- Articles

The Assassination of Marat, the Girondins, and the Terror by Miguel A. Faria, MD

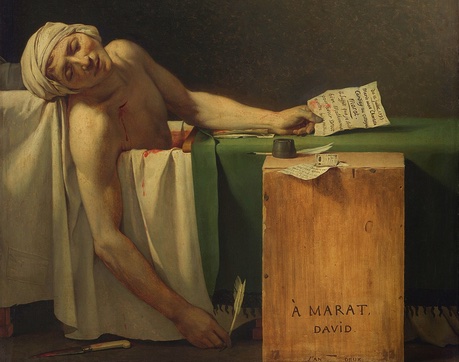

On July 13, 1793, a young woman and a Girondin sympathizer, Charlotte Corday, walked bravely into 30 Rue des Cordeliers and assassinated the radical and bloodthirsty Jean-Paul Marat. The radical journalist and deputy had forced the expulsion of the Girondin leaders from the National Convention and was finalizing his plans for their subsequent trip to the guillotine when Corday cut his life short by stabbing him to death as he soaked in his bath. To alleviate discomfort due to a terrible skin condition, which physicians had diagnosed as “scrofula,” Marat often soaked for long periods of time in his “hip bath—a portable, copper-lined contraption shaped like an old-fashioned high-buttoned shoe”—as he worked on revolutionary business and the publication of his newspaper, L’Ami du Peuple.

Around noon on that fateful day, Corday penned an intriguing note to Marat, and had it delivered to his residence. In it, Corday stated that she had come from Caen and added “your love of your country should make you curious to know the plots which are afoot there.” Receiving no reply, she sent another note later the same afternoon inquiring, “Might I hope for a moment’s interview with you?”

When she failed to receive a reply to her second letter, Corday presented herself at Marat’s apartment around seven thirty in the evening. She was able to gain entrance since “the newspaper was being prepared for distribution on the following morning” and there was much activity in the residence. Author Stanley Loomis explained what transpired next:

Marat’s astonishment must surely have equaled hers. No woman such as this had ever entered his apartment…Motioning towards a stool…beside his bathtub, he enquired what he might do for her. [Corday] said she had come from Caen and had interesting information to give him about the uprising there. He asked her questions and as she answered he wrote. He asked her for names…and she listed the names of the Girondins at Caen: Gaudet, Barbaroux, Pétion, Buzot…. When she had finished, he laid down his pen and with a grin said to her, ‘Excellent! In a few days’ time I shall have them all guillotined in Paris.

With those words, Charlotte Corday drew the knife she had concealed and “with full force drove it into Marat’s chest.” The blow barely missed the ribs and “cut directly through a lung and penetrated the aorta.”

Even as the shocking news of Marat’s assassination spread through Paris, Charlotte Corday, age 24, remained calm. She faced her trial valiantly. The prosecutors attempted to prove her actions had been part of a wider Girondin plot to murder Marat. The suggestion was of course ludicrous, and Corday denied it emphatically. Nevertheless, the Revolutionary Tribunal found her guilty. On July 17, 1793, just four days after Marat’s death, she went to the guillotine bravely at the Place de la Révolution.

The Jacobins realized that Marat dead would be “more useful to them than the unpredictable, choleric live politician.” Thus, his “sacralization” became an article of revolutionary faith and a “powerful tool of revolutionary propaganda.” Marat was turned into a revolutionary martyr, and immortalized in the idealized painting, The Death of Marat, by Jacques-Louis David. His funeral was a massive spectacle also orchestrated by David on behalf of the government. And in 1794, Marat’s coffin was moved to the Panthéon (“the temple of the gods”)—a monument that King Louis XV of France began as a church honoring Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris. He was interred near Voltaire and replaced Mirabeau. The remains of Mirabeau had been removed by order of the National Convention when secret papers confirmed that the statesman had worked clandestinely to protect the monarchy.

The Girondins Pay The Price For Attempting to Restrain Revolutionary Violence

The assassination of Jean-Paul Marat accelerated the demise of the Girondin deputies, who represented the provinces and had opposed the radicalism of the revolution and the Parisian violence. Twenty-two Girondins had been removed from the Convention and placed under house arrest.

