- Philosophy and History

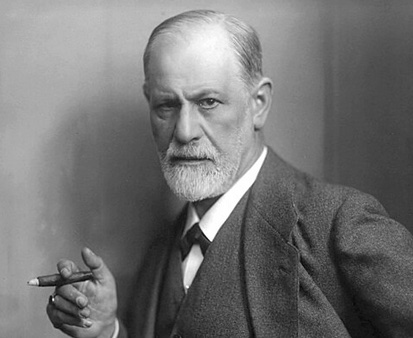

Civilization and Its Discontents by Dr. Sigmund Freud—Reviewed by Miguel A. Faria, MD

For this summary and review of Dr. Sigmund Freud’s work, we refer to the authorized translation by Joan Riviere (1930). Freud began his narrative inspired by the critical words of a friend, who although agreeing with Freud in the issue of religion, disagreed with the father of psychoanalysis for “failing to appreciate the ultimate source of religious sentiment.” Furthermore, Freud took issue with his friend’s “feeling that religious sentiment gave a sensation of ‘eternity,’ of “something limitless, unbounded, something ‘oceanic.’ ”[p. 7]

Freud said that “he cannot discover that ‘oceanic’ ” feeling in himself [p. 8] and this difference of opinion launched him fully into his book, Civilization and Its Discontents discussed in the following pages.

He reviewed known psychoanalytical territory: the ego, the id, and their interactions with the inner (self) and outer (society) world; the primitive “pleasure principle” beginning in infancy and growing into adulthood; the “reality principle of the ego,” and the boundaries of these last two.

According to Freud, with regression therapy, perhaps, we could be apt to recall forgotten memories once considered to have been lost.[p. 14-15] But, as with many statements he made in this essay, Freud was not quite so sure: “Perhaps we should be content with the assertion that what is past in the mind can survive and need not necessarily perish.[p. 20] No one can disagree with that; Freud treads here on safe ground. Furthermore, Freud surmised the ego-reality principle extending to the outer world and wanting to rejoin it is the source of the unbounded “oceanic” and “eternity” feelings, “an early stage of ‘ego-feeling.’ ”[p. 20] So the ideational content of the “oceanic” feeling and the oneness with the universe of his friend eventually becomes after all related to religion: “The derivation of a need for religion from the child’s feeling of helplessness and the longing it evokes for a father seems to me incontrovertible.”[p. 25]

While Freud actually thought he had remained a neutral commentator, his aversion to religion, particularly Christianity—and as we shall see, to the “unnatural” constraint society places on sexual freedom and even to man’s “innate aggression”—is surprising and disturbing. As for religion, it was derived from the primeval exalted father, which he discussed at length in Totem and Taboo (1919). But here, though, in dealing with modern man, and not the primitive band of the primal horde, he summarized the issue as follows:

[H]is religion, that system of doctrines…that explains this riddle of the world with an enviable completeness and that assures him that a solicitous Providence is watching over him and will make up to him in a future existence for any shortcomings in this life. The ordinary man cannot imagine this in any other form but that of a greatly exalted father, who understands the needs of his sons or be softened by their prayers and placated by the signs of their remorse. The whole thing is patently infantile, so incongruous with reality, that to one whose attitude to humanity is friendly it is painful to think that the great majority of mortals will never rise above this view of life.[p. 23]

Freud admits that for better or for worse, only religion can answer the question of the purpose of life.[p. 26] And yet, neither society (referred in this book as the “culture”), nor religion and the “scheme of Creation,” take into account that the major concern of man is the attainment of happiness in the form of “intense pleasure” or “unbridle gratification of all desires,” or at the very least the avoidance of pain. Psychoanalysis explains this goal as the ego-pleasure principle, which dominates the operation of the mind “from the very beginning.” Suffering is the lot of man by the impositions and restrictions of society and communal life upon the individual.[p. 27]

When the outer world, with which the ego has to contend, constrains man in the attainment of happiness with insufferable rules of conduct, suffering is the result. Thus, these basic instincts (“needs”) in men are suppressed by the reality principle that comes into play.[p.32] Freud tells us that psychoanalysis has acknowledged that the gratification of man’s most primitive instincts is happiness, especially pleasures that are brought about by the “irresistibility of perverted impulses, perhaps the charms of forbidden things.”[p. 33]

