- Articles, Popular

The Political Spectrum (Part III) — The Extreme Right: Anarchism

Note: The article below written years ago served as a springboard for an Appendix on Anarchism in Dr. Faria’s book, Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions published in December 2024 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. The article was fully expanded, revised, and updated for the chapter in that book, which is frankly much improved. —Editor. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-0364-1560-0

Let us now discuss the more arcane, extreme and revolutionary, right-wing philosophy, namely anarchism. You may ask when and where in recent history have anarchist revolutionaries been successful? For the answer, we must travel back in time to Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). It was in Barcelona and surrounding districts that idealist anarchism flourished in the early period of the war as anarchists defended the radical Republican government that the communists also supported against the military insurrection of General Francisco Franco. At this point, let me recommend two fascinating references: Alexander Orlov: The FBI’s KGB General by Edward Gazur (2001) and Deadly Illusions: The KGB Orlov Dossier Reveals Stalin’s Master Spy by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev (1993).

The first book was written by retired FBI agent, Edward Gazur, who debriefed and protected Stalin’s NKVD General, Alexander Orlov, after Orlov defected to the United States following the communists’ defeat in the Spanish Civil War. The second book, Deadly Illusions, was written with the collaboration and approval of the KGB (i.e., when the Soviet KGB files were made available following the collapse of the USSR) during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin in 1993. Although the books are supposed to be at odds with each other in reference to General Orlov’s real loyalty, they totally agree on one point relevant to our discussion here — the elimination of the Spanish anarchists by their communist “allies” during the Spanish Civil War.(1)

To sum it up, the naive anarchists were exterminated by their communist “friends” and comrades as the war raged. Elimination took place by communist brigades of NKVD units working under Stalin’s orders. These units were sent to Spain to wipe out their anarchist allies as well as “leftist” Trotskyites, both of who were fighting their common enemy Franco. And in truth, the Soviet NKVD commandos liquidated their allies with more avidity than they fought the “fascist” forces of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Top Soviet NKVD generals, including Alexander Orlov, carried out the liquidation. This sanguinary and infamous chapter of communist treachery has been triply confirmed by KGB General Pavel Sudoplatov in his book, Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — A Soviet Spymaster (1994). (Incidentally, imitating his former enemy, Stalin assumed as his last official title, “Generalissimo,” just like his nemesis Francisco Franco!)

Toward the end of the Spanish Civil War (1938-39), which so many useful idiots in the International Brigades considered the epic battle between fascism and “freedom,” the communists had exterminated both the anarchists and Trotskyites from the “Republican” ranks, and they had done so with more treacherous courage and efficiency, frankly, than they displayed against General Franco and his military forces. And in the process, the Russian communists robbed Spain of the gold treasury accumulated over centuries of Spanish history!(1)

In Italy, no civil war was needed to liquidate the anarchist “threat” to totalitarianism. Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) crushed his former ally, anarchist Enrico Malatesta, as soon as he was no longer useful. Malatesta died miserably under house arrest imposed by his former friend, Il Duce.(2)

But before we relate the fate of the Russian anarchist revolutionaries who fought at times, side by side, with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and the radical Mensheviks and Bolsheviks during the 1917 Russian Revolution, let us provide a little historical background as to the term “anarchism.”

A Brief History of Anarchism

Russia was indeed the home of modern anarchism in the 19th century, and because of the institutions of serfdom and autocracy of the Russian Czars, the seeds of nihilism and anarchism fell on fertile soil. In its essence, anarchism is a political philosophy that espouses the beliefs that: (1) no government is best, and therefore the state should be abolished; and (2) traditional institutions are intrinsically evil and corrupt the inherent goodness in man.

In England in 1793, in typical British non-violent utilitarian fashion, communal anarchism was propounded by William Godwin, who believed in creating autonomous communes. In these idyllic communes men could be free to act without any restricting social arrangements and forge utopias of collective goodness.

