- Articles

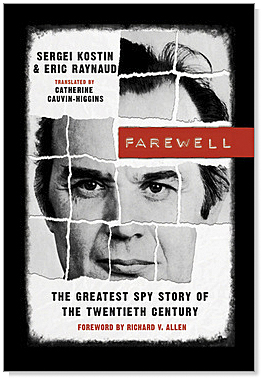

Farewell: The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud

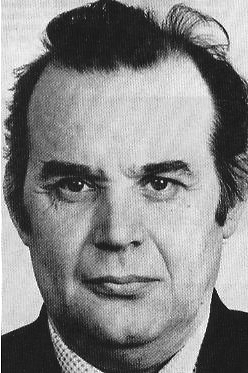

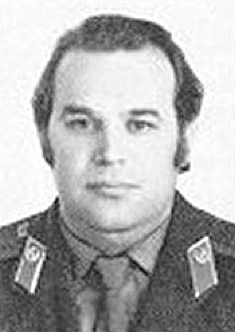

The disintegration of the USSR is inextricably entwined and intimately related to the life and times, failures and accomplishments, paradoxes and contradictions of the courageous Russian who is the subject of this book — a man with tenacious clarity of purpose and the steely determination to carry on through and accomplish his goal at any price. We are speaking of KGB officer and Russian patriot, Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Ippolitovich Vetrov (1932-1985; code name: Farewell). Vetrov crossed over to the West as a defector-in-place and spied against the KGB and his former Soviet comrades. Why? Because he was sickened by the nepotism of the apparatchiks, the abuses, corruption, and injustice plaguing the KGB specifically, and the lack of individual freedom, hypocrisy of the nomenklatura, inequalities and abuses sustained by the citizens in the entire Soviet system where family connections were more important than merit and hard work. What was his goal? To break the machinery of repression of the corrupt KGB and bring down the Soviet system, even if this task would ultimately lead to his personal destruction and death.

To comprehend the dimensions of Vetrov’s accomplishment and the global implications of the Farewell dossier, it is necessary to understand the dismal geopolitical situation of the West vis-à-vis the USSR from the 1970s up to 1981, the year of Vetrov’s revelations to France and the United States.

From 1972 to 1973, the Watergate scandal rocked the U.S. government and shook the American nation and by 1973, America had lost the Vietnam War. President Richard Nixon resigned but not before he fired Richard Helms (1913-2002), the veteran spymaster and head of the CIA (Director, 1966-1973), “the man who kept the secrets.” CIA counterintelligence (CI) had been severely hampered during this time because of the prevailing culture of paranoia engendered by the unproductive search for the mole “Sasha,” and in December 1974, CI chief James Jesus Angleton (1917-1987) was dismissed by William Colby (CIA Director, 1973-1976). To add insult to injury, in 1975 during the presidency of Gerald Ford (1973-1977), the CIA was investigated by the Rockefeller Commission and then battered by the hostile congressional investigation headed by Senator Frank Church (1924-1984). The CIA was accused of violating its charter, conducting domestic surveillance of U.S. citizens, and sanctioning assassinations in the 1960s and early 1970s. The Church Committee had indeed come dangerously close to dismantling the operational and intelligence gathering capabilities of the CIA.

Under Admiral Stansfield Turner (CIA Director, 1977-1981) during the presidency of Jimmy Carter (U.S. President, 1977-1981), the CIA suffered even more serious setbacks, including drastic cutbacks in personnel (e.g., 820 clandestine CIA officers were dismissed in the so-called “Halloween massacre” of 1977). The CIA’s powers were severely trimmed so that the agency was virtually de-fanged in intelligence and counterintelligence (CI) capabilities. As a result, America was to suffer humiliations and defeats unparalleled in her history. The Soviets and their surrogate warriors, the Cubans, were playing for high stakes. Like toppling dominoes, country after country on three continents fell prey to communism and revolution: Ethiopia fell to the communists (1973) and the revered King of the Ethiopians, Haile Selassie I, was deposed and assassinated; Mozambique (1975) and Angola (1976) also fell followed by civil wars; the Sandinistas, backed by the Cubans and Soviets, took Nicaragua in 1979; the Russians invaded Afghanistan and murdered its president, turning the country into a puppet nation and its mountainous terrain into Russian killing fields; the Shah of Iran, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, fell from power in the Iranian Revolution led by the Ayatollah Khomeini, and fled his country; finally, the economic problems facing the U.S. on top of the Iran hostage crisis, and Carter’s failed desert helicopter mission to rescue the American hostages (1979-1980), triggered a complete and general demoralization of the United States. President Carter called it a “general malaise.”

