- Articles

The Economic Terror of the French Revolution

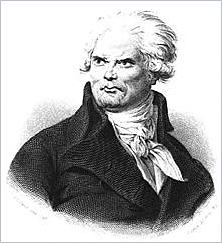

Maximilien Robespierre and his fellow Jacobins never came close to attaining the utopian goal of establishing a “Republic of Virtue.” In fact, they did not even come close to establishing the rule of law essential to a constitutional republic. Natural rights to life, liberty and property, which are protected in our American republic, were not respected by the French revolutionists. Forced fraternity and equality proved to be (and remain) mutually exclusive of individual liberty. What the French Revolution established was mob rule followed by the bloody dictatorship of Robespierre and his Committee of Public Safety (July 13, 1793 — July 27, 1794).

The French Revolution also showed the world the scissors strategy of class struggle and warfare at work. This methodology forced rapidly and inexorably radical change upon society. The engine of this struggle was fear and, ultimately, terror. In the next century, Karl Marx elaborated and expounded on that destructive methodology, borrowing from Hegel’s dialectic idealism that relied more abstractly on historic analysis and cultural conflicts. Unlike Hegel’s, Marx’s system of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, appealed to the darkest side of human nature, envy and hatred. His system constituted the class struggle of dialectical materialism that would result, as history unfolded, in communism. This philosophy of evil, Marxism, would cost upwards of 100 million people their lives in the blood-tainted 20th century.

And yet, for all its horror, the French Revolution had little success implementing economic equality. The politics of terror proposed by the most militant of the French Revolutionists in the end consumed them while failing in its underlying objective of forcing wealth redistribution. Neither fraternity, liberty, nor economic equality was achieved. Instead of an earthly paradise, an infernal state of anarcho-tyranny ensued and a Reign of Terror was created.

Between 1792-1793, while the State did confiscate property of “enemies of the revolution,” Maximilien Robespierre and his Jacobins kept such property that was salvaged from the mob in the hands of the government, and the rank and file revolutionists were required to keep an inventory of the appropriated goods, estates, and landed property. Stealing goods that belonged to the State could result in a quick trip to the guillotine. Looting and plundering, nevertheless, took place as a result of the prevailing state of anarcho-tyranny, but it was limited to a fraction of what it could have been, given the savagery and ferocity displayed in the riots by the revolutionary mobs. In a way, this firm, strict accounting of expropriated property was helpful in keeping the mob from looting and overrunning France.

While Robespierre glorified organized political riots (particularly those he personally instigated), he disdained spontaneous food riots, unless they could be guided toward worthwhile political ends with which he approved. Robespierre disdained material wealth. From his reading of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he “knew” that material wealth corrupted the noble state of man by which he had been endowed by Nature. Poverty, to Robespierre, then, was synonymous with Virtue.

François Babeuf, a journalist and political activist, was one, if not the first, of the modern communist. He espoused radical collectivism in the form of immediate land redistribution and economic equality, but his ideas never took hold with the leading Jacobins.* And yet, according to David P. Jordan, who wrote a virtual apologia of Maximilien Robespierre, the Incorruptible, both Saint-Just and Robespierre believed the State had a role to play in providing for “minimal subsistence” to the people.(1) This was “the debt of the rich to the people.” A.J. Buissart, an old friend of Robespierre from Arras, agreed. He wrote Augustin Robespierre (Maximilien’s brother) that the people “were dying of hunger in the midst of abundance. I believe it is necessary to kill the mercantile aristocracy just as we killed that of the priests and nobles.” Robespierre never went as far as calling for the death of the bourgeoisie, although he threatened and admonished them, “the rich egoist may share the fate of the nobles and the King if they continue to behave like them.” Although Jordan claimed that Robespierre only threatened but did not move against the mercantile class, the truth shows that the Incorruptible was beginning to move in that direction. Only political considerations and timing prevented him from eventually unleashing his wrath against the enriched bourgeoisie. Robespierre’s modus operandi was to carefully pick his enemies, one at a time, and only at the appropriate moment summarily destroy them.

