- Articles

Stalin, Mao, Communism, and their 21st-Century Aftermath (Part I)—A Commentary by Adam R. Bogart, PhD

Any book by the renowned neurosurgeon, neuroscientist, and historian Dr. Miguel Faria is a pleasure to review. His books come in many varied packages, with just as many varied topics. This book is both a historical review of Stalinist Russia and Mao’s China as well as an update on the present situation in those countries. The book is divided into six parts, each with several chapters. In this review, it will not be possible to touch on all of the subjects Dr. Faria brings up, even those which might seem very important. Some of the original historical material Dr. Faria has researched is certainly of great interest to both the professional historian and the less academically oriented curious reader, but it still remains secondary to the true purpose of this book: To help the reader understand what all this history means to the present geopolitical landscape. In this respect, he has done an excellent job, and this review is written with the same end goal in mind.

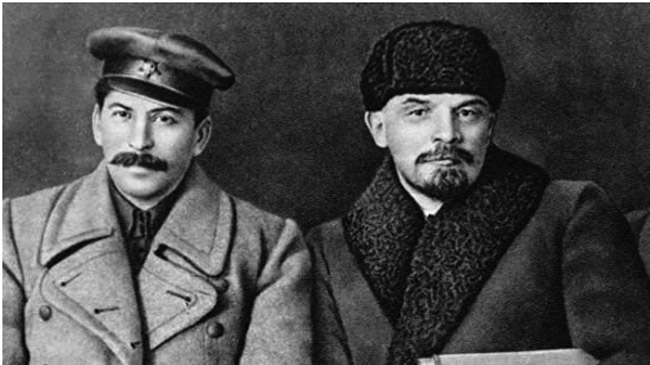

Part I of Dr. Faria’s book, “Joseph Stalin and the Years of Terror” introduces us to Joseph Stalin, whose legacy still endures, and examines the contributing factors which formed Stalin’s personality under his early life, the late Tsarist era, under Lenin, post Lenin, and then through the years 1929–1953 when he had supreme power over the Soviet Union. Most people now know that Lenin was the major enabler of Stalin’s cruelty and his complete disregard for human life. At the same time, Lenin was not Stalin and did not possess Stalin’s pathological paranoid streak. That makes Lenin’s rule from 1918–1924 understandable from a different perspective, although it does not excuse Stalin’s evil control of the USSR or his harsh dictates. Similar to Hitler, one could be a friend of Lenin’s and not part of his dictum that every revolution is maintained by terror. In fact, it is rare to find any evidence of true psychiatric disease (as with Stalin) in any authoritarian or totalitarian. Lenin had severe neurological disease from global cerebral atherosclerosis, and that did have an effect on his ruling style and behavior. However, it had nothing to do with his original goals for the country, or his rise to power. For the most part, Lenin’s mind remained clear. There are suggestions that the cerebrovascular disease did increase Lenin’s level of cruelty, but it probably does not rise to the level of an academic historical matter. The same could be said of Stalin’s own vascular disease later. It is probably true that Stalin became more paranoid due to chronic cerebral hypoxia, but he was already paranoid enough to concoct the Doctor’s Plot in 1948 and consider getting rid of his closest friends and cronies. Where this paranoia originated is unclear but could well be due to the cruelty he experienced at the hands of his father, whose derision and drunken beatings are well known, but I don’t think they were enough. Stalin probably had congenital psychiatric disease that only minimally expressed itself outwardly, but advanced with time, as such disease is wont to do. I think it’s worth noting (especially because it is treated in Dr. Faria’s book) that his mother was no saint either, despite the amount of false religiosity she imbued upon herself. She made little effort to protect her young son from her husband’s drunken fits of anger, and despite Stalin’s fairly good academic performance at the Orthodox Seminary, it is not clear that he appreciated his mother’s desire for him to become a priest. When she visited the Kremlin in 1937, he conducted himself in the pleasant manner one expects of a head of state under such circumstances, but immediately after her death later that year, he was already cursing her, and calling her a “slut.” He sent some flowers, but had Beria go in his place as a pallbearer to her funeral.

