- Articles

Rewriting the French Revolution — Part I

Contrasting Revolutions

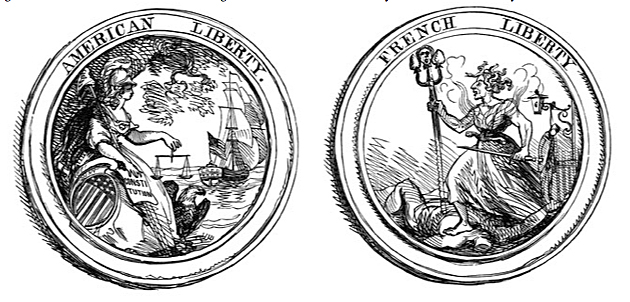

Even though politicians and some historians in both America and Europe have likened the French and American Revolutions, these two landmark events of world history were as dissimilar as the men who forged them.

The American Revolution (1775-1783) was a war for independence from England, a war for self-governance, as well as a thunderous political event that led to the affirmation of the Natural Rights of men namely, life, liberty, property and the pursuit of happiness. The American Civil War (1861-1865) freed the black slaves and extended civil rights that had been denied them since their arrival in chains to the New World.

Ordered liberty and self-determination enshrined in the American constitutional republic would endure and guide these United States of America through the turbulence of the last 200 years into the 21st century.

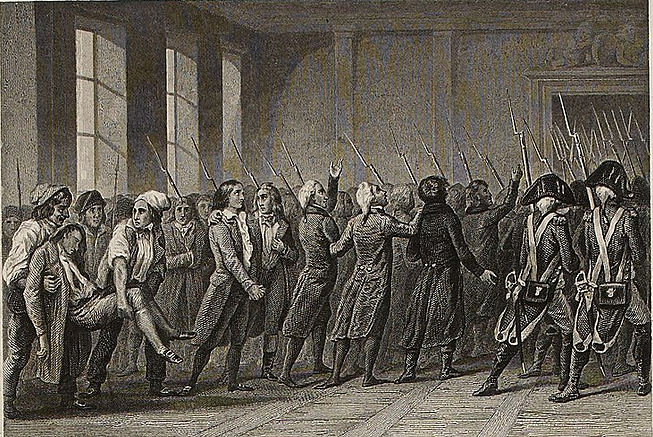

On the other side of the coin, the epochal episodes of the French Revolution, the storming of the Bastille (July 14, 1789), the fall of the monarchy (August 10, 1792), etc., were merely preludes to mob violence, the September Massacres (1792), the Reign of Terror and ultimately, the dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety and Maximilien Robespierre (July 1791-9 Thermidor, 1794).

Then came the Thermidorean Reaction, the Directory, the Consulate, and finally the Empire under the enlightened despotism of Napoleon Bonaparte (1799-1815). Mid- to late-19th-century French history continues the cycle of violence (although not of the same intensity as that of the Terror), insurrections, coups d’etat, revolutions and counterrevolutions, the rise and fall of “Republics” and “Empires,” few victories and many military defeats that would haunt France into the 20th century.

Rewriting History

In her book Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution, Leigh Ann Whaley, professor of European History at Acadia University, Nova Scotia, attempts to rewrite the history of the conflict between the radical Jacobins, the Montagnards, and the moderate republicans (i.e., the “right wing” of the National Convention), the Girondins or “Brissotins” (after one of their leaders, the journalist Pierre Brissot).

Whaley argues that the difference between these two groups was personal or tactical rather than ideological, and that this difference “was not discernible until at least December 1792.” She “rewrites the history of factionalism” as to assert that the division of the Girondins and Montagnards had more to do with personal rivalries, unfulfilled ambitions and animosities than with ideology or political objectives.

Whaley believes that it was their seeking of political support in the political struggle that led to their contrary positions, positions that evolved and “were not there from the beginning.”

Moreover, the author, contrary to all the available historical evidence (not to mention common sense!), asserts that “the uprising of 2 June [1793, when the Girondin Deputies were purged from the Convention] was not the decisive event in the downfall of the ‘Brissotins’ and the reason for their subsequent execution in the autumn of 1793.”

And then she takes the final academic plunge into the realm of the implausible. Supported with flimsy and contrary evidence, and even less convincing argumentation, she continues: “Rather, it was a combination of the illegal [my emphasis] activities carried out by a majority of those expelled … and other events, including the murder of Marat, which determined their sorry fate.”