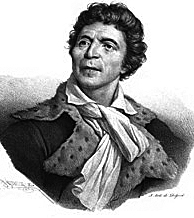

In the spring and summer of 1793, the National Convention began to move against the mercantile class. It was already under pressure from the militant leaders of the Commune and the Paris sections, René Hébert, Pierre Chaumette, and François Hanriot, who were then flexing their muscles by mobilizing the mob and parading them in front of the Convention. Hébert was a rabid journalist and editor of the Le Père Duchesne newspaper; Chaumette was a radical leader of the Paris Commune; and Hanriot was the bloodthirsty head of the National Guard. There were also the self-appointed friends of the poor, the ex-vicar Jacques Roux and the well-to-do young extremist, Jean Varlet. The latter two were formidable rabble-rousers who preached the gospel of economic equality. They were referred to as the enragés for their tirades against the new established order of the National Convention led by the Jacobins. For them, the revolution still had not gone far enough on the road to complete social and economic egalitarianism. Their demagoguery was even irritating to Robespierre and his ruling Jacobins, who, now in power, believed the revolution stopped with them.

At one point, Pierre Chaumette, leader of the Paris Commune, with a mob behind him, demanded that the National Convention immediately authorize the government to confiscate private property and distribute it to the “people.” He had the support of Hanriot and Jean Pache, the mayor of Paris. However, by this time, the ruling Jacobins in the National Convention had learned how to manipulate the sans-culottes and the armées révolutionnaires, andthese demands went unheeded, much to the chagrin of René Hébert and his ultra-radical friends and followers.

Nevertheless, in an effort to ease the worsening economic situation and placate the enragés, the Convention was forced to consider implementation of wage and price controls, as well as strict regulation of the grain market. It also considered imposing a ceiling on the price of grain and other assorted, everyday grocery items, like bread and cereals. The Girondin leader, Charles Barbaroux, already a marked man by the ferocious Jean-Paul Marat, who was then at the peak of his power, and the Hébertistes, nevertheless, spoke in opposition. Barbaroux explained that the price ceiling would exacerbate the problem of supply and demand and aggravate the scarcities. Pierre Vergniaud, the golden-tongued Girondin orator, and Georges Danton, the most popular of the Revolutionists, also opposed these extreme economic measures.(2)

On March 13, 1793, Vergniaud, at great peril to his life and that of his fellow Girondins, rose to denounce the people’s demagogues. He spoke against the unconstrained lawlessness of the Parisian mobs, as “idlers, men without work, unknown, often indeed strangers to the section or even to the city itself ignoramuses, great putters of motions in love with the sound of their own voice, men easily corrupted for bad causes.” As for the cries of equality, these demagogues reminded him of the “tyrant of antiquity [Procrustes] on whose iron bed victims were mutilated if they were too long for its measurements.” Despite the threats from the radicals on the floor of the Convention he continued his oration, “This tyrant also loved equality and voilà, that is the equality of the scoundrels that would tear you apart with their fury.”(2)

That summer, the Convention also went ahead and implemented price ceilings, maximum wages, relief for the poor via obligatory loans, and levied exorbitant taxes on the rich. Businesses were forced to accept depreciated fiat currency, assignats. All of Barbaroux’s predictions came to pass, including the inflation he posited would take place because of the drastic wage and price controls, the devaluation of the currency, and the overall, loose fiscal policy.

But these policies were not enough to placate the demagogues of the left and their supporters. On June 3, 1793, twenty-two Girondin Deputies, including those who had consistently defended civil liberties and who had led the opposition against the extreme economic measures, were summarily expulsed from the Convention and arrested, as demanded by Jean-Paul Marat, Hébert, and the mob.** As if this was not enough for the enragés, Jacques Roux addressed the Convention on June 25, 1793 and accused the new “commercial aristocracy” of being “more terrible than the [old] nobility.” He called for the crushing of the rich and of those who had financially benefited from the Revolution.