The situation was only a tad better in France. During the 1950s and 60s, France had lost most of its overseas colonies and territories after bloody or humiliating defeats in French Indochina (1954), Tunisia (1956), Algeria (1962), etc. And when France was part of NATO, Georges Pâques (1914-1979), a Soviet mole had wormed his way into the second administration of Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970), and by 1962 was revealing secret NATO defense plans to the Soviets. He was finally uncovered, thanks in part to the information revealed by Anatoli Golitsyn (1926-2008) who had defected in 1961. Pâques had been spying for the Russian communists for 20 years, embarrassing de Gaulle and further shaming France.

By the 1970s France was no longer part of NATO and had been drifting leftward in the political spectrum for some time. French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (President, 1974-1981) had been unsuccessful in fighting inflation and climbing unemployment. France, it seems, had lost her nerve in meeting domestic problems or facing the Soviet threat. The Socialists were now on the rise led by the debonair François Mitterrand, and as the elections of 1981 approached, they were ready, well organized, and counting on the support of all the leftist parties, including the Communist Party of France. The socialists tasted blood and already smelled victory at the polls. One of their goals was to at least prune if not completely dismantle and abolish the DST (Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire), France’s domestic counterintelligence service, the equivalent to America’s FBI. The socialists claimed the DST “was an instrument of the political right rather than a tool to defend the nation.” (p. 166)

Mitterrand was very skeptical of the DST and while serving as a former minister years earlier had even been investigated for suspicion of being a Moscow agent. The French foreign intelligence service, the SDECE, the equivalent to the CIA, did not even have a presence in the Soviet Union, with virtually no significant espionage or CI activity recorded against the Soviets in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Finally something thunderous and epochal happened: Ronald Reagan was elected U.S. President and took over the reigns of the U.S. government in January 1981. The Iranian hostages were immediately released from Teheran. Reagan declared his opposition to world communism and Soviet totalitarianism. He passionately believed the Soviets could be defeated if America and the West could only stop the technology transfer and cease assisting their socialist planned economies. But then on May 10, 1981, the socialist candidate, François Mitterrand, was elected President of France and vowed to appoint his communist allies to his government. The Western alliance threatened to crack, and when the Reagan administration protested and sent Vice President George H. W. Bush (a former CIA Director; 1975-1976) to the Elysée Palace, the French president publicly invoked France’s sovereignty and sent the American envoy packing. Mitterrand pleased the French public with the political gesture and did not worry about the Americans; he knew he had a magnificent trump card he would soon play with the ebullient, anticommunist U.S. president.

Suffice to say Mitterrand was confident. Two months earlier the DST had recruited a top secret Soviet mole from the Soviets’ inner sanctum, a jovial KGB officer, Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Ippolitovich Vetrov (1932-1985). The recruitment of this Russian hero by the DST is a suspenseful tale against all odds in the cause of freedom, a story beyond belief. To make matters more hazardous, the defector-in-place was recruited in the midst of the French elections by officers in the DST — i.e., the urbane Jacques Prévost, a Thomson-CSF company executive and DST liaison; the resourceful DST USSR section head, Raymond Nart; and the politically savvy and security-minded DST chief, Marcel Chalet. These courageous Frenchmen, not only acted stupendously on their own initiative, acting even without advising the administration of President Giscard d’Estaing, but made the correct decision to wait for two months until after the election to brief the new president, whoever he may be, in order to maximize secrecy and protect their asset. To the relief of the French heroes, President Mitterrand was delighted with the intelligence operation and authorized continuation of the operation by the DST under the aegis of the trusted conservative Interior Minister, and not under the SDECE (the CIA counterpart) under the Defense Ministry, which was headed by a minister who had been identified as a Soviet agent!

Very confident, President Mitterrand waited until the G7 economic summit held July 20-21, 1981 in Quebec to play his trump card. Elected as a socialist, he was a bit of the black sheep among the summit participants, as Reagan had set the tone of getting tough with the Soviets. Mitterrand and Reagan met for the first time, and the President of France showed his trump card, the magnificent Farewell dossier, which he shared with the U.S. president. Mitterrand removed any shadow of a doubt as to where he and France stood. He was squarely in the freedom camp, and Mitterrand and Reagan became instant friends. Indeed, from then on France stood with America until the collapse of Soviet communism.

During his active espionage career that lasted less than a year (from March 1981 to January 1982) but was longer than that of most agents operating in a communist police state, Vladimir (Volodia) Vetrov identified and neutralized 422 KGB officers and 54 Western agents (Soviet moles) working for the KGB and the USSR bloc. Volodia worked in France and Canada with the cover of a trade representative of the USSR, but his main task, as an illegal KGB officer, was to recruit spies and steal technological and electronic secrets from the West to facilitate Soviet research and military applications for the VPK, the Soviet Military Industrial Commission. Later, for intriguing reasons expounded in the book, he was transferred to the Center in Moscow at Yasenevo and was not allowed to travel abroad and operate in the West. But now Volodia had been placed at a key nexus point of scientific and technological information collation of the KGB, an excellent place for a French spy. And so when he decided to spy for the West and became agent Farewell, Vetrov was privy to the family jewels and needs of the Soviet state as to technologic, electronic, and scientific secrets stolen or needed from the West, including the U.S. and France. He also exposed the vast network of Soviet and Eastern Bloc organizations, which with innocuous names were front organizations also involved in pilfering science and technology from the West for the VPK.

