- Articles, Recent

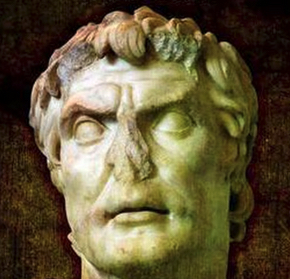

Sulla as Military Commander in the East (88-82 BC) by Miguel A. Faria, MD

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BC) was a patrician aristocrat who entered the army under the general Gaius Marius. In the Roman war against Numidia in North Africa, Sulla was instrumental in defeating the Numidians and capturing their king Jugurtha. In the Germanic invasion of the Teutons ad Cimbrians, Sulla again distinguished himself under Marius. Both men fought in the Social War in which Rome vanquished the Italians. Subsequently, though, the two generals parted company and became bitter enemies—Marius favoring the populares; Sulla, the optimate political faction. In the coming war against Mithridates VI, King of Pontus (r. 120-63 BC), who had encroached against Roman territories and massacred thousands of Roman civilians, both Marius and Sulla sought command of the army but Sulla, who was the consul for 88 BC, prevailed and was sent to Greece to settle scores with Mithridates. With Sulla gone on his expedition, Marius and his ally Lucius Cornelius Cinna returned to Rome, seized power, and wreaked vengeance against their enemies, real or imagined.

Cinna and Marius made themselves consuls for 86 BC. Marius finally had achieved his prophesized and coveted seventh consulship. Still consumed by fury, committed atrocious crimes during the thirteen days of his consulship, but then he suddenly succumbed to a stroke and died. Exceeding the political crimes of the Cinna-Marius faction, Marius’ retinue of murderous ex-slaves had been free to rob and rape the populace until Quintus Sertorius had their encampment surrounded in the night, and every one of them killed.

Sulla had left Rome in a precarious situation. According to the senate, he was the lawful consul leading his legions. But according to the populist leaders now in power in Rome, he was a hostis leading a rebel army. Sulla marched into Greece pushing aside the armies he encountered. He took Athens after a prolonged siege and defeated Ariston, the tyrant of Athens allied to the king of Pontus. He sacked the Athenian Port of Piraeus, but he spared other parts of Athens because of the city’s former glory.

Sulla and the First Mithridatic War (88–85 BC)

Throughout Greece the legions under Sulla’s command overran the armies of Mithridates and his Pontic-Greek general Archelaus. The Mithridatic forces, estimated to number between 60,000 and 120,000 men were composed of phalanxes, scythed chariots, and cavalry. At Chaeronea, Sulla allowed the Pontic army, particularly the horsemen and the scythed chariots, to assemble in the valley. With much pomp, loud bragging, shouting, and general jubilation, the army attempted to intimidate the undermanned Roman army. While some Roman legionaries remained busy, digging the ditches and deep trenches around their encampment that Sulla had ordered, others kept approaching the enemy, shortening the distance the perilous scythe-wheeled chariots could use to gain speed in an attack. Archelaus, the competent Greek general, not only had tasted the sharpness of the Roman steel in previous engagements but also recognized the danger his army faced against the determined Romans. Yet, he was pressed by his fellow commanders to begin combat. After the attack began, he saw his chariots derailed and destroyed on the palisades. The phalanxes were caught in the field and destroyed by the tactical placement of the Roman artillery. Supported by the Roman cavalry, the legions then attacked both Pontic wings. Sulla went from one side to the other wherever reinforcements were needed and to encourage his men. In the end the Romans routed the Pontic army, which suffered a great number of casualties. “Sulla later wrote that he had only fourteen of his soldiers missing and that two of those men returned to their camp later that night.”

The next major encounter took place at Orchomenus where general Archaleus and his new reconstituted army came upon a beautiful plain, where he thought the flatter terrain would be more advantageous for his forces. But Sulla had already scouted the same area and found it ideal for his innovative construction of entrenchments and ditches to defend against a numerically superior army. This time, however, Archelaus ordered the attack before the Romans completed the ditches and entrenchments. The Romans were caught off guard, including the soldiers protecting the working legionaries. Despite the protection of their earthworks, the Romans found themselves hard pressed. Historian Lynda Telford explained:

One military tactic that served Sulla well was to dig ditches and earthworks on each side of his army, forcing the enemy to meet him head on and preventing their large number swirling about his flanks. At Orchomenus, in Greece, he was hard-pressed by the sheer numbers of the enemy. Seizing a standard, Sulla rallied his retreating men by shouting, “I am prepared to get the glory of fighting and dying here. As for you men, when they ask you where you betrayed your general, remember this place and say Orchomenus.”

After rallying his men, the Romans repelled the Pontic cavalry, and then went on the offensive, regaining their trenches and resuming their work.

Archelaus, once again, saw his opportunity and attempted to use his scythe-wheeled chariots. He thought the center of the field was clear and ordered another attack. His chariots formed the first line, and the phalanx formed the second line. The third line was made up of his auxiliaries that included Italian deserters who were expected to fight desperately given what their fate would be if they were captured by their countrymen. The Mithridatic army attacked with scythe-wheeled chariots, but these were channeled into paths riddled with stakes where they were entangled and destroyed by the Romans.

