- Articles

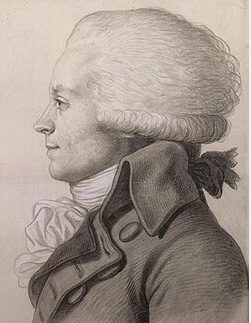

Maximilien Robespierre: Misunderstood Revolutionary or Sanguinary Tyrant? by Miguel A. Faria, MD

Maximilien Robespierre attended the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris when he was eleven years old. He apparently was “a model student” and excelled in his scholastic studies, particularly Latin. His fellow classmates referred to him as “The Roman,” because of his excellent pronunciation of Latin words and phrases. In 1775, he was chosen to “deliver a Latin address (written by a faculty member) welcoming King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette on a brief visit to the school as they returned from their coronation ceremonies at Rheims Cathedral.”

In 1781, one year after his graduation from Louis-le-Grand, where he also had received his law training, Robespierre was admitted to the bar in his hometown of Arras. His law practice provided a comfortable living, and he was professionally respected. His sister Charlotte took care of the domestic household duties and noted that Robespierre was particularly finicky about his appearance, and “spent a great deal of time contemplating himself.”

Finally, when Louis XVI called for the new Estates-General in 1788 and a list of grievances (cahiers de doléances) to be submitted from each region, Robespierre was elected as a deputy of the Third Estate from Artois and set up for Versailles. Upon arrival at the Estates-General, he became absorbed in politics and literally had “no life apart from the revolution.” In comparison to the other great orators of the time—that is, the Comte de Mirabeau, Georges Danton, and Pierre Vergniaud—Robespierre was not as impressive a speaker. Historian David P. Jordan explained:

As an orator Robespierre began the Revolution with some technical disadvantages. He spoke with a marked regional (artésian) accent. His voice, too high-pitched to be naturally pleasant, was also feeble in volume and lacked tonal variation. His physical stature was unimpressive. He was short and slight, with a large head. His weak eyes required glasses, which he sometimes pushed up onto his forehead while speaking, so he could rub his eyes. His gestures at the podium were small and a bit fussy and cramped. In a word, he lacked the presence of a great and commanding orator, and this shortcoming was accentuated by his habit of reading his speeches from a pile of manuscript, often with his head buried in his text.

Nevertheless, Robespierre worked tirelessly to overcome the technical imperfections in his speech delivery. He was highly “self-conscious about his political role,” and “that awareness shaped all his utterances.” Thus, he tended to shy away from impromptu and extemporaneous speech, and preferred “the precision that can only come with the pen.”

The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre by David P. Jordan is an idealized biography Robespierre himself would have approved of. Jordan attempted to reinterpret the career of the Jacobin leader as a more reasonable and abstract thinker whose words were misinterpreted and who should not be held responsible for the action others undertook on his behalf. Jordan explained:

I have not here attempted a biography of Robespierre but have written perhaps a species of biography, intellectual biography… I have, as one must when dealing with evidence of a literary kind, taken Robespierre at his word.

Hence, the Voice of Virtue’s collective works, Oeuvres complètes, speak to the reader through Jordan’s intermediary words—most likely the way Robespierre wanted to be heard through the ages as opposed to scholarly investigation of his actions as the central figure of the Reign of Terror. Nevertheless, his actions were important because he contributed significantly to driving the revolution down the path of radicalism and violence in the years leading up to the Terror from 1789 to 1793. But be that as it were, Jordan, like many modern progressive historians, judges and takes Robespierre at his selected words, not at where his incendiary speeches and his sanguinary actions led.

In late November 1791, a composed Maximilien Robespierre strode into the Paris Jacobin club and officially “began his campaign to forge the Jacobin clubs of France into an instrument of the revolution.” Additionally, he used the Jacobin club as the testing ground for what would become his precise formula for denunciations:

His purity gave him great moral authority…He pushed his new standards in oblique fashion by attacking various proposed candidates on a number of grounds…He proposed that a list be drawn showing a man’s present profession and his position before the revolution; his past, he said, must be “above suspicion. …He was not hampered by any rules of logic; events that occurred in the past were lumped with attitudes of the present to damn individuals…Robespierre’s first purge, though bloodless, was deadly. It destroyed men’s reputations and their political careers, branded them, and consigned them to the enemy camp.

