- Articles

Cuban War Criminal Touring U.S.

Víctor Dreke and the Real Story of the Escambray Wars

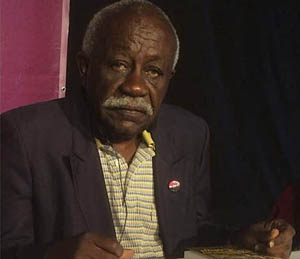

On Nov. 13, 2002, Víctor Dreke, a Cuban Communist Party official, and a man accused of committing war crimes during the Escambray wars of the early 1960s in Cuba, spoke at a North Miami forum hosted by Florida International University.

According to the Miami Herald, although there were protests outside the ballroom where the forum was held and a handful of Cuban exiles within shouted asesino! (“assassin”), the majority of the crowd offered a standing ovation to the communist official!

But the affair does not end there.

Incredibly, Dreke’s special visa allows him to stay in the U.S. through the end of this month, touring the country sharing his “historic experiences” and promoting his book, From the Escambray to Congo: In the Whirlwind of the Cuban Revolution, published last year in both English and Spanish by Pathfinder Press. Could you imagine exiled writers such as Guillermo Cabrera Infante (Mea Cuba), Enrique Encinosa (Cuba en Guerra) or Juan Clark (Cuba: Mito y Realidad) touring Cuba and promoting their books in the very belly of the totalitarian beast?

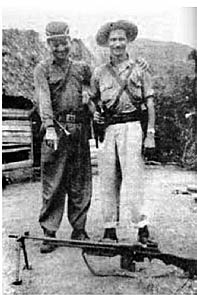

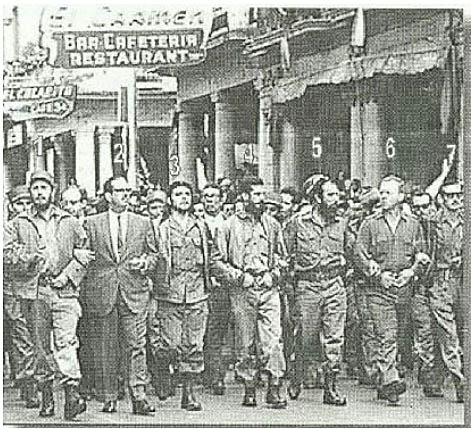

Who is Comandante Víctor Emilio Dreke Cruz? He was Ernesto “Ché” Guevara’s second in command in the ill-fated military expedition to the African Congo in 1965, as well as one of the commanders of the so-called Lucha Contra Bandido (“War Against Bandits”), a genocidal war waged against the anti-communist campesinos of the Escambray mountains in Las Villas province. (1)

A Cuban government Web site declares that on July 8, 1999, Dreke testified in Havana at a “popular provincial tribunal” that indeed he fought in the Escambray wars against the “CIA-backed” anti-communist “bandits” (the alzados) and goes on to describe his “heroic” exploits in that drawn-out sanguinary genocidal war to impose communist rule over the rural population of the area.

At the Cuban government website he goes on to repeatedly call the campesino anti-communist rebels bandidos (“bandits”), as Fidel Castro preemptively decided to demonize them before launching his overwhelming communist offensive.

But the campesinos turned out to be hard nuts to crack, and it took more than six years (1960-1966) and over 6,000 communist casualties before the heroic rebels were crushed by overwhelming communist forces. (2)

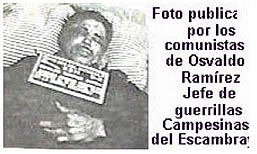

Rather than being “bandits” and “instruments of a policy of sabotage and terror” financed by the U.S. government and backed by the CIA, as Dreke described them, the anti-communist alzado rebels, who operated in the Escambray mountains of my native Las Villas province, were mostly humble campesinos (peasants), led not by Batistianos but by former revolutionaries of the 13th of March Revolutionary Directorate (RD) movement, like the valiant Osvaldo Ramírez, who fought against Batista but later felt betrayed by the Revolution.

For most of the revolutionaries of the anti-communist RD movement, Fidel Castro’s Marxist revolution was a profound betrayal of the insurrection against the former dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Like the kulaks of the former Soviet Union exterminated by Red Czar Joseph Stalin during the 1920s and 1930s, the alzados were campesinos and guajiros (rural people) who rebelled and fought the communist troops that had, at the point of a gun, taken their land and forced them into collective farms in the name of agrarian reform.