The Pontic army, partially destroyed, retired from the field, again leaving a large number of casualties behind, and returned to their camp for the night. The Romans, on the other hand, did not stop working. Sulla ordered the digging of the trenches to continue throughout the night. Thus, while the Pontic army slept, the Romans continued their labor.

The next morning Archelaus discovered that his whole camp was under siege. The Roman circumvallation, which was about 600 yards away, now trapped the Pontic army inside their camp and prevented further use of the chariots. In a desperate attempt to escape the Roman encirclement and the battlefield entrenchments, Archelaus hurled his army at the Romans. The Pontic army was destroyed attempting to break through the thick hedge and impenetrable barrier of Roman short swords. The slippery Archelaus, as he had done once before, escaped by boat to Chalcis.

Gaius Marius had received credit for his purported revitalization of Roman weaponry and tactics, but it seemed that Sulla had not received the full credit he deserved for his innovative use of encircling ditches and the construction of battlefield entrenchments that allowed a small army to defend itself against a much larger and better-equipped force. Julius Caesar used a similar method at Alesia and has received universal praise since that time. Moreover, encirclements and trenches have continued to be used from antiquity to very nearly our present age.

With the defeat of his armies in Greece and the loss of such a great number of men, Mithridates decided it was time to withdraw from the conflict. The Peace of Dardanus ended the First Mithridatic War under terms dictated by Sulla in 85 BC: The king of Pontus had to withdraw from all conquered territories and leave the Province of Asia and Paphlagonia in Roman hands. Mithridates had to surrender his navy and pay Rome a war indemnity of two thousand talents. If he agreed to and honored the terms, Mithridates would remain king of Pontus and keep his former Pontic possessions.

Cinna’s Commanders Dispute Command and Lose It All

Lucius Valerius Flaccus was elected suffect consul following Marius’s death in 86 BC. Towards the end of the year, the consul departed Rome with his legate and quaestor, Gaius Flavius Fimbria. With two legions, which historians refer to as the “Valerians” and “Fimbrians,” Flaccus was to assume command of the Roman army that Sulla, as a supposedly proscribed outlaw (hostis), was to yield to him. Since Sulla was now in Asia Minor, Flaccus marched the armies east along the Via Egnatia, constructed by the Romans in the 2nd century BC and linking Illyricum, Macedonia and Thracia along the coast to the village of Byzantium.

However, Fimbria soon began to intrigue, plot, and undermine his commander’s authority. The disloyal legate quarreled with Flaccus. Previously, Fimbria had been cavalry prefect for Cinna and one of the most bloodthirsty popular leaders during the brief but savage civil conflict in Rome in 87 BC. As Flaccus crossed the Hellespont to Asia with his Valerian legion, Fimbria and his rear guard Fimbrians launched a full-scale mutiny. Flaccus was assassinated and his head thrown into the sea. The soldiers, who were now under the command of Fimbria, were allowed to plunder and loot the land as they marched. When Fimbria entered Ilium (ancient Troy), he plundered the city, massacred the inhabitants, and then burnt the place to the ground. His cruelty remained notorious with the people of Asia Minor.

After successfully concluding the Peace of Dardanus, Sulla turned his attention to the Fimbria. Moreover, he had by now learned of the happenings in Rome and was eager to return to settle matters there. Sulla audaciously marched on Fimbria’s camp and persuaded the legionaries to defect. The infamous legate next plotted to assassinate Sulla. When the attempt failed, Fimbria committed suicide.

Conclusion: Sulla Returns and Takes Power in Rome

In 85 BC, Cinna selected Gnaeus Papirius Carbo to be his co-consul, and the two men began preparing for the impending confrontation with Sulla. They stockpiled supplies and began an intensive recruitment effort in Italy. They even spread false propaganda claiming that if victorious, Sulla would disenfranchise the new Italian citizens.

To counter Cinna’s claims, Sulla sent a dispatch to the senate describing his accomplishments in Greece and Asia. He also denied planning the disenfranchisement of the Italians. Ominously, Sulla affirmed that he would avenge the death of his murdered friends and punish those who persecuted and forced his family into exile. He swore he would also restore law and order. The Eternal City prepared for war.

Indeed, Sulla returned victorious and in a series of battle engagements wiped out the Marian popular faction. He was confirmed dictator, restored the power of the Senate that had been crippled by the populares, and reorganized the state according to the old laws and traditions of the Republic, the mos maiorum. Having done so he abdicated the dictatorship, became a private citizen, and died in 79 BC while in retirement. Sulla’s public funeral in the Forum Romanum was unrivaled until that of Augustus Caesar in AD 14.

Written by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is Associate Editor in Chief world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI) and the author of numerous books. This article is excerpted from his newly released book, The Roman Republic, History, Myths, Politics, and Novelistic Historiography (2025).

Copyright ©2025 HaciendaPublishing.com