Thanks to the Farewell dossier, the Reagan administration learned and estimated that by stealing such vast amounts of information the Soviets were able to fund their entire intelligence gathering apparatus (KGB and GRU espionage) and a large amount of their military capabilities. Reagan’s Secretary of Defense, Caspar Weinberger, stated it very clearly, “The United States and other Western nations are thus subsidizing the Soviet military buildup.” (p. 384-385) President Reagan with his trusted National Security Council (NSC) team, including Robert MacFarlane, Richard V. Allen (who also wrote the Foreword to this book), and William Casey (CIA Director, 1981-1987), were able to put together a group of intelligence officers, defense analysts, economists, and scientists who, using the Farewell dossier, fed erroneous technical and dead end scientific information to the KGB spies, duping the Soviets.

As Thomas Reed, who worked in Reagan’s NSC and assisted on the SDI project, wrote in his memoirs: “[As a grand finale] in 1984-85, the United States and its NATO allies rolled up the entire Line X connection both in the U.S. and overseas. This effectively extinguished the KGB’s technology collection capabilities at a time when Moscow was being sandwiched between a failing economy on the one hand and an American president — intent on prevailing and ending the Cold War — on the other…. Its ultimate bankruptcy, not a bloody battle or a nuclear exchange, is what brought the Cold War to an end.” (p. 387)

And it worked. Soviet leaders Leonid Brezhnev (USSR leader, 1964-1982) and Yuri Andropov (USSR leader, 1982-1984) were in a panic to save the USSR. When Reagan, assisted by Lieutenant General Daniel O. Graham announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), referred to as Star Wars by the media, the bankrupt USSR now led by Mikhail Gorbachev (USSR leader, 1984-1991) knew the game was over. To make the story short, the Soviet “evil empire,” as Reagan called the USSR in 1983, began to crack and finally came tumbling down beginning in 1989. By the end of 1991, the Soviet state had crumbled.

To learn about the man, the life and times of Vladimir Vetrov, and why he chose France as a conduit to destroy the KGB he abhorred and the Soviet system he deplored, you need to read this book. But returning to the beginning, if there is any doubt about what motivated Vetrov to spy for the West, here is the answer he wrote to the French superior as transmitted to them by Patrick Ferrant, the French Embassy military attaché who was Vetrov’s DST case officer in Moscow:

“Dear Maurice [presumably President François Maurice Mitterrand],

“Thank you for worrying about my safety. I will do everything I can in this regard. You are asking why I took this step. I could explain as follows. Sure, I like France very much, a country that marked my soul deeply, but apart from this, I detest and am appalled by the regime in place in our country. This totalitarian order crushes individuals and promotes discord between people. There is nothing good in our life; in short it’s rotten through and through.” (p. 180)

By January 1982, Vetrov was psychologically exhausted by the risk he was taking and his double existence, his personal life in shambles. On the night of February 22, 1982, Volodia and his mistress, Ludmilla Ochikina, were parked off a major Moscow highway in his Lada drinking champagne. He had been estranged from his mistress, a KGB translator, with whom he worked at Yasenevo. Apparently by a slip of his tongue due to the champagne, Volodia must have revealed he was a double agent spying for the West. He panicked, lost control, and furiously stabbed his mistress. An off-duty policeman came to the window of his Lada, and Volodia got out of his car and stabbed him too, killing the man. Vetrov was arrested for killing the policeman and attempting to kill his mistress. He was sent to the gulag, but it was a matter of time, as the KGB was suspicious of the strange circumstances of the crime and continued to investigate. The KGB’s suspicion grew as stool pigeons in the prison and gulag system reported on Vetrov’s unguarded political remarks.

Vetrov and his son Vladik had always been close. Now Volodia and his wife Svetlana, who had been very close at one time, grew together again in adversity, but the KGB was on their trail. While in prison, he still wanted to spy for the West, and he and Svetlana in desperation made grave mistakes. Concrete evidence was uncovered that he was a spy. He was made to confess and was executed January 23, 1985. When the Chief of Soviet CI, KGB officer Vitaly Yurchenko defected (and shortly re-defected) in 1985, “The Year of the Spy,” the CIA finally learned what had happened to Volodia and the information was passed to France.