Thus, Whaley incredibly writes of “illegality” in reference to the National Convention, a governing body that had, in fact, already rescinded whatever claims it had to legitimate governance when it approved (albeit reluctantly and under pressure) the purging of the 21 Girondin Deputies.

The Convention had cowardly caved in to the Parisian mobs and expelled the Girondin opposition, whose heads had been repeatedly demanded by the dregs of the sans-culottes, the insurrectionary Commune, and the radical Sections of Paris.

As for the assassination of Marat on July 13, 1793, Whaley buys into the propaganda of the radical Jacobins themselves, Fabre d’Eglantine, Georges Couthon, the corrupt ex-priest Chabot, and Robespierre, who used the episode as the needed, final excuse to exterminate the Girondins and their friends.

Charlotte Chorday, a genuine republican heroine, is dismissed as nothing more than a tool of the Brissotins, part of a conspiracy, when at her own trial the available evidence pointed to the fact that, even though she had met the Girondin Deputies Francois Buzot and Charles Barbaroux at Caen, she acted of her own accord, hoping that by assassinating the bloodthirsty Jean Paul Marat, she would save the Republic from the dictatorship of the Montagnards.

Significant Omissions

In the Preface, Professor Whaley curiously recommends her book to “historians of Europe” and other scholars, even “anyone seeking to understand the nature of revolutionary behavior,” but apparently not to Canadian or American historians. Why this oversight?

One wonders if she fears critical evaluation of her book from the American perspective, her Canadian colleagues, or traditional scholars, who may not share her barely suppressed enthusiasm for the men who ultimately presided over French radicalism and the bloody Reign of Terror.

Conveniently, the tyrannical and bloodthirsty careers of Robespierre, Saint-Just, Couthon, Collot d’Herbois, Billaud-Varenne, etc., of the Committee of Public Safety at the height of the Great Terror were not subject to this study. Unexpectedly, the book lowers the curtain on this dramatic performance with the execution of the “illegal” Girondins.

Yet the thesis of this book, truncated as it is, at such a critical time in the midst of the French Revolution and with such an abrupt ending, is recommended to “a multi-disciplinary audience, including students of politics, military studies and French studies.” What conclusion could these students possibly draw after such a significant omission?

A Revolution Gone Too Far

Another objection to this little tome is that all of “the Radicals” are painted with the same broad brush: They are essentially ideological Jacobins who split with each other over tactics, only to subsequently coalesce into two opposing groups.

The basis for the political realignment is, we are asked to believe, due to nothing more than petty jealousies, personal rivalries, and political necessity not ideology, or, most importantly, the realization by the moderate Girondins that the Revolution had gone too far, that the National Convention had lost legitimacy, that coercion from the Parisian mobs and the recurring and continuous threat of political violence made the task of governance virtually impossible.

This unrelenting intimidation and threat of violence, it should be pointed out, was directed almost exclusively against the “right wing” of the Convention, the moderate Girondins, who represented and were the voice of the provinces, vis-a-vis Paris and the centralization of power. Thus, a few radicals and Parisian mobs were to rule by sheer terror over a larger, more moderate country.

With good reason the Girondins feared a dictatorship of Paris over the provinces, directed by the radical Jacobins under Marat, Danton and Robespierre. History proved them correct even though the presaged brutal dictatorship lasted less than two years.

I write “painted with the same broad brush,” and yet, if anything, the bloodthirsty Marat, the despotic Robespierre, and the extremists, Saint-Just, Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois are treated with undeserved deference, bordering on admiration, as if they were French statesmen of the first order rather than the sanguinary terrorists they really became as the Revolution unfolded.

Take for instance Collot d’Herbois, radical Jacobin and member of the Committee of Public Safety, who held that for prosperity to be achieved under the revolutionary government it was necessary to sacrifice 12 to 15 million Frenchmen.

And this was not just a nightmarish idea of a mad radical; Robespierre approved of the same planned depopulation of France. He agreed with Collot that 12 to 15 million citizens needed to be exterminated before his genocidal dream of happiness in the Republic of Virtue could be consummated.

Undeserved and obsequious deference to these unsavory characters only betrays the author’s thinly veiled sympathy for these ultra-radical figures, questioning the same objectivity she seeks to attain as a historian.

Blatant Bias

Although there is no question that Whaley has done significant research, unearthing and studying original sources, she does not quote representative writings of these revolutionaries to the extent that their minds, through their own words, are opened to the critical analysis of the reader.

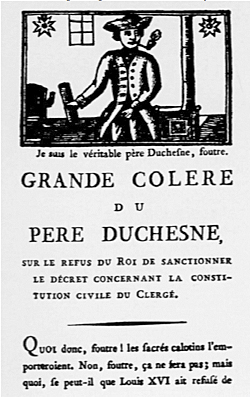

For example, Marat’s radical and frequently vulgar newspaper, L’Ami du Peuple, is never quoted even though it would have been quite illuminating to do so. Marat used these pages to harangue the Convention as well as to repeatedly ask for the blood of his enemies. Certainly, quoting his rabid writings would have set him apart from his vastly more reasonable enemies on the right.

Ditto for Rene Hebert, the cowardly and sanguinary journalist, Commune leader and radical Jacobin, who should have been specifically included in this study. Like his newspaper, Pere Duchesne, Hebert was mentioned but not quoted so as not to give us a sense of the fear the Girondins must have experienced after being denounced as “traitors” repeatedly by this editor, who again and again demanded that they face the cold blade of the guillotine!

Hebert used gruesome expressions when calling for the heads of his enemies. They should be taken to the scaffold “to sneeze into the sack” or “to look out of the Republican window.” And yet Hebert was one of the few revolutionaries (or aristocrats) who cowardly broke down when his time came and had to be taken kicking and screaming “to look out of the [same] Republican window.” Nevertheless, Hebert was only mentioned in passing, almost deferentially, as if he were only a detached witness to the revolution.

Whaley referred to the Girondin political opposition to radical Jacobin policies (supported by Marat and Hebert in their newspapers) in the National Convention as “intransigence.” The author devotes a considerable number of pages to the propaganda machine of the “Brissotin” press. The enormous influence of Marat’s and Hebert’s newspapers in mobilizing the criminal elements and Parisian mobs to influence the proceedings and intimidate the Convention is barely mentioned.

On the other hand, the Girondins, except for Marquis de Condorcet and Jerome Petion, are treated very differently. They are discredited at every opportunity, tactfully but consistently. Pierre Brissot is accused of having been a police informer, which may have been true but irrelevant, particularly when no evidence was submitted.

Hanging such a dark cloud over the reputation of a leader would surely reflect poorly on the reputation and motives of the whole political faction. Brissot may have had a shady past, but certainly the period covered under this study demonstrated him to have grown politically and morally, his courage and determination adequately expiating for his past sins.

We cannot say the same for the ultra-radical Jacobins in the Committee of Public Safety and their allies in the Insurrectionary Commune and the Paris Sections. As previously stated, a significant omission precluded analysis of the careers of the most sanguinary Montagnards in the Committee of Public Safety because the Great Terror was excluded by Whaley from the period under study!

Thus, one is left with the feeling that this book is written in an attempt to establish moral equivalence among the radicals, painting them with the same broad brush to achieve this objective. The attempt fails because historical evidence points otherwise.

Instead what the available historical evidence leads to is the fact the Girondin faction, the “right wing” of the Convention, tried but failed to bring an end to the excesses of the Revolution, an anarchic revolution gone violent and bloody.

Indeed, there is significant evidence that the Girondin leaders, Jerome Petion, Pierre Brissot, Arnaud Gensonne, Charles Barbaroux and Pierre Vergniaud, whatever their initial political thoughts, came to the realization that the Revolution had gone too far. They then intended and tried to get the Revolution on track, establish a Republic with a lawful constitution, guided by the rule of law and Natural Rights, not unlike that of the United States, which they came to admire.

Moreover, they foresaw their own destruction, and yet they fought and died bravely to prevent the coming Terror. The history of France, and, as subsequent events proved, the history of the world, could have been changed for the betterment of humanity if these courageous Girondins had succeeded.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is editor emeritus of the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons (formerly the Medical Sentinel) and author of “Vandals at the Gates of Medicine” (1995), “Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine” (1997) and “Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise” (2002). His website is HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Rewriting the French Revolution — Part I. HaciendaPublishing.com, November 26, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/rewriting-the-french-revolution–part-i/.

Versions of this article also appeared on NewsMax.com and LaNeuvaCuba.com.

(Leigh Ann Whaley’s “Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution” (2000, Sutton Publishing, 212 pp., ISBN: 07509-22389)

The photographs used to illustrate this article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Whaley’s Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution.

Copyright ©2004 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.