Dr. Faria does bring up the similarities between Joseph Stalin and Fidel Castro (and there were many), but the unique position Stalin ultimately occupied was not the same one as Castro occupied. Additionally, Lazar Kaganovich (as brutal as he was) did produce quite a poignant analysis of how Stalin’s character and personality came to be. Kaganovich’s analysis of the stages of Stalin’s development is quite helpful, as are later analyses, such as the writer’s Simon Sebag Montefiore, in his book Young Stalin. However, Dr. Faria’s assertion (in agreement with Montefiore) that “Stalin played a much larger role in the Russian revolution than we have heretofore been led to believe by some historians and documentary filmmakers….” needs a bit of temperance. It was never about Stalin’s objective performance in the Bolshevik revolution (or even the civil war). It was about how others saw it, and as much about how Stalin did. Trotsky was always closest to Lenin during the revolution, and while Stalin took on active roles during the civil war, he could never beat Trotsky as Supreme Commander of the Red Army. Stalin was excellent as a political tactician, but never as a military one. Perhaps associated with his paranoia was self-defeatism and jealousy as fixed character traits.

Nobody really cared about what Stalin and the kind of military roles he took on during the Revolution up to early twenties. It was noticed, of course, but by 1925 there were enough other important issues the country had to deal with when Stalin ruled in the triumvirate of the Soviet Union with Kamenev and Zinoviev. Only someone with such well-developed paranoid traits as Stalin had would still feel that old Bolsheviks knew too much about his role during and after the revolution. In 1925, his power was great enough (though not solo) to render that meaningless. The later purges of 1936-37 were to inspire extreme and chronic fear in the Soviet general population (Lenin’s dictum again—a revolution cannot be maintained without constant terror) but there were some specific reasons and knowing anything about Stalin’s early roles in Tsarist Russia was one of them. As for Trotsky, his exile in January 1928 to Alma Ata and then Turkey, France, Norway, and Mexico rendered him politically powerless, a situation he could not change. He could still write books and pamphlets and give speeches, but was no serious threat to Stalin’s rule. Trotsky should not have made so much noise for nothing, because his August 1940 assassination then became personal for Stalin. Stalin had obtained a copy of “Trotsky’s Testament” (written February 1940), in which Trotsky discusses his thoughts and feelings about how the Revolution had been perverted by Stalin. As Volkognokov puts it, “Stalin had stayed up all night, reading it, and seething with bile.” Volkognokov suggests that this was when Stalin finally decided mere exile would not be enough for Trotsky. The assassin Mercator was recruited for the job, and taught by the NKVD that the best way to induce a quiet death was blunt force to the back of the head. They didn’t want to alert others at Trotsky’s compound, but that is what happened anyway, when Trotsky screamed after he was hit. I know Trotsky could have survived this wound, as x-rays, operative, and autopsy reports make clear. The blow from the ice pick came from the blunt end (adze), so there was a comminuted parietal fracture, but no deep penetration by the sharp ax. The bone fragments from the fracture acted as the only foreign bodies. It didn’t help that neurotrauma specialist Dr. Walter Dandy couldn’t make it in time, and other American neurosurgeons contacted were also immediately unavailable. Trotsky was operated on by one of the first neurosurgeons in Mexico, Dr. Joaquín Mass Patiño. Patiño never excited much academic interest, but he did write a paper in December 1957 describing his method for treating penetrating gunshot wounds to the brain. In this article, Patiño concluded that “the first step when treating any penetrating wound to the head was to treat edema and that trying to stop bleeding from the encephalon was useless because it was always found to be uncontrollable, and the surgical intervention only added surgical shock and anesthetic intoxication.” In the same article, he also stated that perhaps one of the only advantages of early surgical management was to extract pieces of the skull found in the missile’s trajectory because they could become foci for infection. I think that tells us what he neglected to do for Trotsky, who had bleeding and bone fragments extending from the second parietal convolution down to the right lateral ventricle, which was flooded with blood. The massive bleeding is telling, but if Patiño operated to remove skull fragments, the ability of such fragments to become nidi of infection is currently in doubt.

Chapter 2, A Literary Overview of Stalin’s Meat Grinder, Chapter 3, Stalin’s Meat Grinder—A Panoramic View of the Human Devastation, Chapter 4 The Executioners—Nikolai Yezhov and Lavrenti Beria, and Chapter 5, Stalin and Notable Events in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) are all set in the post 1929 era, when Stalin’s power was absolute, and he was still mastering the technique of one-man rule. Here, I take a partial look at these chapters. One-man rule is characteristic of 20th century totalitarianism, but not to the degree that Stalin micromanaged it. Some say Nikita Khrushchev micro-managed the Soviet Union even more, but I disagree because he might have done so with specific attributes (apartment buildings, for example) but not in the more general way Stalin did. Here again, one might assume his pathological paranoia was the root cause of this.