Before execution, Vetrov was made to write a confession of his treason. Instead, he wrote a 60-page hand-written document, a scathing condemnation of the Soviet system and the KGB. He had died a hero. His allegiance was to freedom, the betterment of the Russian people and serving his motherland, not the KGB and the repressive Soviet system. Russia would be better served by following the ideals of liberty and the West. According to the secret document provided by Yurchenko, Vetrov “went to his death with only one regret, that he could not have done more damage to the KGB in his service for France.” (p. 360)

I would be remiss, if I did not mention some mundane issues about this book. The first version of this book was published in France in 1997, and I suspect the authors kept some material from that early version they later recognized as contradictory and implausible, but decided to retain it, notwithstanding the fact they no longer believed the emotional rollercoaster and psychologically confounding ride where that dead end, side story led. It pertains to the authors’ alleged psychological profile and asserted possible motivation for Vladimir Vetrov’s espionage and calculated, irrational, self-destructive end. These highly subjective sections — mostly speculation derived from KGB sources, “friends,” and particularly, the “confessions” of Vetrov’s mistress, “Ludmila Ochikina,” contained mostly in chapters 22, 23 and parts of chapters 24 and 30 — should had been omitted. Contradictory information and analysis in those chapters must have come from the 1997 investigation for the first version of this book. The authors subliminally admit the superfluity of these pages: “In fact, thirteen years after having written these lines, even Sergei Kostin no longer believes it.” (p. 319) And yet this superfluous and erroneous detraction speculating sinister motives was not discarded in the English version of the book published in 2011. At 430 pages, there was no need for floss, and the extra psychological analysis was a misleading redundancy. Nevertheless, this is a magnificent book and it deserves a 5-star rating.

The tome, incidentally, has relevant illustrations and helpful notes but has no index, which surprisingly is only a minor annoyance because the book, written in almost colloquial terms, has almost no need for an index anyway. Other than these two complaints —one moderate and one minor detraction, the book is a hell of a ride, a suspenseful cliffhanger with one of the most plausible explanations formulated yet for why the USSR suddenly imploded between 1989-1991, followed by the precipitous collapse of the totalitarian Soviet and Eastern Bloc communist empire.

Was Vetrov a hero or traitor? Patrick Ferrant, Volodia’s DST case officer, after he agreed to break his long silence summed up the situation in 2009 as follows: “True he committed treason, but to me he is, in fact, a patriot…Here we have a guy with his dacha, his friends, his Russian homeland. His grudge was against the KGB. He was a patriot who wanted to protect his country, the population of his country, against evil people. Was Klaus von Stauffenberg accused of being a traitor after his assassination attempt of Hitler?” (p. 389)

Indeed is a patriot one who knowingly partakes of a national evil or one whose allegiance is to goodness and what he knows to be just — as in life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — for his homeland? We must then add another name to the Pantheon of Heroes, those men and women who most immediately helped bring about the collapse of the evil empire of Soviet communism — U.S. President Ronald Reagan, CIA Director William Casey, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, French President François Mitterrand, Nobel Prize Winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Pope John Paul II, Solidarity leader Lech Walesa, Russian President Boris Yeltsin, and among other Russian heroes and patriots, defectors-in-place, Dmitry Polyakov and now Vladmir Vetrov!

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D. is Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He is an Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI), and an Ex-member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2002-05; former Editor-in-chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002). Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995); Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997); and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Farewell: The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud. HaciendaPublishing.com, April 9, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/farewell-the-greatest-spy-story-of-the-twentieth-century-by-sergei-kostin-and-eric-raynaud.

(Farewell: The Greatest Spy Story of the Twentieth Century by Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud (2011). Translated by Catherine Cauvin-Higgins. AmazonCrossing, Las Vegas, Nevada, 430 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive book review for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Kostin and Raynauad’s Farewell. An unillustrated version of this book review was published in GOPUSA on April 26, 2013.

NOTE: A French film — L’affaire Farewell — was made based on the Farewell dossier and released in 2009, the English version in 2010. It has received excellent reviews, featuring Guillaume Canet (playing Patrick Ferrant, as “Pierre Fremont”) and Emir Kusturica (playing Vetrov, as “Gregoriev”). The film is well done and for the most part encapsulates the substance of the Farewell Dossier. Unfortunately, toward the end, the film is suddenly subject to the left-wing politics of the producers, and the denouement is outlandishly marred by a totally fabricated ending, in which the CIA (represented in a rare appearance by Willem Dafoe playing the CIA Director), the U.S., and the American President (Fred Ward playing President Reagan) are slandered and smeared by betraying Farewell! This is a very mendacious ending (with no basis at all in fact) for an otherwise excellent film. The movie review is available from: Classic movies and documentaries.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.