- Articles

Antony and Cleopatra — The Battle of Actium and the End of Hellenistic Egypt!

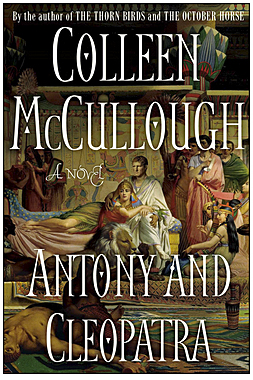

Antony and Cleopatra is the seventh and final book in the “Masters of Rome” series of historic novels by Australian author Colleen McCullough. This tome covers the years 41-27 B.C. of the late Roman Republic. At 567 pages, it is shorter than the previous books in the series. Gaius Octavian, now calling himself Caesar Octavianus, divi filius contends with his fellow Triumvir, Marcus Antonius, and Antony’s lover, Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt.(1)

In all of her books of this series McCullough’s characters speak in a modern tone (which at times becomes needlessly vulgar). Characteristically, she makes no attempt to have speakers sound Shakespearean or archaic, but in this last tome, she is a bit more chatty, uses more dialogues, and is generally less informative of other historical events taking place contemporaneously. We are basically in tune, almost exclusively, with the fewer main characters left standing following Rome’s civil wars, battles, and proscriptions.

Events covered in this tome include: events following the defeat and dramatic suicides of Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus after the Battle of Philippi in 42 B.C.; the ensuing rivalry of Marc Antony and Octavian; the control of the seas and depredations of Sextus Pompey on Roman grain shipments; the land and maritime victories of Octavian’s alter ego, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa; the naval defeat of Sextus Pompey, Pompey’s youngest son, and his death, the last of the great Republicans; Marc Antony’s misadventures in the East and his debacle expedition against the Parthians; Antony’s emotional deterioration and dependence on Cleopatra for money, supplies, and moral support; Octavian’s pragmatic and ruthless political partnership with his ambitious wife, Livia Drusilla; Antony’s divorce of the revered Octavia and the reading of his “treasonous” will by Octavian in the Roman Senate; the downfall of the Second Triumvirate and war in 33 B.C.; the shameful but decisive defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC; the invasion of Egypt by Octavian in 30 B.C. with the defeat and suicide of Antony; the conquest of Alexandria, and capture of Cleopatra, who also commits suicide; and the complete victory of Octavian, who in 27 B.C. is honored with the title “Augustus” by the Roman Senate.

Antony and Cleopatra is a better book (4 out of 5 stars) than McCullough’s three previous volumes dealing with Julius Caesar, simply because she is not dealing with her idol.(2-4) We are spared the continuous praise and adoration of the demigod, who both the people of Rome and McCullough deified. We are at intervals, but not repeatedly, reminded of Julius Caesar’s greatness and the insignificance of every other Roman, except Antony and Octavian. And so, we are thankful to deal with the conversational tone of this volume and the twists and turns of the tempestuous love and political affair of Antony and Cleopatra. In fact, the psychological portrayal of McCullough of this famous couple is plausible and supported by historic evidence. Although supported by the coinage I have seen of the Queen of Egypt, Cleopatra’s physical appearance, that of a small, shriveled shrew of a woman is hard to conceptualize. Be that as it may, she seduced Caesar and then Marc Antony, the latter to a fatal degree. She is also portrayed as an intriguer and ambitious but inept ruler, who nevertheless controls Antony. All her cunning employed to gain for Caesarian, her son with Julius Caesar, the throne of Egypt and Rome! Antony is susceptible to her machinations because he has lost his self-confidence and his dignitas, after Caesar’s will named Octavian, and not him, as heir to Caesar. He had also failed to stop a 19-year-old from gaining power and becoming the First Man of Rome.