Dr. Faria writes:

As head of the Institute of Military History of the USSR and General of the Soviet Army, Dmitri Volkogonov had access to secret Soviet documents that were not available to other historians up to the time of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika. Volkogonov’s Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy is authoritative, engaging, and an instructive biography of Joseph Stalin, the Red Tsar of Soviet communism. It was published in Russia in 1988 but was not translated into English and published in the West until 1991—the pivotal year when the Russian bear stumbled, bringing about the total collapse of Soviet communism. The fact that Volkogonov’s biography of Stalin was completed and published during the years of glasnost and perestroika is crucial in understanding his work. One gets the impression that he had ambivalent feelings about the ideals, utility, and worthiness of Soviet communism, which he usually referred to as socialism. His ambivalence may have been the result of political doubts and anxiety from his dual life in the communist Soviet Union and then in a democratic Russia in transition. Even by 1988, he had not quite shed the skin of his “socialist” background. To all outward appearances, Volkogonov was a hardline military man, a general, and deputy chief of the main political section of the Soviet army and navy. Secretly, he was a historian, researching and writing about the life of crime of the Red Tsar, Joseph Stalin. One is left to wonder if Volkogonov would have concluded his assessment differently had the Russian edition been finished in 1992 or 1993, rather than 1988. At times, Volkogonov seemed to imply that if Stalin had not usurped the reins of power and Vladimir Lenin’s course had been followed then Soviet communism in the USSR—as originally traced by Lenin and theoretically enforced after his death by a collective leadership—might have ended in a more democratic socialism, a true Russian socialistic, but always elusive, “workers’ paradise.” At other times, Volkogonov seemed to admit that even with the collective leadership, the course of Russian history might not have made a difference because Lenin, just like Stalin, had called for the pragmatic use of force and terror.”

Of course, Dr. Faria is correct in his assessment of Lenin and Stalin, and of Volkogonov. Neither Lenin nor Stalin ever wanted a democratic state with political participation of the very classes they had pledged to protect and grant complete power to. However, it is not clear why they never did. To be sure, there were many formative instances in Lenin’s and Stalin’s lives that explain their cruel character, but those instances could have directed them towards some other political system that still gave them absolute power but didn’t require (in theory) favoring of the peasants and “workers.” Lenin had disdain bordering on hatred for those classes, which even Stalin did not express outwardly so often. I recall a 1929 speech Stalin gave in which he said, “Comrades, there will be mistakes, but the edifice we are building is so grand, that in the end they won’t matter.” This is the very essence of Marxism; the paradisiac communist state is the ultimate fulfillment of the cruel socialist dictatorship. Marx never said when this was supposed to occur, and neither did any known communist leader. The answer to this is only given in great generalities, so then what are the signs one can look to gauge when communism is approaching? It is safe to say that both Lenin and Stalin probably didn’t feel it would be during their lifetime of sole reign over the Soviet state. Notice how antithetical this is to Christianity, which may be practiced cruelly, but doesn’t have an inherently cruel nature, as does communism. The Christian message is simple. It doesn’t promise an immediate paradise, just as communism doesn’t. Also, in common with communism, it doesn’t give a specific date that paradise (in this case, reunification with God) is to arrive for its adherents. It does say that all one has to do is accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior and do so sincerely. Once that is done, there are certain signs Christians can look for that might predict the return of Christ, but that doesn’t assume such importance when one knows that they are going to their deaths without any further molestation experienced on Earth. Also, Christianity may not be forced on anyone, as the decision to become a Christian must be a completely voluntary act. Modern day atheists and atheist communists of any era laugh at this, because it implies those who don’t accept Christ may be in for an eternally rough time. How could an all-loving god sanction this? They don’t realize that firstly, as our understanding of scripture increases, many think Christ may have meant it literally when he claimed that disbelievers only experience an insensate permanent death. Secondly, in any case, it is still the choice of the individual whether to become a Christian or not. It is not the choice of anybody but the ruling elite as to who becomes a communist. Essentially, entire countries do.

