- Articles

Rewriting the French Revolution — Part II

The Brave Girondins

Unfortunately, in her book, Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution, Leigh Ann Whaley seems to admire the most radical Jacobins and by bringing down the reputation of the brave Girondins, she hopes to bring all the radicals of the French Revolution to the same level. No easy task! And so it was the Girondins’ fault that they were executed. The purged Girondin Deputies had been “intransigent” and had acted “illegally,” rising against the National Convention, as if this violated legislature was acting lawfully and with legitimate authority. It did not. Anarchy and tyranny had become the order of the day in France, and the Jacobin fanatics without the Girondin opposition were now unopposed and free to begin the Reign of Terror.

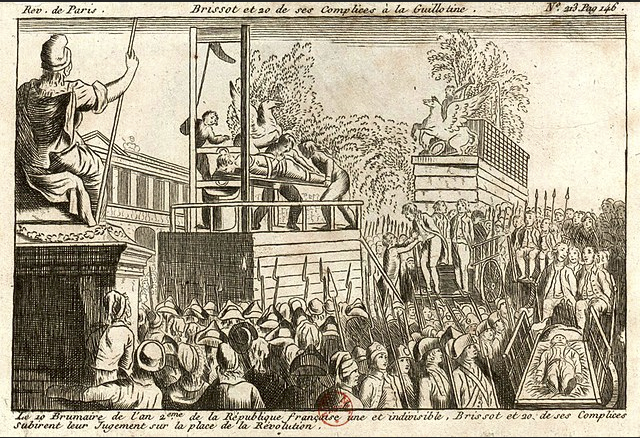

Even if the Girondins had been lawfully executed, as Whaley suggests, for rising against the Convention, what can be said then about the extermination of the aristocrats, the monarchists, the clergy, the Feuillants (constitutional monarchist), and later, Danton himself, the titan of the Revolution, and his friends (the “indulgents”)? Why were all of these citizens and factions serially guillotined?

Eventually, even the very dregs of the revolutionary movement who had risen to the top on the shoulders of the mob would also go to the guillotine: the terrorist René Hébert himself and his friends would “sneeze into the sack.”

By this time as the Terror progressed, Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, supported by their fellow radical Jacobins, reasoned that all of these groups, including their fellow terrorists in the left-wing needed to be exterminated, as to eliminate any remaining political opposition. Thus, a continuous stream of victims kept the bloody, cold steel blade of the guillotine busy. Robespierre’s “Republic of Virtue” was founded on rivers of blood. In Whaley’s rewriting (and her convenient but substantive omissions) of history, it’s as though the Great Terror had not taken place and did not follow the early executions of the Year II!

It appears that this book is an extension of a dissertational thesis attempting to prove that the moderate Girondins (the Brissotins) and the Radical Jacobins (Montagnards) were one and the same, painted with the same broad brush, and separated only by personal rivalries and tactics in the supreme struggle for power. To accomplish this tendentious historical task, Whaley attempts to spread culpability equally among the main characters in the drama and thus establish moral equivalence between the two groups. To this effect, it’s necessary to unjustly rewrite history and demean the valiant but unsuccessful efforts of the Brissotins to get the Revolution back on track and avoid the coming mass murder and terror. Whaley, tactfully but systematically, brings disrepute upon the Girondin leaders and the exterminated leadership of the right-wing of the National Convention, while discreetly acting as an apologist for the ultra-radical Jacobins.

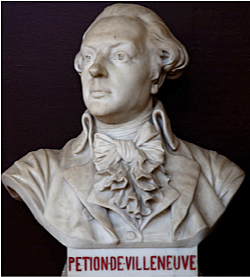

The Girondins admired the ancient Romans and their Republican virtues, and led by Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve had attempted to curtail revolutionary excesses, establish legality and legitimacy to the government, and set the Revolution on a path similar to the United States of America. They did not want the radical Jacobins and their allies, the extremists in the Commune and their supporters in the Parisian mob (the notorious sans-cullotes), to dictate policy for all of France. Indeed, soon after the extermination of the Girondins, the Committee of Public Safety rose to full power and dictated policy based on Terror for all of France.