Such was not the case in France where that same year some historians studying the chaotic days of the French Revolution and predisposed to finding political anarchism in those events, have mentioned Jacques Rous and Rene Hebert, leaders of the Enrages, as possible anarchists. But those two men preached class warfare, hatred and mob rule, not anarchism. Gracchus Babeuf has also been called an anarchist because of his fomenting unrest and calls for social justice. But in fact, Babeuf was a man of the left with more authoritarian and communistic ideas than anarchistic tendencies. Babeuf was a member of the “Conspiracy of Equals,” who wanted to eliminate private property rights and institute wealth redistribution. Louis Auguste Blanqui and Filippo Buonarotti were also radical men of the socialist left, not anarchists.

The next genuine anarchist to come out of the pages of history is the Frenchman Pierre J. Proudhon (1809-1865), a member of the Constituent Assembly after the 1848 Revolution. Proudhon preached non-violent mutualism. Believing in the goodness and ethics of men and opposed to the use of force, he contended that social progress would eventually make government utterly superfluous in the affairs of men.

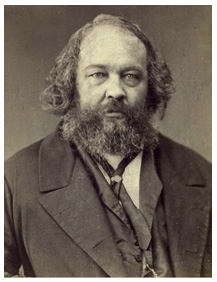

But now, we leave behind dreamy-eyed Western anarchists, and meet the father of modern anarchism, Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876), who believed that man was destined to explode in a spontaneous mass rebellion against authority. Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary as well as the greatest exponent of anarchism. He actually participated in the 1848 Revolutions in both France and Germany (Saxony). He made his way to London where he met Alexander Herzen (1812-1870), an exiled Russian socialist, and Karl Marx (1818-1883), a communist. In what can only be called the clash of the century between the ultimate Right and Left political philosophies, Bakunin clashed with Marx and was expelled (1872) from the International Workingmen’s Association. While Bakunin espoused the violent overthrow of the existing order, so that all men could live in absolute goodness and freedom, Marx, as we well know, espoused equal violence but directed in the class struggle, so that man in the form of the ruling, hated bourgeoisie would be overthrown and enslaved by the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Russian Anarchism in Literature as well as in Theory and Practice

In State and Revolution (1917), Lenin wrote: “The proletariat only needs the state for a certain length of time. It is not the elimination of the state as a final aim that separates us from the anarchists. But we assert that to attain this end, it is essential to utilize temporarily against the exploiters, the instruments, the means, and the procedures of political power, in the same way as it is essential, in order to eliminate the classes, as to instigate temporary dictatorship of the oppressed class.” The political reality was even more stark and sinister than could be expressed in his words. Lenin and later Stalin both justified the monopoly of power and even police state repression and the use of terror, that they arrogated to themselves and the Communist Party, by claiming to be the purported representatives of the proletariat!

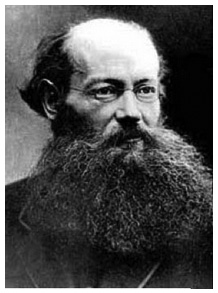

Even the Russian novelist and philosopher, Count Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) was thought by some to have dwelt on the fringes of anarchism, particularly as he aged, but the great author only preached spiritual non-violent revolution with “passive resistance to evil.” And, Prince Pyotr Kropotkin (1842-1921) enters the picture when there was such a streak of anarchism in Russia that it not only affected philosophers but princes as well!

Given the dilemma and conflict expressed between Marx and Bakunin (as well as by Lenin) — each aiming to overthrow states and governments either to create a utopia on earth with no government at all or a “classless society” under the pretenses of the dictatorship of the proletariat — it is no wonder that the thoughtful Prince wanted to reconcile the irreconcilable, communism and anarchism. So, how was this to happen? The state would disappear in a popular revolution.

Tolstoy did not live long enough to see his spiritual revolution. Kropotkin, though, did live long enough to witness the “popular” revolution, but not the emergence of the egalitarian utopia that he dreamt of for his native Russia. Nor did he witness the creation of a peaceful, happy, classless society, or even a true dictatorship of the proletariat, but instead the Prince witnessed the creation of a violent, sanguinary, totalitarian Bolshevik regime, headed by Lenin and enforced by Dzerzhinsky’s feared, repressive, omnipotent secret police, the Cheka. Prince Kropotkin did not like what he saw and although he was an almost iconic figure in revolutionary circles, he was powerless to stop the communist juggernaut and the hell-on-earth that would further emerge under Stalin. After his death in 1921, the fate of anarchism, like all other political philosophies in Russia, was doomed to extinction.