With the above outline gleaned to some extent from Dr. Faria’s writings, one might see how Volkogonov thought as he did. Part of it was undoubtedly due to the timing of his book (1988), which meant it was still written while under Lenin’s system, relaxed though it may have become. Dr. Faria notes this, but I also think Volkogonov understands that Lenin and Stalin were not the same types of people in some regard, and that since Lenin valued the lives of Bolshevik politicians, there would have been no purges involving them. That means almost no show trials because show trials typically ended in the execution of public political figures. A majority of the countless millions of victims who went through Stalin’s meat grinder and never came back were average Soviet citizens, with no public presence. There was no need for show trials, because terror could still reign constant in the general population by relatives and friends who bore some witness to the disappearance of a loved one in the middle of the night after a knock on the door and an arrest. Because the victims were known to be innocent of any of the serious charges, this only increased the terror more. What did it mean to be arrested and innocent? Nobody could grasp that, because under Stalin, the proof of guilt was the arrest. Anybody not arrested was innocent, but they still couldn’t be sure for how long.

Lenin had abolished Tsarist capital punishment in 1918. Little did the innocent know that this actually didn’t mean anything. At the same time that he did this, he gave the Cheka under “Iron Felix” Dzerzhinsky absolute power to arrest, try, and execute whomever they pleased. Execution rate was much higher than anything seen under the Tsars because Iron Felix used the same standard of guilt that Stalin later would – that arrest by itself was the proof of guilt. Yet, Lenin could say truthfully say he wasn’t executing anyone, because Iron Felix autonomously was, independently of the Soviet government.

Dr. Faria goes more in depth about the successors to Iron Felix, such as Yagoda, and Yezhov. The career and death of Dzerzhinsky doesn’t seem to have any particular relevance to Stalinism or its development. He was a lawyer by training, a Pole, and loyal to Stalin. Coronary disease signified by persistent angina pectoris seems to be a sufficient explanation for his death in 1934.

Iron Felix had died of a heart attack on a hot July day in 1926, after a fiery speech to the Central Committee. The question a few have asked (including this reviewer) is why did he die? His chronic heart disease was under good medical control, and there were no prior observations of him that would suggest an impending fatal heart attack. We do know that late in his career, he became remorseful for all the orphans he had created by sentencing his innocent victims to death. He devoted much of his time to place them in orphanages and find stepparents for them. Stalin could not have possibly approved of such weakness and the coddling of the families of enemies of the state, as Stalin considered the children of executed “traitors” and “wreckers.” Could he have possibly poisoned Felix? It would not be the only instance we know of Stalin killing people with poison. I think he resorted to poison when he was either not in a position to order an execution, or the person he wished to execute was a public figure not suitable for show trial. Everybody knew Iron Felix was as pure and dedicated a Bolshevik as one could be. In fact, he was so pure that he was known as a fanatic even in the 1920s. How could Stalin hold a trial for him? He was ruling the Soviet Union jointly in 1926, and although co-leader Nikolai Bukharin was essentially powerless, it still meant he did not have the country under his sole control.

There is also the matter of Felix not being Stalin’s man, but Lenin’s. Stalin’s paranoia was such, that even in the mid to late 1920s, one can already see him not trusting anybody in a high position that he alone did not put there. In fact, by the 1930s, he didn’t even trust people he did grant great power to. To an extent, this is why he had Yagoda and Yezhov shot, although Dr. Faria discusses the more immediate and practical reasons for their deaths.

Dr. Faria provides several details of high-ranking officials are military leaders executed by Stalin for one or another reason. Some indeed were guilty, but almost never as charged. However, as we have known for a long time that the charges were almost never true, it is more instructive to examine the personal and political reasons they convinced Stalin they had to die. I don’t have to bring up all of them in this review, but I wanted to examine the case of Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky in a bit more detail, because his case best illustrates Stalin’s oftentimes more hidden motives.