Marat’s demise also fueled the fire of the already gathering conflagration—and ignited the Reign of Terror. It provided the excuse Robespierre and the Jacobins needed for the inception or rather the acceleration of the Terror. Moreover, the Committee of Public Safety “rapidly turned itself into the most concentrated state machine France had ever experienced.”

Although the Girondins were revolutionaries, by contrast they were the more reasonable politicians and statesmen, representing some of the independent provinces of France. Their districts opposed the bloodshed, and the radical turn the revolution had taken and resented the concentration of power in Paris. The Girondins were led by the journalist Pierre Brissot (1754–October 31, 1793), the orator Pierre Vergniaud (1753–October 31, 1793), the irrepressible Marie-Jeanne “Manon” Roland de la Platière (1754–November 8, 1793), and her husband Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière (1734–November 10, 1793).

For the most part, the Girondins were patriots and idealists—not conniving politicians or sanguinary revolutionaries who wanted to save the revolution by ending the violence. As a party, the Gironde were frequently divided on issues, and for a time remained oblivious to the mortal threat posed by Marat and Robespierre and their radical Jacobin confreres, especially from the late 1792 to early months of 1793. They failed to recognize the need, or rather the necessity, to forge political alliances with other moderate factions or even to befriend the increasingly estranged Georges Danton. Together Danton and the Girondins could have “presented a formidable front to the ambitions of Robespierre,” but not separately. Danton realized this fact, but Madame Roland did not. She just could not forgive Danton for his involvement in the brutal September Massacres of 1792.

In April, the Gironde Party position in the Convention collapsed after their friend and former Minister of War in the Girondin cabinet, Army general Charles-François Dumouriez, defected to the Austrians. All factions soon joined in the attack on the Girondins. Their “calumny appeared as a pamphlet called L’Histoire des Brissotins.” In that slanderous piece of yellow journalism, the Girondins were accused of such actions as “intriguing with the English and the Duc d’Orléans.” Supposedly, the information was “based on papers seized at the Roland’s flat.”

In the autumn of 1793, the executions of the Girondins began. On October 31, the first group of twenty-one Girondins were taken in open-cart tumbrels to the Place de la Révolution off Rue St. Honoré and executed. The group included Pierre Vergniaud and Jacques-Pierre Brissot. The lawyer and orator Vergniaud, a Girondin deputy from Bordeaux, “had thrown away the poison with which he had been provided the night before so that he could die with his friends.” Prior to execution, he rendered his verdict on the revolution, quoting from Roman mythology that he knew so well, and declared: “The revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its children.”

On November 3, the French playwright, Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793), authoress of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, was guillotined.

On November 8, Madame Roland, who had foolishly remained in Paris, was sent to the guillotine. On her way, she asked Charles-Henri Sanson (1767–1840), the public executioner, if she could go first in her group. He told her it was against the rules. But when she turned to him and demurely entreated, “Surely, you would not refuse a lady’s last request,” he complied. She went bravely to the guillotine. As she was being strapped to the plank, she uttered her final words, “Oh Liberty, what crimes are committed in your name.”

After learning of his wife’s death, Jean-Marie Roland, who had been on the run, wrote the following note: “From the moment I learned that they had murdered my wife, I would no longer remain in a world stained with enemies.” On the evening of November 10, 1793, Roland left his refuge in Rouen, sat up against a tree, placed the note on his chest, and ran his cane-sword through his chest.

For Louis de Saint-Just, Robespierre’s alter ego, and other ultra-radical Jacobins, particularly the Hébertists, the executions were not going far enough. On October 10, 1793, Saint-Just declared that not only traitors but also the “indifferent”—those who did not have enough fervor for the Revolution—should be executed. The Terror spread from Paris to the provinces and was in full swing both against the opposition, the indifferent, and the innocent.

Written by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is Associate Editor in Chief world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI) and the author of numerous books. This article is excerpted and updated from Dr. Faria’s 2024 book Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions.

This article may be cited as: Faria, MA. The Assassination of Marat, the Girondins, and the Terror. HaciendaPublishing.com, April 14, 2025. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/the-assassination-of-marat-the-girondins-and-the-terror-by-miguel-a-faria-md/.

Copyright ©2025 HaciendaPublishing.com