The radical journals and pamphlets together with the lengthy speeches given at the revolutionary clubs paved the way for manipulation of the press and the learning of the methods of mass psychology, indoctrination, and incitement of mob violence.

Jean-Paul Marat took his cue from Robespierre and began “perpetual denunciations of traitors” in his journal, L’Ami du Peuple. He even went so far as to “call openly for violence against fellow Frenchmen.” Another radical journalist, René Hébert, followed suit and used his newspaper, Le Père Duchesne, to arouse and agitate the French populace.

Despite incessant references to the virtue of the people, Robespierre trusted their virtue solely as an abstract concept or when their passions could be mobilized to serve the purposes of the revolution. In his eyes, mob violence was justified if it answered his personal call to carry out political riots or revolutionary insurrections. Robespierre no longer had any further use for the mob, and his references to the people became a total abstraction.

From 1792 to 1794, the Incorruptible was instrumental in setting the stage for and presiding over the Reign of Terror. His technique was simple and time-tested—namely, the Machiavellian tactic of “divide and conquer” (divide et impera). He did so with gruesome efficiency eliminating one by one his divided opposition—first the monarchists followed by the Feuillants and the Girondins; next the Hébertists; then the Dantonists; and finally, anyone who stood in his way and the continuation of the Terror. The Incorruptible succeeded in establishing institutionalized terror as an instrument of state power. He presided over it and used it against his enemies. For him, the end justified the means.

In fact, Maximilien Robespierre, the “Incorruptible,” who presided over the Terror, history reveals, might not have worshipped on the altar of wealth and indulgence, but he certainly sacrificed human beings on the stone of abstract altruism, misconstrued ideals, and like other tyrants, to wield personal power and rule with almost absolute control, including trampling the rights of others, obliterating liberty, and presiding over mass murder because, purportedly, to create a better world, the end justifies the means.

Robespierre should be judged by historians not by his purported intentions as divined by admiring scholars or by the lofty ideals conveyed in selected passages from his writings or speeches— but by the violence that his words and denunciations incited. Robespierre was a bloodthirsty tyrant, who in the end misjudged the scornful and ferocious reaction of the desperate men around him—men who had been forced to denounce friends or associates and watch them go to the guillotine and who felt cornered, and their lives were now in mortal danger.

On 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794), the cries of “Down with the tyrant” were finally heard in the National Convention. The event resulted in a prompt and short trip to the guillotine for Robespierre and his allies. Scott is correct when he wrote:

Robespierre simply died, but folly has a virulence that outlasts its inventor. He inspired more Communes, more voices of virtue, more Vladimir Lenins, Fidel Castros, and Mao Tse-tungs, more murder and hatred, more death and misery, than any other of the sacred fools that have emerged to plague honest men.

Prince Pyotr Kropotkin (1842–1921), the foremost theorist of anarchist communism, wrote: “What we learn from the study of the Great Revolution is that it was the source of all the present communist, anarchist, and socialist conceptions.” The French Revolution (until the Thermidorean Reaction) showed the world and violently put into practice the scissor strategy of forcing radical change upon society, using fear and ultimately terror as its basis—a methodology that Karl Marx later expounded into dialectical materialism and communism. That philosophy, namely Marxism, coupled with Leninism and Stalinism, cost an excess of 100 million lives in the turbulent 20th century.

The historian Kuehnelt-Leddihn correctly acknowledge that all types of dictatorships, including Nazism and communism, were “cancerous outgrowths of the French Revolution… “Without the leading men of 1792–1794, Marx and Engels are hardly imaginable.” I concur.

Written by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is Associate Editor in Chief world affairs of Surgical Neurology International (SNI) and the author of numerous books. This article is excerpted and updated from Dr. Faria’s 2024 book Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions.

This article may be cited as: Faria, MA. Maximilien Robespierre: Misunderstood Revolutionary or Sanguinary Tyrant? HaciendaPublishing.com, April 7, 2025. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/maximilien-robespierre-misunderstood-revolutionary-or-sanguinary-tyrant-by-miguel-a-faria-md/.

Copyright ©2025 HaciendaPublishing.com