- Articles

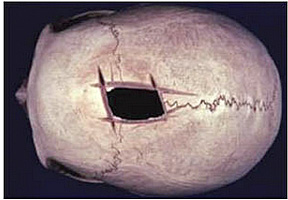

Primitive cranial surgery — Scythian trepanations (500-300 B.C.)

Letter to the Editor

World Neurosurgery

Dear Editor,

I found the article by Dr. James T. Goodrich on early Scythian trepanations succinct and interesting.[3] There are, nevertheless, a couple of points that need clarification and further explanation. Additionally, Goodrich asks an intriguing question that at least in my estimation has been adequately answered.

First, it must be stated that the trepanations that were performed by primitive surgeons usually took place in the Neolithic Age (New Stone Age) of the various civilizations, not in the Bronze or Iron Ages. And these ages refer to the state of development of those cultures and the predominant tools used in daily life: Polished stone for the Neolithic Age; bronze, for Bronze Age; and iron, for Iron Age. The time period for the Neolithic Age varied widely beginning from 10,000 years ago for the Middle East; 6000 B.C. for Egypt and North Africa; to 4500 B.C. for Europe, respectively. The Neolithic Age ended in most cultures of Europe, Asia, and North Africa by 2000 B.C. In Mesoamerica, the equivalent time period of development is from 4500 B.C. extending virtually up to the time of the Spanish conquest in A.D.1500.

Second, the region under discussion, as noted by the author, the Altay area of Russia (ancient Scythia) was inhabited in the period 500-300 B.C. by mounted nomads and fierce warriors. I agree with Goodrich that while Hippocrates lived in c. 460 – c. 370 B.C., practicing mostly in the island of Cos, there was little surgical knowledge transmitted from his school of Cos to the untamed Scythians during this time. Any connection is tenuous at best. Hippocratic physicians did practice trepanation, and the indications, in fact, were excessively wide as to promote unnecessary surgery in most instances of head injuries. But the dura was not penetrated.[5] Other than the time period, there is no cultural connection between the primitive trepanation of the Scythians using copper or bronze tools and those of the Greek physicians using more precise iron medical instruments.

Goodrich’s three cases are interesting and intriguing because they were performed by primitive surgeons in a much later period, when the Bronze Age was ending and the Iron Age beginning for that part of the world. Goodrich writes, “Moving out of the Iron Age and into the Bronze Age…”[3] Here I must correct the author: The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age and not the other way around. It is also of interest that copper shavings were found at the trepanation sites, which may have reduced the risk of infection in those cases.[3]

Finally, Goodrich asks the question that has captivated scholars since the time of the French physician and anthropologist Paul Brocas (1824-1880) as well as scholars for nearly two centuries.[6] In Goodrich’s three cases there was no evidence of trauma. He writes, “An unanswered question still remains: Why do a trepanation?” I had asked myself the same question, and my conjecture was similar to Goodrich; trepanations must have been for “tumors, headaches, seizures, demons, or some other medical illnesses.” I suspected mental illnesses as well. Since the publication of that article,[2] I have conducted an investigation into the matter and rediscovered the work of the late medical historian Plinio Prioreschi, MD, PhD (1930-2014). In fact the mystery of why primitive surgeons performed cranial surgery had been solved by Dr. Prioreschi, but his findings had gone unrecognized. Ancient trepanations were performed to bring comatose or obtunded warriors or members of their families back to life. I invite you to read further on this fascinating discovery.[1,4]

References

1. Faria MA. Neolithic trepanation decoded — A unifying hypothesis: Has the mystery as to why primitive surgeons performed cranial surgery been solved? Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:72. Available from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2015/6/1/72/156634

2. Faria MA. Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 1 — From trephination to lobotomy. Surg Neurol Int 2013;4:49. Available from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2013/4/1/49/110146

3. Goodrich JT. Early Surgeons Performing Trepanation: An Examination of Scythian Trepanations in the Gorny Altai at Hippocratic Times. World Neurosurg (2015)83.3:305-307. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2014.10.009

4. Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine, Vol. I: Primitive and Ancient Medicine. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995, p. 21-32.

5. Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine, Vol. II: Greek Medicine. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1996, p. 335-346; 376.

6. Walker AE, editor. A History of Neurological Surgery. New York, NY: Hafner Publishing; 1967, p. 1-22.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, M.D., is Associate Editor in Chief in neuropsychiatry; history of medicine; and socioeconomics, politics, and world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI). He was appointed and served at the behest of President George W. Bush as member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2002-2005. Dr. Faria is a Board Certified Neurological Surgeon (American Association of Neurological Surgeons; retired); Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is the author of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His recently released book is America, Guns, and Freedom: A Journey Into Politics and the Public Health & Gun Control Movements (2019).

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Primitive cranial surgery — Scythian trepanations (500-300 B.C.). World Neurosurg. 2015 Oct;84(4):1174. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/primitive-cranial-surgery–scythian-trepanations-500-300-b-c/.

Copyright ©2015 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.