As I wrote in Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (page 106): “…Towards the end of 1961, Law 988 decreed that by virtue of being ‘outlaws,’ alzados forfeited both their lives and their property, and could be shot on sight or fusilados if apprehended.”

It’s well known that between 3,500 to 5,000 alzados (and campesino sympathizers) were killed in the bloody Escambray wars (casualties mounted on both sides particularly during the sanguinary year of 1963 that the regime itself called the Año del Cuero Duro, “the Year of the Tough Hide”) or executed after their capture by the communist regime. In fact, these figures are in agreement with communist apologist writers like Norberto Fuentes, who remains friendly to the ideals of the totalitarian regime.

Dreke himself participated in the ghastly execution of alzado leader Margarito Lanza Flores (Tondike), a black Cuban. Tondike was surrounded by communist forces in a sugar cane field, which was set ablaze. Tondike tried to dig his way out to escape the flames, only to be savagely burned and apprehended. Without having medical assistance rendered, he was pulled to the side of a creek and summarily executed by Dreke, another black Cuban.

Dreke mentions a number of “crimes” committed by the alzados, ignoring the greater crimes of the communist dictatorship. He mentions U.S. assistance to the anti-communist rebels and even calls them “bandits,” “the military arm of the CIA,” when in fact the aid rendered to the rebels was scanty, few and far between, almost nil.

Following the Bay of Pigs debacle and the missile crisis incident, as I wrote in Cuba in Revolution (page 418): “Minimal assistance came from the U.S. via the CIA because of policies emanating out of ‘plausable deniability’ and the Kennedy-Khrushchev pact, which prevented U.S. assistance to the freedom fighters. Again and again, the intrepid rebel leader, Commander Osvaldo Ramírez, had to turn away new alzados because of lack of arms and equipment.”

The limiting factors in the Escambray wars were insufficient and inadequate U.S. assistance and the lack of arms and ammunition that could be supplied by the Cuban populace, which had been disarmed.

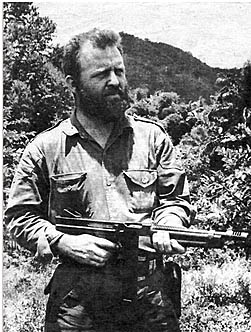

Dreke mentions alzados as the “bandits” and “Tomassevich” as the hero in the same breath. There was no greater bandit in the whole Escambray rebellion than Comandante Raúl Menéndez Tomassevich. Tomassevich was imprisoned in 1955 for trying to cash bad checks and perpetrating fraud. After his release, he joined Castro’s 26th of July movement, where his penchant for crime and violence paid off as a revolutionary with a cause.

Dreke mentions William Morgan in passing and takes another opportunity to blame the [American] “imperialism” for the “counterrevolution.” Comandante Morgan was, in fact, a brave American who took up the Cuban cause for freedom, another 13th of March RD (later “Second Front”) revolutionary, who “fought for the Revolution but not for communism.” I described his end in Cuba in Revolution (page 107):

“Comandante William Morgan, an American adventurer who had found his calling with the RD in 1957, was implicated in an assassination attempt against Fidel Castro and executed in 1961 in Fortaleza de la Cabaña. … Morgan did not make it to the paredón de fusilamiento (firing squad wall). With Fidel and Raúl Castro present, the RD commander was told to get on his knees and plead for his life. He responded firmly and without hesitation, ‘I don’t kneel in front of any man.’ A communist captain then shot him in both knees to forcibly prostrate him. When Morgan tried to get up, he was shot in both shoulders. He exsanguinated without ever reaching el paredón (the wall).”

Morgan is the type of man that Dreke vilified in the service of the communist regime. Why was Morgan “implicated”? Because among other things, he declared he was not a communist.

Suffice to say that the communist Dreke was one of those who accompanied Ernesto (Ché) Guevara on his ill-fated expedition to the African Congo. One of the many ironies of the Congolese debacle was that while the expedition was led by a white Argentinian, the group was composed mostly of black Cubans like Dreke and Henry Villegas Tamayo (“Pombo”). (Villegas was to follow Ché Guevara to Bolivia in 1966, the Argentinian’s greatest and final debacle.)

The black Cubans were horrified to see their Marxist African brothers practicing cannibalism in the midst of warfare ferociously devouring the liver, heart and other body parts of the fallen enemy.

Not only were the Cubans beaten and scattered in the African jungle, but the 58th Company commando unit of “Mad Mike” Hoare, the legendary British mercenary, and Rip Robertson of the CIA was made up of exiled anti-communist Cubans. (3)

And as I discussed in Cuba in Revolution (page 250-251): “In the 1960s, when Ché Guevara abandoned his defeated troops in the Congo near Lake Tanganika, [Major General Arnaldo] Ochoa was there to pick up the pieces and bring the deserted troops back to Cuba. …” The highly decorated Cuban general and war hero would be executed in 1989 as a scapegoat to shield the Castro brothers against allegations of drug trafficking. (4)

Because Dreke is a black communist, he is now being paraded around the U.S. as an opponent of racism and a promoter of human rights, touting “Cuba’s contribution to the welfare of native Africans and Afro-Cubans.” He is not being asked to explain the anticivil rights and unjust imprisonment of Vladimiro Roca, Dr. Oscar Elias Biscet, Jorge Luis Garcia Perez (“Antunez”) and hundreds of other black Cubans who have spent years in prison because of their yearning for freedom.

Such is the state of U.S. academia today that Dreke, a communist and accused war criminal, has been converted to an intellectual and his revisionist book, From the Escambray to Congo: In the Whirlwind of the Cuban Revolution, hailed as a great work of history.

Defending his invitation to Dreke to speak at a forum in Miami, Florida International University President Dr. Modesto A. Maidique wrote:

“My role as the president of FIU obliges me to protect and defend the right of faculty who have invited these emissaries from Cuba to speak on our campus. Our faculty at FIU have autonomy through academic freedom, to invite whomever they see fit, even when the President and the administration of the university are not in agreement with the ideas the guests may espouse. I call upon all in the community to understand and respect the liberties that this country offers to us.”

Knowledgeable citizens are not convinced of Dr. Maidique’s sincerity. Jorge Maspons of New Orleans, Louisiana, wrote him: “Mr. Dreke is a criminal who should be put on trial after the liberation of Cuba. … I am a proud American Vietnam veteran. You can be assured that this action is an insult, not only to me, but to all American war veterans who went to combat to exterminate subjects such as Mr. Dreke.”

And Rosa C. Novellas-Bengochea of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, replied to Dr. Maidique: “[My opposition to the invitation] was never a matter of different or opposing ideas; we respect and defend the rights of others to disagree. We are law-abiding citizens that fled oppression and came to the United States, our home, in search of liberty, justice and the rights that were denied to us by a totalitarian regime. Many were not so lucky and were taken to the firing squads by your guest for simple dissent. How can you place the fear of losing your job and role as president [of FIU] in front of ethics and principles?”

Yes, such is the state of ethics and politics of the Ivory Tower of academia even after the collapse of the USSR that the modern-day academician-alchemists continue in their quest to transmute the white creamy color of the elephant tusk into the bloodied red color of Marxism.

References

1. Faria, MA Jr. Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise. Macon, GA, Hacienda Publishing, Inc., 2002, p. 88-104.

2. Ibid., p. 105-115.

3. Encinosa E. Cuba en Guerra: Historia de la Oposición Anti-Castrista 1959-1993. Miami, FL, The Endowment for Cuban American Studies of the Cuban American National Foundation, 1995, p. 171-175.

4. Faria, op. cit., p. 250-255.

Written by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D., author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002; ) and Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS), is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.), Mercer University School of Medicine.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Cuban war criminal touring U.S. NewsMax.com, November 18, 2002. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/cuban-war-criminal-touring-u-s/

Copyright ©2002 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Cuban War Criminal Touring U.S.”

Watch this video from the PBS award-winning series American Experience, titled “American Comandante, Chapter 1,” to learn more about William Morgan: https://www.pbs.org/video/american-experience-american-comandante-chapter-1/?fbclid=IwAR113rTbKKv5xmboZI2ilTAFufPBZmtnCyXMjxqyG8PDP2U2tacn3AEqtNw