- Articles

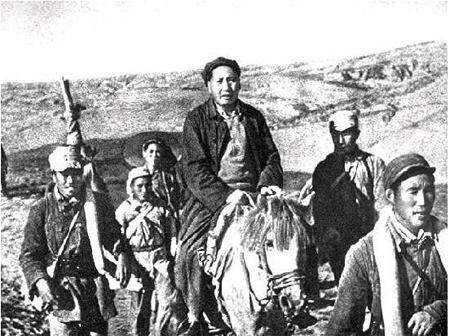

The Mythic Long March of the Red Army Led by Chairman Mao

The author of The Long March: The Untold Story, Harrison E. Salisbury (1908-1993), was an American journalist and an eloquent writer, but he had a romantic, soft spot for young, “idealistic” communist revolutionaries. This infatuation persisted even though these revolutionists ultimately showed their true colors when they attained supreme power, discarded their sense of justice, imposed communism and totalitarianism, and used terror to rule the police states they had created. Instead of the “workers paradise” they promised, Lenin followed by Stalin in the Soviet Union and Mao Tse-tung and his followers in China brought unspeakable horror to the people they claimed they had liberated. Salisbury was a great journalist, nevertheless he was able to wear blinders, super-imposed on rose-tinted glasses when writing about these monsters. This is true for Vladimir I. Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and the rest of the Bolsheviks in Salisbury’s novelistic and best book, Black Nights, White Snow, about the Russian October Revolution of 1917, and even more so with Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese communists during the period 1934-1935 in The Long March: The Untold Story.

Fabulous Storytelling

Despite this infatuation, the book reads well because Salisbury is a fabulous storyteller and his narrative is enthralling and mesmerizing. He admired these men, and in the case of Mao, he glosses over his worst crimes and excuses his excesses attributing them to “his final years.” There is no condemnation of the “Hundred Flowers Campaign” and the “Anti-Rightist Campaign” (1957), the disastrous “Great Leap Forward” (1958-1961) or even the infamous “Cultural Revolution” (1966-1976), suggesting only these were errors (as in breaking eggs to make omelets) or due to Mao’s growing infirmity “in his final years.” To his credit, Salisbury summarizes Mao’s crimes against his former communist companions, the heroes of the Long March, against whom Mao turned with a vengeance during the Cultural Revolution. But there is no outrage to the crimes against the Chinese people and the 70 million victims, who perished at the hands of Mao’s communist government. Despite all the evidence available to Salisbury, The New York Times correspondent, suggests the Chinese people were better off during Mao’s communist dictatorship than under Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists before the communist takeover of China in 1949!

Mao’s Canonization

Advancing the official version of the Long March propagandized by the historians of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), who still venerate Mao and mythologize the heroic details of the Long March, Salisbury completely loses his objectivity, and like Edgar Snow before him, crosses from non-fiction history to revolutionary mythology and fantasy. But as we have said, Salisbury is a master storyteller, and we are taken on an interesting adventure that, unless we repeatedly break the seductive spell, distorts the pages of the true and more ghastly historic record.

It is disingenuous that in the midst of page 71, Salisbury abruptly changes his narration of the “conspiracy of the litters” during the Long March to solemnly inform us: “Only with Mao’s death on September 9, 1976, the arrest and destruction [of the Gang of Four]… is it becoming possible to disentangle the real Mao from the caricature created by the hagiographers.” We expect Salisbury to tell us about the real historic Mao, but he does not. Salisbury goes on for the rest of his narrative to surpass the communist chroniclers of Beijing and the Marxist academicians of the West to create a supreme hagiography of his own, one that eclipses all. Mao, who killed over 70 million of his own people, is canonized as a communist saint, and his mistakes attributed only to “his final years,” when Salisbury suggests that the Chairman might have lost grip of his faculties.

The Fantastic March Retraced

The readers must be cautious not to be seduced by the song of the sirens in the waves of the eloquent prose because Salisbury is, again, a great storyteller, and the unwary may be tempted to believe the fantastic tales and perilously crash in the turbulent waters of a highly embroidered historic account. A more realistic portrait of Mao is canvased in vivid colors in the authoritative tome, Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (2005).

Of interest is the fact Salisbury obtained permission from the PRC’s government, and at age “nearing 75,” successfully retraced the route of the Long March. It is ironic that Salisbury was accompanied not only by his wife but also by the former diplomat, John Stewart Service, an American communist sympathizer and literal “,” who did his utmost in this diplomatic post to assist Mao Tse-tung and the communists to gain power in China in 1949 over Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists.

The Red Army Supermen of the Long March

To Salisbury, Mao is a communist saint and the Red Army men and women of the Long March are the Chinese version of Nietzsche’s ubermensch, enduring and heroic supermen who, purportedly, pay for everything they take from the oppressive landlords. And who are really these “well-to-do” and “rich peasant” landlords, these Chinese “kulaks”? They are for the most part not wealthy but those slightly better off, those who had incited the envy of their neighbors because they have risen above the rest to own more than a couple of acres of land and more than a couple of pigs and chickens! Returning to the heroic Long Marchers, they can march 60 miles a day, despite meager rations and marching in harsh terrain (no roads) in sweltering heat, and they can do this for several days in a row, if ordered by Mao to do so, happily and without complaining.

While there were tactical marches and countermarches, and battles and river crossings, the fact of the matter is that the Long March was strategically a shameful and ignominious long flight of the Red Army to escape from the claws of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army. There were not brilliant, decisive battles in which the Red Army smashed the Nationalists, no military genius of Napoleon, Robert E. Lee, or even Leon Trotsky. The greatest wonder of the Long March was not the arduous, protracted retreat and escape, but the fact that for the most part, despite being corralled and hotly pursued by the Nationalists, the communist leaders including Mao and Chou En-lai continued to plan, intrigue, give orders, and lead — directly from the litters in which they were being carried by the hapless bearers!

Chiang Kai-shek and Joseph Stalin

Additionally, authors Chang and Halliday have made an excellent case that one of the main reasons the heroic Marchers were not totally annihilated, and that was simply because Chiang Kai-shek did not want to alienate the great Stalin, with whom Chiang still had good relations. Stalin had urged cooperation between Mao and Chiang because of the serious Japanese threat on his right flank and the possibility of a two-front war for the USSR, . Stalin, in fact, saved Chiang Kai-shek’s life later in 1936 during the remarkable Xi’an incident when the Generalissimo was kidnapped by a trusted renegade general. In short, as he decimated Mao’s army avoiding its total destruction, so as not to incite Stalin, Chiang was herding the Red Army survivors in the Long March to force them to go and corral them in the desolate province of northern Shaanxi.

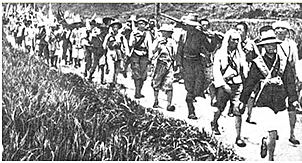

The Long Marchers were on the run, making 40 to 60 miles a day in rough terrain. Circuitous routes, disastrous mistakes, astronomical casualties, desolation in their wake, the Red Army survivors did not make planned, deliberate tactical maneuvers, but plainly outran the Nationalist army. While the mortality among the communist elite being carried in litters was zilch, the common soldiers did not fare as well. They had a mortality of 95%! In Mao’s First Front Army, out of the 86,000 men who began their journey in Mao’s backyard in the southern Soviet province of “Red Jianxi,” only 4,000 men and women survived to reach northern Shaanxi, their final destination. The Fourth Army fared much worse; and it was not decimated, but completely annihilated.

How a disastrous retreating flight and decimation of an army has been turned into a Chinese revolutionary triumph of legendary proportions is the master stroke of Mao and his hagiographers. In short, Salisbury’s The Long March is a literary masterpiece of mythic revolutionary propaganda, but it is not objective history. Read this classic with this serious caveat — and then read Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (2005) for the real and largely unknown history.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.), Mercer University School of Medicine. Dr. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). Dr Faria has written numerous articles on Stalin, communism, and the Soviet Union, all posted at the author’s website: aciendaPublishing.com.

Copyright ©2014 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

The Long March: The Untold Story by Harrison E. Salisbury. The Franklin Library (Signed First Edition Society), Franklin Center, PA, 1985, 419 pages.

The photographs used to illustrate this commentary came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Salisbury’s The Long March: The Untold Story.

1 thought on “The Mythic Long March of the Red Army Led by Chairman Mao”

This is as one of the most famous and instructive journalist of his day saw Mao and his mythic long march!