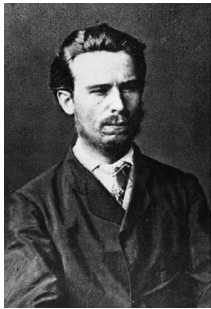

A prodigious disciple of Mikhail Bakunin was the nihilist-anarchist, Sergei Nechaev (1847-1882). Nechaev is an important individual in our story because he is not only a revolutionary and political theorist but he also bridges gaps between history and legend, and between legend and literature. Nechaev became the model for the main protagonist, Peter Verkhovensky, in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s (1821-1881) novel The Devils. The fictional character of Verkhovensky, a fiendish revolutionary terrorist, was inspired by Nechaev, in an instance of art imitating life. Nechaev had actually been tried and convicted of the murder of a fellow revolutionary by the name of I. Ivanov. This celebrated episode in 19th century Tsarist Russia is depicted in Dostoyevsky’s novel with the murder of Ivan Shatov. The character of Shatov is murdered — just like Ivanov was in real life — because he had turned his back on radicalism and revolution, and wished to return to his Russian Orthodox faith. Nechaev had become a legend in revolutionary circles, and now he was immortalized as a personification of evil in Dostoevsky’s novel.

The word “nihilist” was resurrected from ancient Greek metaphysics and applied to the Russian philosophy and political scene by Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883) in his masterpiece novel, Fathers and Sons, published in 1862. The novel’s title refers to the growing rift between two generations in mid-19th century Russia. And nihilism in the novel was used as a pejorative term inspired by one of the main characters, Yevgeny Bazarov, the young cynic who believed in nothing and exuded only utter contempt for the society and intelligentsia to which he belonged. Dostoyevsky went a step further with his characters in both The Devils (Stavrogin and Verkhovensky; 1872) and in Crime and Punishment (Raskolnikov; 1866)

Anarchists and Communist Revolutionaries

Sergei Nechaev was not only a terrorist, who founded the terrorist organization People’s Retribution, but he also considered himself a nihilist, so it is no wonder that in Russian cultural history the term “nihilist” has been linked to violent revolution and anarchism. The People’s Will (Narodnaya Volya), the successor terrorist organization to Peoples’ Retribution, to which Nechaev was associated even while in prison at the Peter-Paul Fortress, was responsible for the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881.(3) While some Tsarist prison conditions were harsh, exile in Siberia was relatively lenient for exiled revolutionaries.(4)

From the 1880s, anarchists became more and more allied to left-wing revolutionaries, believing they were on the path to creating a communistic utopia that would appear as soon as the state and societal institutions were destroyed. They mistakenly believed that an end to property ownership and the corrupting institutions of the bourgeoisie would usher in a Rousseauean, classless state with no need for government. However, the more organized, much better disciplined, and conspiratorial communists knew better. Nevertheless, anarchist and other terrorist organizations became more violent, not only preaching terror but also direct assassination, often with lethal success. In addition to the assassination of Russia’s Czar Alexander II in 1881, the Czar who emancipated the serfs in 1861, anarchists would claim responsibility for the following list of assassinations: the French President Carnot was stabbed to death in 1894; the Austro-Hungarian Empress Elizabeth was shot to death in 1898; and King Humbert I of Italy was assassinated in 1900. Anarchist violence even spilled over into the New World when U.S. President William McKinley was mortally wounded in 1901 at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Numerous other dignitaries including a Russian Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (1904) and Russia’s Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Phleve (1904) and Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (1911) would also be assassinated in the first two decades of the 20th century by successor organizations to both anarchists and the Peoples’ Will, primarily the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

As other revolutionaries formed organizations, or founded or join political parties, anarchists refused to organize on principle. Socialists and communists established political parties within the framework of established government institutions, but anarchists continued to refuse to do so. And yet, right-wing anarchists and left-wing socialists fought shoulder to shoulder against the existing bourgeoisie order in Russia. While the anarchists remained politically naive, the communists, particularly the always savvy but malicious Bolsheviks, understood the political nature of their “allies” and at heart considered them a counter-revolutionary movement that would require extermination once the Bolsheviks obtained power.

During the February Revolution of Aleksandr Kerensky (1881-1970) and the establishment of the Provisional government, the anarchists supported the Bolsheviks with the slogan “All power to the Soviets.” They also exerted a powerful influence upon the politics and militancy of the Kronstadt sailors, who were crucial to the Bolsheviks seizure of power.(3) But, the Bolsheviks’ systematic liquidation of their fellow anarchist “allies” would begin in April 1918 on the direct orders of Lenin and Trotsky, only a few months after the 1917 October (November in the new calendar) Revolution. The anarchist leaders were arrested, imprisoned or shot. Likewise, the Mensheviks and even the Bolsheviks’ closest allies, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Left SR), were purged. Needless to say, the Kadet Party (Constitutional Democrats) members of the Duma, who supposedly had constitutional immunity, had to flee and were hunted down. Lenin had already, within days of the triumph of his Revolution, issued a decree declaring the Kadets “enemies of the people,” a phrase that would be used more and more as the terror of the Revolution unfolded. Kadet leaders Shingarev and Kokoskin (1918) were located and killed in their hospital beds. Viktor Chernov (1873-1952), a leader of the Left SR, escaped but most other Left SRs were also hunted down and liquidated. And after an unsuccessful Left SR uprising on July 6, 1918 against the Bolsheviks (who had months earlier shut down the All-Russian Constituent Assembly) twenty Left SR hostages were summarily shot. The courageous Mariya Spiridonova, another Left SR leader, made no attempt to flee. She was arrested and sent to the gulag. She would remain toiling in the labor camps until 1941, when Stalin finally had her shot.

Conclusion

Let us now conclude the story of the anarchists. The Red Bolsheviks had not yet consolidated their power and were now locked in a life and death, bloody civil war struggle with the anti-communist Whites. In the Ukraine, Nestor Makhno (1889-1934) formed the anarchist Revolutionary Insurgent Army of the Ukraine to support the Bolsheviks during the period of 1918-1919. His anarchist army had fought Germans, Austro-Hungarians, then their Ukrainian nationalist brothers, and finally General Denikin’s White Volunteer Army. But none of this helped Makhno. True to communist form, Lenin and Trotsky turned against their former “ally” and his anarchist band, and ruthlessly eliminated them. Makhno escaped but died of tuberculosis while in exile, forgotten and in dire poverty, presumably an enemy of the people.

Are there historical lessons to be learned here? Yes, for example: (1) The dreamy-eyed, extreme right-wing anarchists have never been a match for the conspiratorial communists and socialists of the left; (2) Totalitarianism and collectivism are evil philosophies derived from the incitement of the dark side of human nature; (3) Since men are no angels, some government is needed to restrain them; and (4) History teaches us that as far as the creative mind of men is concerned, a Constitutional Republic, a limited government of laws and not of men, is the best form of government ever created. Injustice does not rule forever, and so in 1989 the Berlin Wall came tumbling down and in 1991 the evil Soviet empire collapsed of its own totalitarian and collectivist weight. Finally, we must remember the words of British statesman, Edmund Burke (1729-1797), one of the founders of modern conservatism, who said, “When bad men contrive, the good must associate; else they will fall one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle.”

Addendum — the Anarchists’ Brief Existence in Cuba during the Machado Government

Anarchism came from Spain. In Cuba during the presidency of General Mario García Menocal, 3rd President of Cuba (1913-1921) (Conservative Party), the anarchists had been essentially coopted by the Menocal government and communists were non-existent, until the impetus of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Nevertheless with the wealth of Cuba and the good times with the “Dance of the Millions,” there were no major complaints from these insignificant groups. The political fight was between Liberals and Conservatives, and how they stood with the Platt Amendment. The Menocalistas had put down an insurrection of the Liberals led by Cuba’s Second easy-going but corrupt Liberal President General Juan Miguel Gómez in1917. Meantime, the two extreme radical factions were growing, while collaborating with each other, they also competed to attract workers and infiltrate the unions.

The situation changed with the ascendancy and turbulence of the presidency of Liberal dictator Gerardo Machado (1925-1933), the Confederacíon Nacional del Trabajo (CNOC), a workers union formed in 1910, had become more influential with greater numbers and the competition between the two groups intensified. The leadership of the CNOC had been led by anarchists, who unlike their counterparts in Spain, were less militant. The more radical socialists and communists fought for control in 1931 had overthrown the anarchists and gained control of the CNOC. The radical anarchist leader Carlos Baliños even left the movement and joined the socialists and eventually the communists. As the street violence and terrorism increased against the ruthless dictatorship of Machado, government officials were assassinated and the anarchists hunted down. And as would happen later in Spain, the communists began to kill the CNOC who were not communists. Anarchists were exterminated or even betrayed to Machado’s police, who also murdered them.(5) Those lucky to survive left Cuba for Spain where a revolution in 1931 had brought about a republic. As we have noted, in Spain they would be exterminated by the Soviet NKVD during that same decade.

Read Part I of this series.

References and Notes

1) Read my review of the case at:

In this same review I also discuss Stalin’s robbery of Spanish gold, as Russian troops commanded by General Alexander Orlov were ordered to do so by Stalin while, at the same time, pulling the rug out from under their Republican Spanish allies. See also Alexander Orlov: The FBI’s KGB General by Edward Gazur (2001) and Deadly Illusions: The KGB Orlov Dossier Reveals Stalin’s Master Spy by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev (1993). The reader is also advised to peruse KGB General Pavel Sudoplatov’s book, Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — A Soviet Spymaster (1994). Another excellent source on the NKVD liquidation of anarchists and Trotskyites during the Spanish Civil War is The Sword and the Shield — The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999).

2) An excellent source not just on anarchism but on revolutionaries of all political persuasions is Martin van Creveld’s The Encyclopedia of Revolutions and Revolutionaries — From Anarchism to Zhou Enlai (1996). This book is absolutely essential for the study of revolutions and revolutionaries.

3) Harrison E. Salisbury’s Black Night, White Snow (1977) is an idealized history of the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917. The book is beautifully written by a veteran journalist but unfortunately tilted with enchanting admiration to the reigning intelligentsia and the Russian radical revolutionaries, not those who toppled the Czar in the February Revolution, but only those who took the spoils later in the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks. The author is so mesmerizing in his enchanting narrative prose and flair for turning elegant phrases that we tend to forgive and forget his overt liberal bias exuding from the pages of his otherwise magnificent book.

4. Fyodor Dostoevsky spent four years in a forced-labor, prison camp in Siberia, following his conviction for involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle. Those were very difficult years but, ironically, his subsequent years in exile in Siberia were much better. Therefore, one must not confuse Russia’s tsarist legacy of autocracy and authoritarianism with Soviet-style communism and totalitarianism. In fact, Dostoyevsky could not muster approval from the Tsar’s (or Czar’s) censors for some of his writings because his description of life in exile was deemed too comfortable and would invite criminals to commit crimes to get there! Compare that to the much worse, Soviet gulag system! Imagine the irony when Dostoyevsky had to edit his manuscript (magnify his discomfort in exile) in order to pass the censors and get published in Tsarist Russia! (House of the Dead, (1860-62), semi-autobiographical novel)

5) For the history of the anarchists in Cuba, see Hugh Thomas, Cuba, or the Pursuit of Freedom (1998), p. 586-597

Written by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria, Jr. is a former Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine; Former member Editorial Board of Surgical Neurology (2004-2010); Member Editorial Board of Surgical Neurology International (2011-present); Recipient of the Americanism Medal from the Nathaniel Macon Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) 1998; Ex member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002-05; Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002); Editor Emeritus, the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS); Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002).

An edited version of this article was published on October 27, 2011 at GOPUSA.com.

Copyright ©2011, 2018, Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD

4 thoughts on “The Political Spectrum (Part III) — The Extreme Right: Anarchism”

Fascinating history between the two groups. So often we see the two together with Antifa, hammer and sickle flying on flags with anarchists symbols alike. So it is puzzling that anarchists who want no authority would ally themselves with Communists who seek total power. I suspect that Communists likely see these “useful revolutionaries” as helpful in the destruction faze of the revolution to be quickly disposed of when convenient, while the Anarchists see an ally in destruction of order.

However, it occurs to me that the Bolsheviks and Anarchists have more in common than I used to think. Both seek a “state-less society,” and both seek destruction of society. Marx saw a “stateless society” that would come after feudalism>capitalism>socialism>Communism>stateless society when “armed people” (Lenin) of proletariats would keep order.

Naturally, Communism aims for what the party would never accept nor have ever achieved: a stateless society. For Dictators rarely relinquish power when given a different option, despite the Marxist belief that economics changed the man from the outside inward. The clear difference does stand out that the Marxist/Communists must first attain totalitarianism before the no government utopia—from all power to no power. Anarchists do not need this totalitarianism; moreover, that would be the opposite of what they seek. Perhaps they do not look beyond the immediate joy of destruction.

Anarchists and Communists both demand destruction. Communists demand the destruction of the family, religion, government, private property rights, former allies, and essentially any impediment to the all-powerful state, under the one-party Communist Party of course. Anarchists seek this destruction as well, although I do not think they believe in the Communist magical utopia that will emerge. I suspect they may just enjoy anarchy.

It has always seemed to me that Anarchists were used and tolerated by the Communists simply because of their usefulness. Once the Bolsheviks consolidated power enough they began their persecution and elimination of Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, and Anarchists by 1918. They sought elimination of the leaders and consolidation within the ranks of radicals, revolutionaries, and socialists—some of whom sought peaceful socialism—before going after the larger, common enemy, the Whites. Totalitarianism demands all allies must submit to the one party rule or be eliminated.

Hi Koba, the “stateless society” for the communists is a useful myth with no bases in fact — pure mendacity for the consumption of the restless masses. They know that it will not happen but it keeps followers as well as future victims in hopeful felicity. Marx as a pure theorist may have believed in this, but not Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and Fidel. Moreover, Marx had no experience with real workers or laborers, only dreamy intellectuals and abstract masses, and had no conception of the yearnings of real working people. The Proof is in the USSR, China, Cambodia, Cuba, North Korea, etc. No stateless society was ever created or even attempted. Totalitarianism is the real goal with collectivism and the ultimate use of force to keep the individual subservient to the State. Individualism is eliminated along with individual rights.

Gullible anarchists, on the other hand, do believe in stateless utopias and workers’ paradises, and collaborate with the savvy communists for the ultimate destruction of the “bourgeoisie state,” so that their egalitarian, individualist society can be created. Some pirates during the 1690-1720, the 30 year “golden age” of piracy, created the most lasting anarchism aboard their ships! As for the terrestrial rest, I discussed them in my article: They were evanescent fantasies devoured by the triumphant, realistic communists. One can say the anarchist served as useful idiots that uniformly ended with violent and brutal ends in the hand of the communists after they served their purposes. Even the violent social revolutionaries, as you know, were devoured by the Bolsheviks. After they were in power, even tigers like Boris Savinkov, were enticed back into Russia by the Cheka via operation Trust and eliminated savagely. I agree with your observations.

Your analysis of a “stateless society” as a “useful myth” precisely confirms both history and human nature. I agree that Anarchists are used as long as they perform a necessary function and discarded once they become inconvenient, just as they were in 1918. I have learned much from your articles, and now that I have found your site again, I look forward to perusing the articles.

It is a real shame that so many of the young people–including those within the Antifa and BLM ranks–are so ignorant of the history of communism. For unless one is ignorant or evil, one cannot follow such a god. I wish more young people knew what happens when governments have all power. Your articles are a good source. Perhaps we can get you on TV again. That last interview was a good one. I bet you and Senator Cruz would make a great interview together.

Note: Through Operation Trust, the Cheka eliminated White Russians who made it to exile. For example, they abducted and killed General Miller, and countless other white Russian emigres. They even lured legendary figures like former social revolutionary Boris Savinkov and British agent Sidney Reilly into the Soviet Union, where they were arrested, tortured, and killed! — Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, Gardners Books (2000).

General Kutepov was kidnapped and supposedly died of a heart attack during the kidnapping in Paris in 1930; Lieutenant General Pyotr Wrangel, former commander Caucasus Army South was poisoned in Belgium by a servant a Soviet agent, etc. Pavel Sudoplatov, Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness, a Soviet Spymaster (1994), is an excellent source.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Trust