- Articles

On Revolutionary Physicians and Civil Wars by Miguel A. Faria, MD

A man without ethics is a wild beast loosed upon this world.

Albert Camus (1913-1960)

French Existentialist

Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom must, like men, undergo the fatigue of supporting it.

Thomas Paine (1737-1809)

Anglo-American patriot

Throughout the ages, some physicians have had more than a passing interest in politics, justice, and the mechanics of government. For example, the illustrious American physician, Benjamin Rush (1745-1813), one of the fathers of American psychiatry and a highly esteemed physician in his own day, was also one of the 56 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. Rush was one of four physicians to proclaim: “with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honour.”* And, by signing their names on that political document par excellence, these men took a courageous and bold stand against the course of tyranny. Benjamin Rush did not end his political career with the signing of the document, for in addition to being an indefatigable physician and a prolific writer, he was also a founder of the first American antislavery society, and served as a treasurer of the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia.(1)

In this month’s editorial, I have chosen to write about medical facets in the events surrounding two civil wars, the English Civil War of the mid-17th century and the American Civil War of the 19th century (the latter also know as the War Between the States and the War of Northern Aggression by the Confederacy and the French Revolution, and relate, for better or for worse, the part played by certain physicians in those pivotal moments.

The English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642-1648) had epochal ramifications relevant to the European concept of the divine rights of kings, and the role of a constitutional (limited) monarchy relative to representative government in the Western world.

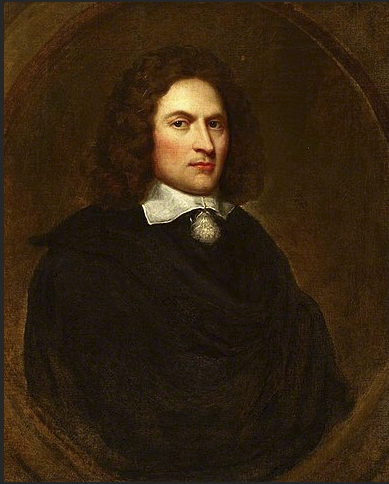

Two men intimately involved in the English Civil War were the physicians Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689), “the English Hippocrates,” and Richard Wiseman (1625-1686), the greatest English surgeon of his day. What is more, these practitioners fought in opposing camps. Sydenham was a cavalry officer for the Puritan Parliamentary forces, the “Roundheads,” whereas Wiseman was a “cavalier,” an ardent Royalist. Moreover, Wiseman became a personal friend of King Charles II, just as the preeminent physician William Harvey (1578-1657) had been a good friend (and hunting partner) of King Charles I.

In the intense conflict of the English Civil War, the issue of whether the royal prerogative (for English monarchs to govern) deriving its authority from the divine right of kings, or whether Parliament deriving its powers from English Common Law and fortified by the Magna Carta (1215), had the right to supersede or at least limit the royal prerogative by Parliament’s control of the nation’s purse.**

The conflict had begun during the reign of James I but the situation had deteriorated into civil war amidst the reign of his son, the obdurate Charles I (King, 1625-1649) who had not only refused to allow Parliament to curtail his power but had also levied forced taxes upon the populace without Parliament’s consent. He had gone even further by dissolving Parliament and ruling without it for 11 years. Needing money for his war in Scotland, Charles finally recalled Parliament. The Long Parliament (1640) responded by announcing the Grand Remonstrance, a recitation of the alleged iniquities of Charles’ reign. War became inevitable.

The Royal Cavaliers engaged the Roundheads on the field of battle, and after several indecisive engagements, the Parliamentary forces, reorganized and led by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), turned the tide of war. The Puritans then defeated the Royalists at both the battles of Marston Moor (1644) and Naseby (1645). The King was finally captured in 1646 and tried by his mortal enemies who controlled the high tribunal. This was a sort of kangaroo court, for via (Thomas) Pride’s Purge, all of those opposed to the Army’s Council — which was headed by Cromwell and already committed to regicide — were expelled from Parliament. The Parliament that was left to judge the King became the Rump Parliament, and the fate of the King was thereby sealed. He was beheaded on January 27, 1649. The Prince of Wales, the future Charles II (King, 1660-1685), made two courageous but unsuccessful attempts to save his father from the executioner’s ax.