Examining Stalinism’s early effect on the military Dr. Faria writes, “According to Stalin and the NKVD, Tukhachevsky was a member of the Trostkyite-Bukharinite-Fascist counterrevolutionary conspiracy and, therefore, a traitor to the motherland.” We know now that this is complete nonsense, but we don’t have to look hard for more personal motives, motives that in Stalin’s mind would also threaten his political position. Tukhachevsky commanded the Soviet invasion of Poland during the Polish-Soviet War in 1920. His armies were defeated by Józef Piłsudski outside Warsaw. Tukhachevsky blamed Stalin for this defeat, and Stalin blamed Tukhachevsky. It really didn’t matter if both or neither were at fault. This attack on Stalin’s military prowess had to be avenged, and as has been discussed, by the 1930’s Stalin could easily have come to believe it was a threat to his absolute power. Who might Tukhachevsky still be slandering Stalin’s 1920 performance to? Worse for Tukhachevsky, he was not in good graces with later Red Army commander Kliment Voroshilov – though Voroshilov’s later plans were still markedly influenced by Tukhachevsky’s ideas. His brilliant military plans for coordination of warfare by both plane and tank were not received well by Semyon Budyonny, whose plans for cavalry units fighting with horses were looked upon favorably by Stalin. Calvary units to fight a modern, well equipped, and mechanized army (such as Hitler’s) were absolutely ridiculous. If they had not foreseen Hitler’s eventual invasion of the USSR, they knew it was only a matter of time before some modernized army would do the same. Stalin would have done better to get rid of Budyonny and retain Tukhachevsky, but as was previously noted here, his paranoia was ultimately counterproductive, as paranoia often is. It becomes self-defeatist. Whether he cared or not about human life, the loss of so many good young men battling the axis powers didn’t make the country any better. That, he cared about.

It was still too early for Stalin to execute Tukhachevsky after a show trial, because in the early 1930’s, he still enjoyed too much popularity to successfully convince anyone that Tukhachevsky was influenced by anyone. In 1930, Stalin admitted that he, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and Vyacheslav Molotov were convinced of Tukhachevsky’s innocence. That didn’t mean Stalin would forget about the matter. It only meant he realized it would take some time before Tukhachevsky would be ready for show trial. After his arrest in May 1937 Stalin told Yezhov, “See for yourself, but Tukhachevsky should be forced to tell everything… It’s impossible he acted alone.” Stalin was not a fool. He had to have known seven years would make no difference. Tukhachevsky was still innocent and dedicated to the Soviet Union. A bonus for Stalin is that Yezhov’s torture would give them more names for more show trials.

It is important to realize the way Western democracies viewed the show trials. People living under free governments tended to believe the outrageous charges against defendants in Stalin’s late 1930s show trials were justified and true. Those living in Soviet Russia did not necessarily believe any of that. They knew the charges were completely false, but Stalin didn’t care what they believed, as long as they kept their mouths shut. It didn’t matter to him because the more an average citizen saw innocent people found guilty and executed, the more it would inspire terror. That was the only end goal of the show trials. On the other hand, if Westerners thought the trials and executions were justified, then they could still remain pro-Soviet Union and continue their role of “useful idiots.”

Stalin, Mao, Communism, and their 21st-Century Aftermath in Russia and China (January 2024) by Dr. Miguel A. Faria was published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. You can order the book from Cambridge Scholars Publishing. It is a beautiful hardback book, fully illustrated with over a hundred illustrations, including an insert with glossy color prints. In addition, PAPERBACK copies are now available at the reduced price of £39.99. The author discount of 40% means one can buy copies of the book at £23.99. The author discount code is AUTHOR40 and this discount can now be used by friends, family and colleagues for both editions. This code is to be used by buying directly from the publisher’s website.

Read Part II of this Commentary

Reviewed by Adam Bogart, PhD

Adam Bogart, PhD, is a Behavioral Neuroscientist at the Sanders Brown Center for Aging University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. Behavioral Neuroscience Kent State University Kent, OH. Post-doctoral fellow at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Gruss Magnetic Resonance Research Center Bronx, NY. MS Immunology conjointly Adelphi University/Mount Sinai Medical Center New York City, NY.

This article may be cited as: Bogart, A.R. Stalin, Mao, Communism, and their 21st-Century Aftermath (Part I)—A Commentary by Adam R. Bogart, PhD. HaciendaPublishing.com, June 10, 2024. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/stalin-mao-communism-and-their-21st-century-aftermath-part-ia-commentary-by-adam-r-bogart-phd/.

Copyright ©2024 HaciendaPublishing.com