy between Pope and Holy Roman Emperor. The support of the populace swayed between the two, but as we have seen, the empire triumphed over the church.

In the 19th century, Britain ruled the seas and much of the world. The sun never set in this empire, as it never set previously in that of Charles V, Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor. The church had considerable influence during the reign of Charles V, but not enough to prevent the sack of Rome or the humiliation of the Pope Clement VII (1523-34). There was even less ecclesiastical influence in the secular empire of the Empress of India, Queen Victoria (below), and her Prime Ministers Gladstone and Disraeli had little inclination to force religion on the people. The British people supported the Anglican Church enough to sustain the moral code, while engaging in freedom and trade, with little intrusion in the lives of Englishmen.

Critics may say that I am generalizing and giving short shrift to certain historic events. But, how can anyone not do so in such a short essay? My intention is just to give a response in the popular press to blanket statements, such as “the Church was created to control people.” If the critic really means that the church and Judeo-Christian ethics have supported the moral code, then there is, after all, no disagreement. We only disagree if the critic contends that the moral code need not be supported by religion. He can have his say and prove his point with his own thesis.

Did the church support oppression of the people? Sometimes, it did. And yes, the church did not support insurrections against rulers that had very little chance of success. Likewise, the church opposed unjust wars and the needless spilling of blood in wars or insurrections. What the Christian religion supported more frequently was peace and civility. And even more frequently, the church made life more tolerable for the belabored citizen, who for most of written history has led a precarious existence, bordering on subsistence, penury, famine, suffering, disease, violence and premature death.

The church brought holidays, festivals, charity, saint days (feast days), and sometimes sustenance, bodily and spiritually, as well as justice and peace. Most people in the West will agree with me that a theocracy is not the ideal government. One only has to remember the iniquities of Geneva under John Calvin or Cromwell’s Parliament of Puritan Saints after the English Civil War. But it is ironic that the opposite state of affairs has not been discussed with equal unanimity. Because when the state rules absolutely and without benefit of clergy, the most malevolent tyrannies and barbarities become the rule. Witness the Soviet Union, 1917-1991; Nazi Germany, 1934-1945; China, 1949-to the present day; and various other collectivist, atheistic regimes. The Christian church had no dominion in most of these regimes. And what are the statistics? One hundred million people butchered by their own government in the preceding 20th century!

With totalitarianism and collectivism, whether in the form of Nazism or most commonly, socialism or communism, there was neither constraint upon the state by any religious scruples nor a secured moral code “propped up” by religion to protect the people. And in these totalitarian states, there was no control of the people by the church. Religious guidance of the moral code was not necessary in a police state swarming with informants, national identification cards, intensive surveillance, and non-functioning, persecuted churches — the Total State controlled it all!

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is a former Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery and Adjunct Professor of Medical History. Dr. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). He has written numerous articles on the blessings of liberty and the venalities of totalitarianism, collectivism, and communism — all posted at his website: HaciendaPublishing.com.

The article can be cited as: Faria MA. Religion as the opiate of the people? HaciendaPublishing.com, September 7, 2011. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/religion-as-the-opiate-of-the-people-by-miguel-a-faria-md/.

Copyright © 2011 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Religion as the Opiate of the People? by Miguel A. Faria, MD”

Is it religion or would wars be fought regardless? Human nature would inevitably start conflicts . Territory, hunting lands, women, possessions etc. A Government of religion ( Theocracy) is most dangerous ! My opinion.— DM

Man is a bellicose creature with a all the savagery and inherent fallibility of human nature, and he would start wars for, as you said, for “territory, hunting lands, women, possessions”; and even more, such as failed diplomacy, wrong politics (“national honor”), as well as more crude reasons, such as capturing prisoners solely for sacrifice (Aztecs), for slavery, to trade, and yes religion. Bad men would join police forces, especially in police states, to satisfy their psychopathic tendencies, just as some bad men (if only a few fortunately) would join the church to cover their perversions and evil tendencies, especially during the inquisition(which has been greatly exaggerated— “the Black Legend”) Theocracy is bad, but the State, worshiped as a civil religion, as in communist and fascist countries is much worse— history teaches this and the 20th century is a great instructor.