The Girondins, the champions of the provinces, wanted a referendum to give the people of France a voice, and they sought to save the life of the King without reestablishing the monarchy. Their intention was humanitarian — not only for the King, but for all the people of France in an attempt to prevent the horrible deluge that followed (and predicted by Louis XV). As it turned out, alas, they were unsuccessful and the coming Terror became a hellish reality.

Whaley misses the forest for the trees when she misreads the intentions and aims of the Girondins in such major events as the Flight to Varennes and the September massacres (1792) in which 1200 prisoners were massacred on the order of the radical elements in the Insurrectionary Commune and the Jacobin leadership, most likely including Marat. Victims of the Massacres, a prelude to the Terror, included the Princess de Lamballe, whose head was taken on a pike to the prison where Queen Marie Antoinette, her intimate friend, was being held prior to her own execution.

Some Girondins, including Pierre Brissot and Jean-Marie Roland, intended victims of the September Massacres, escaped this time only to be exterminated later. Billaud-Varenne, an intimate of Robespierre, visited the executioners during the killing and praised them for their work! And what is the authors focus on this event? Not the culpability of the extremists, but the Girondin reaction: Whaley insists that it was only later that the Brissotins denounced the Massacres! The reaction of the Girondin leadership is understandable to anyone familiar with the perilous and anarchic situation in France at the time. Granted, the Brissotins (except perhaps for Madame Manon Philipon Roland), for the first and only time and with good cause, feared for their own lives. Indeed, their existence had been in mortal danger from the time of the formation of the Insurrectionary Commune in Paris (August 9), the Storming of the Tuileries (August 10), Marquis de Lafayette’s defection to the Austrians (August 19) — so that by September 2, when Verdun surrendered to the Prussians, the Girondin’s position was extremely precarious. Denunciation of the Massacres during the brutal period of September 2-6, with their own names on the list of intended victims, would have been foolish and suicidal.

Portrait of Madame Roland by Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, c. 1787

The peculiar behavior of Georges Danton is quite perplexing, and I for once agree with Whaley that Madame Roland’s hostility toward Danton, singling him out and blaming him personally for the September Massacres and other Jacobin excesses, was unwise and misguided. An alliance between Danton and the Girondins even at this late point in the autumn of 1792 could have possibly thwarted the seizure of power by Robespierre and prevented the Reign of Terror; unfortunately for France and the world, it did not happen.

One wonders whether an even earlier alliance between (Comte de) Mirabeau, who died untimely in 1791, Georges Danton, and Marquis de Lafayette might have saved the Revolution, preventing the Terror with the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, as in England, or a truly enlightened, Constitutional Republic, as in these United States of America. Had this happened the world would, perhaps, have been spared the violence and terror marshalled into the 20th century by the Russian Revolution of October 1917 and the ensuing 100 million hapless deaths of world communism.

If the Girondins vacillated at the time of the September Massacres of 1792, it was understandable. Their renewed courage would thereafter not falter and would be proven, again and again, until their complete extermination. With courage, they faced the cold blade of the guillotine or died without submitting to their tormentors. Of the 29 proscribed Brissotin Deputies and friends, only a few, Louvet, Mercier, and Isnard, would survive to tell the tale. There are some interesting parallels between the Girondins in France, the “Kadet” party of Russia during the Russian Revolution, and the 13th of March Movement during the Cuban Revolution, but such comparative discussion is beyond the scope of this review.

In time, the brutal Montagnards themselves would tremble, fearful of the sanguinary revolutionary (terrorist) monster they had unleashed but now could not control. The Reign of Terror would only end with the Thermidorean Reaction and the end of Robespierre and his bloodthirsty Committee of Public Safety. Despite their fate, the Girondins deserve the admiration that history has justly bestowed upon the great tragedy that was the epochal French Revolution.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is editor emeritus of the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons (formerly the Medical Sentinel) and author of “Vandals at the Gates of Medicine” (1995), “Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine” (1997) and “Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise” (2002). His website is HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Rewriting the French Revolution — Part II. HaciendaPublishing.com, November 21, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/rewriting-the-french-revolution–part-ii/.

Versions of this article were also posted on NewsMax.com and LaNeuvaCuba.com.

(Leigh Ann Whaley’s “Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution” (2000, Sutton Publishing, 212 pp., ISBN: 07509-22389)

The photographs used to illustrate this article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Whaley’s Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution.

Copyright ©2004 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.