At age 19, young Sydenham interrupted his education at Oxford to take up arms on the side of the Parliamentary forces, joining his father and older brothers, all of whom were cavalry officers. He fought the Cavaliers in a cavalry regiment near Dorset until he was wounded in the battle of Weymouth (1645); in this battle, he also lost his eldest brother Francis. Once he had recuperated and the Royalists had been driven out of Dorset, he ventured to complete his medical studies at Oxford.(2)

The medical historian Elmer Bendiner, writing about Sydenham’s recuperation, relates: “Medical historians are fond of picturing the scene in which the recuperating Thomas Sydenham, unaware that he would one day be England’s most celebrated physician, gazed across a narrow stream at the Royalist camp where Richard Wiseman, up to his elbows in the battered bodies of the king’s soldiers, was rehearsing his own future as England’s most prominent surgeon.”(2) Thomas went on to become good friends of the scholars John Locke and Robert Boyle and would one day be recognized as the greatest clinician of his age.

Richard Wiseman was one of the greatest surgeons of the “Century of Genius.” His medical-military career began when, at the age of 15, he became a surgical apprentice, and shortly thereafter, a naval surgeon in the Dutch navy — the Netherlands being a long-standing ally of England. Amidst the upheaval of the civil war, he returned to England and joined the Cavaliers as military surgeon. At the battle of Weymouth in 1645, he found himself on the verge of being captured by the Roundheads. In fact, he came close to being apprehended by Colonel William Sydenham (one of Thomas’ older brothers). Fortunately, he had befriended the Prince of Wales, the commander of the Royalist forces, and after the decisive defeat of the Cavaliers in that battle, they — prince and surgeon — escaped to France. Wiseman also accompanied the Prince to Holland and then to Scotland; where the Prince raised another army that invaded Northern England in a last ditch attempt to save his father. At the battle of Worcester in 1651, Wiseman excelled by bravely exposing himself to treat the wounded, including “several soldiers with severe head injuries.”(3) Finally, after Worcester, the intrepid surgeon was captured and imprisoned.

At Old Bailey, the English prison, he was allowed to practice surgery and actually prospered until 1654 when he was implicated in a Royalist plot. But as the maxim proclaims, fortune favors the brave — the evidence was insufficient, and he was again given enough liberty to see his patients. Nevertheless, life had become very difficult for a suspected Royalist, and he was forced once again to flee England.

Dr. Wiseman joined the Spanish Navy where he served for 3 years, until, anticipating the restoration of 1660, he returned to London. A medical historian writes, “Charles II returned to London on May 29, 1660. For his loyal service, Wiseman was appointed Surgeon in Ordinary to the Person.”(4) He reached a pinnacle of glory in 1672 when he ascended to the rank of “sergeant-surgeon and principal surgeon to the King.”(5)

The French Revolution

The French Revolution (and her motto, liberté, egalité, fraternité) had profound repercussions throughout the 19th century. France’s egalitarian philosophy did not reach full fruition, however, until the Red October Revolution of 1917, which gave birth to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and its veritable “evil empire” that resulted directly or indirectly in the deaths of 100 million people worldwide. The French Revolution did, in fact, provide a socialist paradigm for the totalitarian Marxist states to follow in our turbulent 20th century.

Perhaps the most recognizable name to spring out of the annals of the French Revolution is Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the professor of anatomy who devised the macrotome that bears his name. To the guillotine, 20,000 men, women and children lost their heads during the Reign of Terror between June of 1793 and July 1794. Dr. Guillotin served on various medical and public health committees during the French Revolution. It was on one of these committees that he proposed the use of the guillotine as a humane way for the “Republic of Virtue” to rid itself of the aristocrats and other enemies of the Revolution.