On July 26, 1793, the death penalty was instituted for hoarders of grain and other “blood-suckers,” including currency speculators. The economic Terror was now well underway. The armées révolutionnaires were empowered to search around the towns and countryside, ransacking houses, barns and warehouses, looking for stored grain. Accused hoarders and speculators went to the guillotine, if not summarily torn apart by the revolutionary mobs. In the rural villages and communities, the sans-culottes and the revolutionary armies left desolation in their wake. Not surprisingly, the economic situation continued to worsen steadily and the monetary policy collapsed. The depreciated assignats were finally demonetized with the creation of another black market, that of hard currency.

By the fall of 1793, the economic Terror was catching up with the political and social Terrors. By the first week of November, after a show trial, twenty-two brave Girondin Deputies and their sympathizers had been guillotined. By November 23, the Jacobins, in full control of the Convention, moved against the moderates, the Feuillants, and their leaders Charles Lameth, Adrien Duport, and Antoine Barnave, referred to as the “triumvirs,” were likewise executed. At the turn of the new year, Robespierre directed his attention to his pesky left and René Hébert and his ultra-radicals were picked up and tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal. Hébert went to the guillotine on March 24, 1794.***

The economic and financial misdeeds of some of Georges Danton’s closest friends, such as the aspiring author, Fabre D’ Eglantine and the not-so-close associate, ex-Capuchin, François Chabot, in part, predicated the fall of the Titan of the Revolution. Finally, Robespierre had found Danton’s Achilles heel — i.e., alleged financial misdeeds, if not by him, his friends, referred to as the Indulgents. Thus, Robespierre used guilt by association to trap Danton and mark him and his friends (who at this point represented the political “right”) for destruction. The Incorruptible also demonized his former friend and colleague, calling Danton a “rotten idol.” Danton fought like a caged lion at his trial but to no avail. The verdict had already been predetermined by Robespierre. Danton and his friends rode on the revolutionary tumbrils down Rue Saint-Honoré to the guillotine on April 5, 1794.

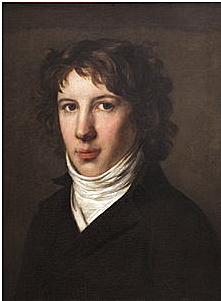

The Ventôse decrees (February 26, March 3, 1794) proposed by Robespierre’s most trusted lieutenant, Saint-Just, provided that the State should confiscate émigré property and distribute it to the needy. Saint-Just and other Jacobins argued that accused enemies of the revolution had no civil rights and their property should be confiscated. Robespierre, although supportive of these decrees, never felt he had the support of even the most hard-line Jacobins to implement them. Private property was still sacrosanct to mainstream Jacobins so the decrees died without enactment. Other forms of the economic terror, however, remained in place. In fact, the country, particularly Paris, now seemed paralyzed with fear as terror had become the order of the day.

On July 4, 1794, Bertrand Barère, a centrist member of the Committee of Public Safety, tried to reach a compromise with Robespierre’s right-hand men on the Committee, Saint-Just and Georges Couthon. The revolution was now in the midst of its bloodiest phase, the Great Terror. Barère proposed to them that he would steer the Ventôse decrees through the legislature, if Robespierre would only stop hunting Deputies and end his quest for virtue. After all, those legislators who were still representative members of the Convention were all fellow Jacobins (i.e., except for the cowed and centrist Plain, which by now voted in full acquiescence with the Jacobins). Barère would help implement further economic reforms in exchange for Robespierre ending his persecution of the less pure Jacobins. But, Robespierre refused to compromise. Establishment of the Republic of Virtue was not on the table for discussion. In his speech of 8 Thermidor (July 26), he explained that he would continue to exterminate wayward Deputies and other enemies of the revolution and would achieve that ultimate goal, the establishment of his Republic of Virtue inspired by his cult of the Supreme Being.