But now we are treated to Caesarion, who like his father Caesar, is a perfect youth — tall, blond, beautiful, brilliant, idealistic but extremely wise, even before he reaches his teens! Two-thirds of the way through the book, McCullough lapses into absurd adoration of Caesarion, Ptolemy Caesar Pharaoh. And Cleopatra, returning to Alexandria after a one-year absence, finds the youth drafting legislation at age twelve: “Even forewarned, Cleopatra’s first sight of her son took the breath from her body…all of which was nothing compared to the likeness of his father…the sensuous mouth with the creases of humor in its corner — Caesarion, Caesarion!”(5)

Octavian is an imitation; Caesarion is the real thing, “a true prodigy, like his father…as a tiny baby in arms, he had talked in polished sentences; no one could fail to see what a mighty mind dwelled inside the infant Caesarion.”(6) At age twelve, Caesarion, as Caesar’s biological son and living image, is turned into another earthly deity, Eros and Apollo personified, but alas, only five years later at the time of final reckoning, he will lack at seventeen, the wiles of Ulysses (or Octavian!) and the attributes of Mars. Destiny and history get in the way of McCullough’s novelistic love affair with Caesarion, as they did with Julius Caesar, and Caesarion is captured and dramatically stabbed to death by Octavian himself in his commander’s tent.

For McCullough the Republic was a dead end. It needed to be overthrown and an empire created ruled by autocracy and the enlightened despotism of Caesar and his godly descendants supported by the adoring masses, sharing the wealth of the empire. It is ironic that elsewhere McCullough had commented that fathers are very frequently succeeded by dangerous mediocrities, most derisively in the hated families of the Roman nobility, but she does not see it in the case of Caesar; as in fact it happened two generations later with the bestial reigns of the Julian Emperors, Caligula (A.D. 37-41) and Nero (A.D. 54-69). It is true that by 30 B.C. and the triumph of Octavian, the Republic was exhausted and the Roman nobility decimated by civil wars and proscriptions. And yet, it was the semblance, conventions, and forms of the old Republic within the later Empire that might have kept the empire thriving with relative freedom and prosperity, despite the monsters Caligula, Nero, and Domitian, until the strangulation death of the brutal Commodus (A.D 180-192).

In the view of McCullough, Republican rule was satisfactory for small city states, but autocracies are better for larger empires. I wonder where that leaves the constitutional monarchy of Great Britain (more akin to Republican rule than autocracy) in the last three centuries and the United States in the 20th and 21st centuries? These are the true types of enlightened self-government that brought liberty and unprecedented prosperity to millions of people throughout the globe, including McCullough’s native Australia. We are surprised, though, that toward the latter part of the book, for the first time in this series, McCullough used the word “democracy” (people’s rule), a Greek concept and word the Romans did not use, preferring res publica, for republic and the rule of laws (“government in the public interest”).(7)

McCullough has an interesting theory that at the naval Battle of Actium, the flight of Cleopatra, followed by that of Antony, was planned, as the rulers of the East recognized they have been outmaneuvered by Octavian and Agrippa. They had been pinned down in the Bay of Ambracia, their fleet trapped, supply bases lost, their land army abandoned. Their plan was to flee to Alexandria, reorganize their forces and take a stand there on Egyptian soil.(8) But the stand in Alexandria was another debacle, more defeats, non-events, accentuated by the desertion of Antony’s last forces, and the suicide of the hen-pecked renegade Roman general, Marc Antony, and the “Queen of Beasts,” as Octavian called Cleopatra.

The denouement of Caesarion finally meeting Octavian is well thought out in terms of preserving Caesarion’s courage and equanimity in the face of death, but it casts doubt on Caesarion’s “brilliance” and political judgment. Caesarion only reaches understanding after Octavian clearly and dispassionately explains why he, Caesarion, must die, as a living threat to Octavian’s long fought ascendancy to power and security. Neither the adoring Cleopatra, for whom Caesarion was everything, or Antony, his guardian who also promoted Caesarion’s cause, properly advised Caesarion of the danger of presenting himself to the ruthless and pragmatic Octavian. It is ironic then that Caesarion, wise beyond his years, did not recognize in his own mind the danger he faced, “as living image of Julius Caesar,” and instead of escaping to India as planned, he naively marched to meet and bargain with Octavian! The result was he learned he must die and met haplessly his fate. It is reminiscent of McCullough’s dealing with the fate of “his father” Julius Caesar.