Jean Paul Marat (1743-1793) was another famous physician of the French Revolution. As a member of the radical wing of the Jacobin party (the Leftist Mountain), he forcefully opposed the more moderate Girondins at the French National Convention.*** The struggle between the two factions came to a head, but Marat prevailed and sent many of his foes to the guillotine in June 1793 — an event that triggered the Reign of Terror. In retaliation, Charlotte Corday, the daughter of one of the executed Girondin leaders, stabbed the radical physician to death while in his bathtub on July 13, 1793. The young woman followed her father to the guillotine for her act of revenge.

Interestingly, Marat required long warm baths because of a severe skin condition which had been aggravated by his hiding and living in the underground Paris sewers as an outlawed revolutionary in the years before July of 1789 and the Fall of the Bastille. The fact that he was known to take long baths to ameliorate his skin condition facilitated his assassination.

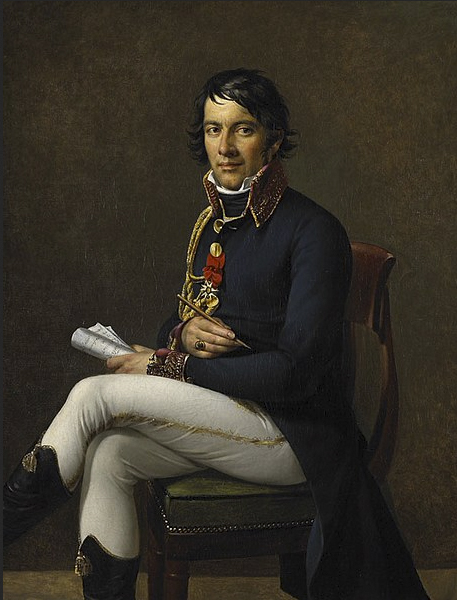

Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766-1842), the hero of countless Napoleonic campaigns, has remained overshadowed by the political notoriety of other participants in the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Yet he was highly respected by friends and foes alike during his time. As Napoleon’s military surgeon, he reorganized the medical corps in the battlefield and developed the celebrated ambulance volante, the “flying ambulances,” to expedite transportation of the wounded and facilitate medical treatment of wounded soldiers. Even in the harsh arid desert terrain of Egypt, his flying ambulances would collect the wounded in less than 15 minutes.

Dr. Larrey has been touted as having personally performed 200 amputations within a 24-hour period amid and after the Battle of Borodino during Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. He followed Napoleon in every campaign from the Egyptian campaign of 1799, through Austerlitz, 1805; Moscow, 1812; and even accompanied the Emperor after his escape from the Mediterranean island of Elba, through the famous “100 days,” and finally to Waterloo on the fateful day of June 18, 1815. Larrey was adored by the public and admired by his colleagues, while living in one of the most turbulent periods in history.(6)

The American Civil War

The U.S. Civil War’s immediate impact was felt mostly in America. The bloody fratricidal conflict ended slavery, preserved the union, and reaffirmed the natural rights of man first proclaimed distinctly by the English physician-philosopher, John Locke (1632-1704), the foremost proponent of individual rights. Locke had written that all human beings were equal and free to pursue “life, health, liberty, and possessions.”(1) He influenced our American Founding Fathers immensely. In the words of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826):

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them…. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the consent of the governed.

Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

The shot fired at Fort Sumter at 4:30 AM on April 12, 1861, meant that the time of reckoning had finally arrived, and the account owed to the inherent natural rights of man that the Founding Fathers knew would have to be settled, sooner or later, was to be finally paid in full with the precious blood of American brethren, Northerners and Southerners.