Robespierre never attained that goal. On 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794), he fell from power, and along with seventeen of his malevolent, sanguinary followers, including Saint-Just, Couthon and Hanriot, went to the guillotine where he, to quote another one of Hébert’s morbid terms, “sneezed into the sack.”

The Reign of Terror ended with the fall of Maximilien Robespierre.(3) In the wake of the Thermidorean reaction that followed, the French revolutionists, and later the ruling Directory, instituted laissez faire capitalism. The government welcomed new business enterprises from 1794-1799, but, unfortunately, the social and political situation remained unstable and not conducive to national prosperity.(4) In the end, the government of the Directory came to a revolutiuonary anticlimax with the coup of 18th Brumaire and the ascendancy of Napoleon Bonaparte. With Bonapartist rule, social, political and economic egalitarianism was over, even though the newly installed benevolent dictatorship still proclaimed, at least in slogan form, liberté, fraternité, and egalité. Rather than a liberalized economy, Napoleon would establish a controlled economy geared for war.

Footnotes

* François Babeuf (1760-1797) founded his journal in 1794 and the Conspiracy of Equals in 1795 to overthrow the ruling Directory and establish virtual communism in France. In 1797, he was arrested, tried, and executed for leading a plot to overthrow the government.

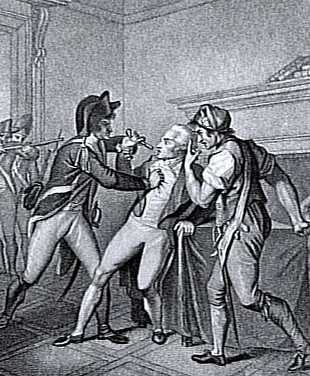

** Barbaroux escaped to Caen where he made a fateful acquaintance with Charlotte Corday, the Girondin sympathizer, future heroine and assassin of bloodthirsty Marat (July 13, 1793).

*** In January, Roux stabbed himself to death to avoid the blade. Hébert dishonored himself in front of the crowds he had so often incited to violence showing hysterical cowardice “as he looked out of the Republican window,” one of his morbid terms for the guillotine. Chaumette and Pache followed and also died by the guillotine that spring 1794.

References

1. Jordan DP. The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre. New York, NY, Free Press, 1985, p. 150-164.

2. Schama S. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, NY, Alfred A. Knopf, 1989, p. 714-716. See also p. 678-847.

3. Scott O. Robespierre, The Fool as Revolutionary: Inside the French Revolution. Windsor, NY, The Reformer Library, 1974; and Loomis S. Paris in the Terror. New York, NY, Dorset Press, 1964. The dramatic events surrounding the reign of terror and the fall of Robespierre are vividly described in both of these excellent books.

4. Hibbert C. The Days of the French Revolution. New York, NY, Quill-William Morrow, 1981, p. 271-304.

Note

This article was first published in Hacienda Publishing in 2003, but we are republishing it because it draws certain parallels with what is happening today with the country upside down with COVID and the disastrous foreign and socialistic domestic policies attempted by the Democrat Party in charge of the Presidency and Congress of the U.S. in 2021.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, M.D., is Associate Editor in Chief in neuropsychiatry; history of medicine; and socioeconomics, politics, and world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI). He was appointed and served at the behest of President George W. Bush as member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2002-2005. Dr. Faria is a Board Certified Neurological Surgeon (American Association of Neurological Surgeons; retired); Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is the author of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His recently released book is America, Guns, and Freedom: A Journey Into Politics and the Public Health & Gun Control Movements (2019).

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. The Economic Terror of the French Revolution. HaciendaPublishing.com, August 26, 2021. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-economic-terror-of-the-french-revolution/.

Copyright©2003-2021 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.