McCullough never recognized for all of Caesar’s political brilliance and “wisdom,” because of his vaingloriousness, his hubris, his unquenchable thirst for political power, his trampling of the mos maiorum, that he never understood how much he was resented by patriots as well as by moderate men. Sixty Roman knights and senators participated in the conspiracy and no one talked — and then in a final and ironic twist of fate, Julius Caesar fell and died at the base of the statue of Pompey the Great!

Read Dr. Faria’s review of the previous installment of McCullough’s “Master of Rome” series.

References

1) McCullough C. Antony and Cleopatra. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 2007.

2) Faria MA. The October Horse — Civil War in Ancient Rome and the Death Knell of the Republic. A book review of The October Horse (2002) by Colleen McCullough. Haciendapublishing.com, Nov. 17, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-october-horse–civil-war-in-ancient-rome-and-the-death-knell-of-the-republic.

3) Faria MA. Caesar’s Women — McCullough’s Idolatry and Politics in Ancient Rome. A book review of Caesar’s Women (1997) by Colleen McCullough. Haciendapublishing.com, August 14, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesars-women-mcculloughs-idolatry-and-politics-in-ancient-rome.

4) Faria MA. Caesar — The Conquest of Gaul, Civil War, and the Death of Pompey the Great. A book review of Caesar: Let the Dice Fly (1997) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, October 6, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesar–the-conquest-of-gaul-civil-war-and-death-of-pompey-the-great.

5) McCullough C. Antony and Cleopatra. Op. cit., p. 354-355.

6) Ibid., p. 360

7) Ibid., p. 438

8) Ibid., p. 473

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria, Jr., a medical historian, is the author of Cuba in Revolution — Escape from a Lost Paradise (2002) and of numerous articles on politics and history, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011), The Political Spectrum — From the Extreme Right and Anarchism to the Extreme Left and Communism (2011); Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery (2013), etc., all posted at his website HaciendaPublishing.com. He has reviewed all seven volumes of McCullough’s Masters of Rome series.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Antony and Cleopatra — The Battle of Actium and the End of Hellenistic Egypt! HaciendaPublishing.com, November 28, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/antony-and-cleopatra–the-battle-of-actium-and-the-end-of-hellenistic-egypt.

(Antony and Cleopatra by Colleen McCullough (2007). Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 567 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s Antony and Cleopatra. They are added here for the enjoyment of our readers. An unillustrated version of this article appeared also in Amazon.com book reviews.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

1 thought on “Antony and Cleopatra — The Battle of Actium and the End of Hellenistic Egypt!”

The aristocratic Roman Republic achieved the conquest of the Western world, halted the barbarian hordes, constructed engineering marvels, such as bridges, roads, and aqueducts, codified magnificent laws, and lasted 5 centuries in which Roman citizenship was coveted and treasured, civilization spread, and commerce flourished. Even after Augustus triumphed nearly a century later, the forms (although not the substance) of Republican government with consuls, Senate, divided powers, etc. were maintained and lasted another 300 years.

Otherwise how does one explain five centuries of incredible expansion and military and political brilliance unprecedented in history? One wonders how the Roman Republic grew so rapidly into a land and maritime empire that conquered the Western world; kept the vast barbarian hordes at bay; created a civilization with incredible marvels of engineering, bridges, roads, sewers, aqueducts, monumental architectural wonders; and debated and promulgated magnificent laws. And then transferred these achievements to an Empire that continued to prosper for centuries, at Rome and later at Constantinople. The Roman Empire continued to marvel at the earlier Republic and thus preserved at least in appearance, if not in substance, the semblance of Republican governance with figure head senators and consuls —and the preservation of the rule of law. The Roman Empire then kept the Pax Romana from the 1st century through the 3rd century A.D. After the Fall of Rome, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire centered in Constantinople provided a defensive and geographic bulwark that protected Europe from plundering Eastern barbarian hordes for another millennium until it fall in 1453.