Although General George B. McClellan (1826-1885), “the Little Napoleon,” has received little credit for his accomplishments during the American Civil War, the fact is that he reorganized and built the Army of the Potomac into a massive and mighty fighting force. He also allowed the tremendous reorganization of the military corps, in the tradition of Baron Larrey, under the leadership of 1st Lieutenant William A. Hammond (1828-1900). Hammond was appointed Surgeon-General on April 25, 1862, and his invaluable associate, Jonathan Letterman, MD, was appointed Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac on July 4, 1862. The two men, supported by General McClellan, developed “the first ambulance unit, field supply systems, full hospitals and corps inspectors.”(7) The difference was dramatic.

After the First Battle of Bull Run (July 18, 1861), the wounded were left on the bloody battlefield for days without medical attention. This was not to be the case after the battles of Antietam, Sharpsburg, and Fredericksburg, bloody as these battles were for both sides, especially the Union forces.

Medical historian Harry Bloch, MD, maintains that Hammond’s reforms were invaluable and were only impeded by the jealousy and rivalry of the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, who “deliberately suppressed [Hammond’s] projects.” Hammond was unjustly dismissed (August 1863) and Letterman resigned (November 1864), leaving, nevertheless, a reorganized medical corps. A Congressional Military Affairs Committee exonerated Hammond in 1878, and Rutherford B. Hayes (U.S. President, 1877-1881) restored him to the rank of Brigadier General, retired.

Hammond’s legacy is a cornucopia of contributions: the monumental Medical and Surgical History of the War; improved medical military standards; impetus for the completion of the military library, medical museum, and Army Medical School — not to mention his work in neurology. Letterman left his own individual and notable contributions to military medicine.(7)

As Dr. Waldo E. Floyd, Jr.’s, feature article elsewhere in this issue, Southern Medicine During the War Between the States, and the experiences of Drs. Samuel Preston Moore and John Julian Chism therein described will demonstrate, physicians then were not only political at heart but always performed their duty in the service of their country.

Footnotes

* The other physicians were Josiah Bartlett (1729-1795) who was also a judge from New Hampshire; Matthew Thornton (1714-1803) also of New Hampshire; and Lyman Hall (1724-1790) of Georgia.

** There was also a side but complex issue of the episcopacy opposed by the Scottish Presbyterians who resented and went to war with the king over the episcopate and the imposition of the book of common prayer in Scotland.(1)

*** It has been the seating arrangement in the French National Convention with the Mountains on the left and the Girondins on the right that the political term, Right and Left (wings) came into existence — and persist to this day.

References

1. Columbia Encyclopedia. Franklin Electronic Publisher, Inc., Mt. Holley, NY 08060. Columbia Univ Press, 1989.

2. Bendiner E. Thomas Sydenham — The English Hippocrates. Hosp Pract 1986; July 15:183-213.

3. Bakay L. Richard Wiseman. A Royalist surgeon of the English Civil War. Surg Neurol 1987;27:415-418.

4. Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. New York, Bell Publishing Company, 1988.

5. Smith AD. Richard Wiseman — His contributions to English surgery. Bull NY Acad Med 1970;46(3):167-182.

6. Faria MA. Dominique-Jean Larrey: Napoleon’s surgeon from Egypt to Waterloo. J Med Assoc Ga, 1990;September:693-695. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/dominique-jean-larrey-napoleons-surgeon-from-egypt-to-waterloo.

7. Faria MA. Medical politics during the Civil War. HaciendaPublishing.com, February 20, 2016. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/medical-politics-during-the-civil-war.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief in neuropsychiatry; socioeconomics, politics, medicine, and world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI). Author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His latest book is America, Guns, and Freedom: A Journey Into Politics and the Public Health & Gun Control Movements (2019).

This article was originally published in the Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia, Volume 83, Number 2, February 1994, but was revised and updated on June 3, 2022.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. On Revolutionary Physicians and Civil Wars. HaciendaPublishing.com, June 3, 2022. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/on-revolutionary-physicians-and-civil-wars-by-miguel-a-faria-md.

Copyright 1994-2022 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD