- Articles

Interview With Dr. Miguel Faria (Part I) by Myles B. Kantor

Miguel A. Faria Jr. is the author of Medical Warrior and Vandals at the Gates of Medicine, and former editor in chief of the Medical Sentinel. He is presently Associate editor-in-chief and a World Affairs editor of Surgical neurology International (SNI) His most recent book is Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise. A retired neurosurgeon, Dr. Faria lives in Macon, Ga.

In this interview reporter Myles Kantor interviews Dr. Miguel Faria about the daring but suicidal attack on the Presidential Palace of Fulgencio Batista in Havana on March 13, 1957, carried out by the Student Revolutionary Directorate, an anti-communist organization in which his parents played a role in the urban underground fighting Batista.

The questions by Mr. Kantor are in bold, the answers by Dr. Faria in plain text.

An aspect that struck me about Cuba in Revolution is its combination of autobiography and meticulous analysis. When did you decide to write this book?

Myles, the subject of Cuban tyranny and the suffering of the Cuban people, including my relatives who remain imprisoned in the island gulag, have been in the back of my mind from the time of my arrival in Miami at age 13 in 1966, from my graduation from medical school through my post-graduate training in neurological surgery at Emory University in the late 1970s, to my professional life in the 1980s and 1990s.

You can say that I have been researching and pondering the troubling subject for decades. Whenever I could, I questioned my parents (who sometimes wanted to forget) and I read articles about Cuba that sporadically fell into my hands. Practicing neurosurgery, writing and editing medical articles and journals took a lot of time.

But then, a miraculous event took place on Thanksgiving Day 1999 a 6-year-old Cuban boy, floating on an inner tube, was rescued from the treacherous waters of the Atlantic Ocean. It was said that dolphins protected Elián González from the roaming sharks. That event, which later became a cause célèbre, changed my life.

Years of subconscious research, smoldering passions, hidden emotions, troubling dreams all came to a head. I identified with the hapless boy and his uncertain future. I wanted him to have the same opportunities in freedom that I had. I began to write letters to newspapers, calling and speaking on radio shows, and even participated in one of the demonstrations in Miami in front of Elián’s home.

My first article on the subject was published that spring in NewsMax.com and it was a hit. I began to write frantically, often awaking at 3:00 a.m. to write for long stretches about my experiences and recollections about Cuba. The result was that the first draft of my book was written in 11 days. It was the story of my family’s involvement in the Cuban Revolution, our subsequent disillusionment with the communist betrayal, and finally my own escape (with my father) on the high seas to reach for freedom.

That Elían was inimically sent back to the living hell of Cuban communism (fascism) only redoubled my efforts to combat tyranny. Old-fashioned ink and paper were my weapons, and I began to add chapters to the book, bringing up to date the history of Cuban infamy. These efforts did not end with publication of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise. They will continue.

You devote a considerable amount of the book to “the other Cuban revolutionaries” of the Revolutionary Directorate. What was the Revolutionary Directorate?

The exploits of the Student Revolutionary Directorate (RD; Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil), the other group of Cuban revolutionaries who fought against dictator Fulgencio Batista and to which my parents belonged, is an untold chapter of the Cuban Revolution. This chronicle is important, for had this group prevailed, the course of Cuban history would have been very different.

Unfortunately, the Cuban press (even under Batista!), and most importantly the American media, during the insurrection chose to glorify and lionize Fidel Castro and his 26th of July movement, ignoring the exploits of the RD (13th of March movement).

There were major differences between the two groups of revolutionaries. The RD movement was decidedly anti-communist and would not allow communists in its ranks. Castro’s 26th of July movement, as I have documented in Cuba in Revolution, was infiltrated by known communist subversives, beginning with Raúl Castro and Ernesto (Ché) Guevara, who percolated through the ranks.

Moreover, the 13th of March movement had a joint leadership, which deliberated on the conduct of the war and policy matters. From the beginning, the 26th of July movement was led by a megalomaniac autocrat with strong fascist tendencies, Fidel Castro, who did not like to have his authority questioned. As I recount in my book, those who challenged his authority did not survive the revolution.

Who made up the RD? They were students, professionals, workers, and peasants, who courageously fought against Batista in the streets of the larger cities using urban warfare tactics and in the countryside in the Escambray Mountains of my own Las Villas province using guerrilla operations.

The RD received immediate but fleeting notoriety when on March 13, 1957, it launched the heroic and valiant, yet also suicidal, attack against the Presidential Palace, President Fulgencio Batista’s ornate palatial fortress in Havana. It was organized by José Antonio Echeverría, student leader and head of the RD. The determined band of insurgents included virtually the entire leadership of the Havana underground group.

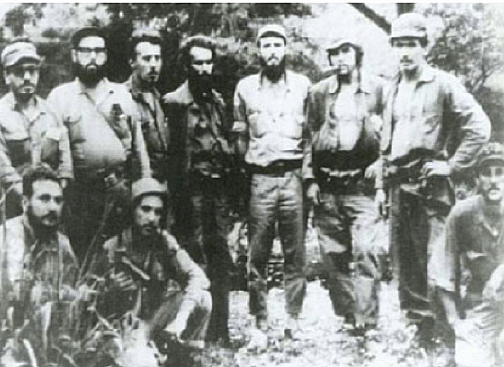

Nevertheless, the audacious attempt at “striking at the top” and executing Batista failed. The majority of the assailants died in the attempt and so did most of the leadership. The surviving leader, Faure Chomón, escaped and was sheltered at my parent’s home in Sancti Spiritus for over two weeks. His code name was “Ricardito.” I remember playing soldiers with him as a child, and I missed him when we finally took him to join Comandante Rolando Cubela in the nearby Escambray Mountains. My uncle Julio (center figure in photo below) followed Faure later and joined Cubela’s fighting group.

Had we been found out as being part of the revolutionary underground, my parents would have been tortured and executed by Batista’s esbirros (political police).

The storming of the Presidential Palace in the nation’s capital, Havana, in broad daylight by the Directorio was the most dramatic and heroic act of the entire insurrection against Batista. But surprisingly, it got short shrift in the American press, silenced by the utterances of Fidel Castro in the lush shelter of the Sierra Maestra in the faraway Oriente province. As I wrote in Cuba in Revolution:

“It is of interest that despite the dramatic gesture and the valiant exploits of its members, both as a feared, urban underground organization and guerrilla army in the rugged Escambray Mountains, the RD never aroused the curiosity of the American media, particularly those who took a liking to and repeatedly glorified Fidel Castro.

Foremost among them was Herbert L. Matthews of The New York Times, but there were also many other influential journalists in this camp who lionized Fidel Castro from his earliest days as a revolutionary while writing for such noted publications as Newsweek, Life and Time magazines.”

You also discuss the little-known revolts against Communist Cuba such as the Escambray Rebellion.

Yes, Myles, the 1960-1965 wars of national liberation against Castro-communism in the Escambray Mountains is another lost chapter of Cuban history, particularly for American readers. We must thank my friend, the Cuban writer Enrique Encinosa, for documenting details about these forgotten wars that otherwise would have been lost. That heroic rebellion against Castro’s collectivist autocracy was led by a family friend and former RD comrade-in-arms, Osvaldo Ramírez, to whom I refer amply in my book.

Regarding this heroic rebellion, I wrote in Cuba in Revolution:

“The forgotten wars of the Escambray Mountains (1960-1965) viz., the repeated encirclements by the tens of thousands of communist troops deployed to annihilate the brave bands of anticommunist alzados and their repeated, heroic breakouts from these deadly encirclements; the capture and execution of prisoners, etc. were not reported by the U.S. media. The number of alzados reached roughly the same number, perhaps 3500 troops, as the combined Rebel Armies against Batista toward the end of 1958. Yet, there were no dramatic reports or audacious interviews with the legendary Osvaldo Ramírez, the fearless Luis Vargas, or the courageous Tomasito San Gil. In Cuba, there was censorship and eventually only the State-run Granma to report events, but where were Herbert Matthews, The New York Times, Newsweek, and the rest of the American media to recount the heroic exploits and interview the heroes of the Escambray Mountains?”

Could the Escambray rebellion have succeeded? Although the alzados in the Sierra del Escambray probably never exceeded 3,500 freedom fighters, Raúl Castro once admitted in a rare, candid interview that his communist force suffered 6,000 casualties at the hands of the alzados. These anti-communist rebels were valiant, fierce fighters, but they had virtually no outside help.

Imagine and I discuss this in my book if the failed Bay of Pigs invasion could have been coordinated with these heroic freedom fighters? It was around the time of the Bay of Pigs incident that the alzados were in fact nearing their peak of success. Imagine what the outcome could have been if such assistance and coordination had been rendered.

During the Escambray rebellion, a virtual genocide with relocation camps was conducted against the campesinos (peasants) who aided the alzados. The campesinos were willing to join the alzados to fight against Castro’s collectivist agrarian policies (state farms). But the limiting factor was always the number of arms that could be procured from a friendly population that had already been disarmed and was emigrating from the country in droves.

You write that “the Batista coup of 1952 was a walk in the park compared to Fidel’s communist Revolution of 1959.” You also note Fulgencio Batista’s repression and atrocities. Why aren’t Batista and Castro comparable tyrants in your view?

Batista’s coup d’état of March 10, 1952, was bloodless even though it triggered the cascade of painful events that would eventually bring Fidel Castro to power. Batista, for all his bad press and reputation, may be considered a “benevolent” despot when compared to the monster Fidel Castro.

Despite the atrocities committed by the Batista regime, no more than 1,000 to 2,000 deaths can be reliably attributed directly to his regime. The vastly exaggerated figure of 20,000 deaths that was floated around eventually was found by Bohemia to have been fabricated by Fidel Castro’s apologists. The more accurate figures pale in comparison to the figures amassed by Fidel Castro and his communist dictatorship.

Under the Maximum Leader’s totalitarian regime, half a million political prisoners have been forced through its jails, untold thousands have been executed or have died heinous deaths while in detention or incarcerated. Since Fidel Castro does not allow independent media sources to tally the regime’s figures, no accurate number can be cited for those who have died in his prisons.

What we do know with more certainty is that Cuba, with a population of 11 million people, has had under house arrest or in its sordid jails and prison camps an estimated 500,000 prisoners. Political prisoners are held in barbaric conditions in celdas tapiadas (small jail cells no bigger than a closet and without windows).

Dark and dreadful prisons such as Boniato, Combinado del Este, Cuba Sí, Prisión del Manguito, and among others, Nuevo Amanecer (New Dawn) and Manto Negro (Black Mantle) for women, as well as the notorious and gruesome dungeons of the converted Spanish colonial fortresses such as El Morro Castle, El Castillo del Príncipe and Fortaleza de la Cabaña bear witness to this barbarity.

Moreover, in today’s totalitarian regime, all Cubans are held as virtual prisoners and are not allowed to leave the country. Between 1960 and 1993, 36,000 Cubans perished at sea trying to escape Castro’s communist inferno. In the case of Batista, Cubans were free to leave with family and their wealth and personal possessions, anytime they wished. A would-be émigré only needed to purchase a one-way ticket to Miami or elsewhere.

Countless thousands of Cubans have died indirectly as a result of Fidel Castro’s collectivist policies, unspeakable privations, malnutrition, and the general desolation of a once prosperous island, a beautiful and bountiful island that Christopher Columbus called the “Pearl of the Antilles.”

Since Fidel Castro took over the island in 1959, the best figures we can glean are between 30,000 and 40,000 people who either have been executed en los paredones de fusilamiento (on the firing squad wall) or have died at the hands of their communist jailers. The scholar Armando Lago has arrived at a death toll of 105,000 victims directly attributed to the regime of Fidel Castro.

Yet if we use the higher estimates, all of those who died escaping the regime, were shot or in custody, the figure well exceeds 100,000. One day, like with the Soviet Union, we will learn the truth, and more accurate numbers will be available recording the full extent of the brutality and destruction wrought by communism in Cuba.

I thought one of the most interesting sections of Cuba in Revolution is your discussion of how, using registration lists created under Batista, the post-1959 regime confiscated firearms to consolidate its power.

Yes, that is indeed a Cuban lesson worth learning, an advice well-heeded by our fellow freedom-loving citizens of these United States. We learn from history that those authoritarian governments that conducted democides (i.e., killing of their own populations) during the 20th century first disarmed their citizens, eliminating private firearm ownership in the civilian population. Cuba was no exception.

After the triumph of the revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro reneged on his promise to establish democracy in Cuba. In response, the RD threatened another insurrection against the new revolutionary government. To back their demands with substance, or perhaps even expecting a showdown, the RD also seized arms from the San Antonio de los Baños Air Force Base.

Fidel, the demagogue, reacted in a speech at the Maestre Barracks of San Ambrosio and artfully commanded the situation by accusing the Directorio of seizing the arms and then, in a masterpiece of rhetoric, asking in his impromptu speech: Armas ¿para que? ¿Para luchar contra quién? ¿Contra el gobierno revolucionario, que tiene el apoyo del pueblo? (“Guns, for what? To fight against whom? Against the Revolutionary government that has the support of the people?”)

Fidel not only defused the situation but neutralized the defiance of the RD. Thereafter, he commenced his long-term campaign to disarm not only the members of the Revolutionary Directorate who did not join him but also, in due time, all Cubans. Shortly, a 100,000-member “militia” army was organized to seek out the political opposition and actively disarm it.

Unfortunately, they had a well-drawn blueprint to follow, the local firearm registration lists Batista had established. All the milicianos had to do was to seize the registration (licensing) lists and then go door to door, searching for and confiscating firearms.

I ought to know. An uncle, who shall remain nameless, worked at the public records office in the ayuntamiento (City Hall) in Sancti Spiritus, where my hometown’s registry was kept. They came to our house. But to find out what happened when they tried to disarm my father, you will have to read the book!

Be that as it may, the term “militia” in the American experience had been turned upon its head in Cuba. In the U.S. Constitution, the “militia” is every able-bodied man of military age, the whole people, which potentially could be mobilized as a bulwark against tyrannical government. For that purpose, the citizenry have an individual right to keep and bear arms.

In the Cuban experience, the revolutionary workers/peasants “militia” became an arm of the government, not only to reinforce the military but also, most ominously, used to disarm their recalcitrant neighbors, provide surveillance and enforce the dictates of the emerging police State.

Read: Interview With Dr. Faria, Part II

Myles B. Kantor is a columnist for FrontPageMagazine.com, a popular internet website edited by David Horowitz. Mr. Kantor is also Director of the Center for Free Emigration, a human rights organization dedicated to the abolition of State enslavement. His e-mail address is kantor@FreeEmigration.com.

This article may be cited as: Kantor MB. An Interview with Dr. Miguel Faria (Part I). Newsmax.com, June 14, 2002. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/interview-with-dr-miguel-faria-part-i-by-myles-b-kantor.