Few mechanisms can protect men from suffering brought about by the constraints against happiness enforced by the reality principle. Among the mechanisms to protect men from pain and suffering is libido displacement in the form of sublimation. Work, besides the fact that it is indispensable for subsistence, would seem an excellent activity to make an individual bound to reality and the community by interacting and even “discharging libidinal impulses” with others—especially when work is selected by choice, but Freud correctly reminded us that “the great majority work only when forced by necessity, and this natural aversion to work gives rise to the most difficult social problems.”[footnote, p. 35]

In short Freud asserted, “The goal towards which the pleasure-principle impels us—of becoming happy—is not attainable.”[p. 39] This is in part due to the mental constitution of the individual, the choices he makes for gratification, erotic or otherwise, and his interaction with the outer world. For some individuals there is “substitute-gratification,” especially in the young, who may take flight into neurotic illness, particularly anxiety-neurosis, psychosis being the final refuge.[p. 41]

At the end of this section, Freud cannot refrain from taking another shot at religion (really Christianity), although as an asteism, admitting that in its “forcible imposition of mental infantilism and inducing a mass delusion—religion succeeds in saving many people from individual neurosis.”[p. 42]

In the next section of his essay, Freud confronted “the social source of our distresses,” which he attributed to our culture and the advent of civilization.[pp. 41-64] He asked rhetorically, “How has it that so many people have adopted this strange attitude of hostility to civilization?”[p. 44] Looking at the converse side of the argument, Freud then began to answer the question by enumerating the many advantages and benefits that man has derived from culture and civilization: From the discovery of fire and making tools to general scientific and practical progress in which man gained power against nature, making his life easier and safer; cleanliness, order, time for the contemplation of beauty and philosophy; communal life with the pursuit of justice and equal laws for all, et cetera[p. 60]—only later to take it back for not granting freedom and happiness.

Despite these magnificent accomplishments, man has not gained pleasure or long-term happiness. According to Freud, liberty was not one of the benefits of culture; instead, Freud raised nebulous objections, “liberty has undergone restrictions through the evolution of civilization…and the desire for freedom [is] maybe a revolt against some existing injustice… Thus, the cry for freedom is directed against particular forms or demands of culture or else against culture itself.”[p. 60]

Freud seemed convinced that the cry for individual freedom is directed against communal culture itself—man “will always defend his claim to freedom against the will of the multitude.[p. 61] One reason for man to carry this hostility to society and his instinctual yearning for liberty is cultural development. Freud wrote, “it is impossible to ignore the extent to which civilization is built up on renunciation of instinctual gratification.”[p. 63]

In the next section, Freud expounded on the communal life of primitive man, using theoretical material from his book Totem and Taboo. Thus, the primal band of brothers imposed communal law—in which compulsion of work was established as a necessity and the bonding forged by erotic law with the male wanting to keep the female as a sex object and the female seeking protection for herself and her infant—held the community together.[p. 68]

But soon after, man found that “sexual (genital) love afforded him his greatest gratification so that it became in effect a prototype of all happiness to him…to make genital eroticism the central point of his life.”[p. 69]

In time, two types of love developed. Sensual (genital) love led to families. Women represented “the interest of the family and sexual love,” opposed to the all-embracing or “aim-inhibited” love which led to friendships and cultural activities and the communal work of civilization that became “men’s business.”[p. 73] Thereafter, the tendency of culture was to restrict more and more sexual life. Freud claimed that the band of brothers at the earliest totemic phase of culture imposed “the prohibition against incestuous object-choice, perhaps the most maiming wound ever inflicted throughout the ages on the erotic life of man.” Subsequently, further restrictions followed in the forms of taboos, laws, and because of “fear of revolt among the oppressed.”[p. 74]

In time, sexual restrictions mounted, particularly reaching a “high-water mark” in Western civilization, according to Freud, who lamented society’s “censuring any manifestations of the sexual life of children…and its actually denying the existence of these manifestations.”[p. 74-75]

Even sanctified marriage does not escape criticism of Freud’s alert societal eyes: “But the only outlet not thus censured, heterosexual genital love, is further circumscribed by the barriers of legitimacy and monogamy…”[p. 77]

Moreover, the father of psychoanalysis went on to say, “sexual relations are permitted only on the basis of a final indissoluble bond between a man and a woman.”[p. 75] Freud would be surprised by the societal changes, not always beneficial, that have taken place in the last one hundred years, particularly since the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.

Freud lamented that society ignored “man’s bisexual disposition,” and that man’s theory of instincts remained unconnected with this fact. After all, Freud believed that sexuality, anal eroticism, and excitation of the genitals by the strong sense of olfaction has been repressed in modern society as “the adoption of the erect posture [brought about] a lowering in value of the sense of smell.” Repression of this primeval animal instinct has even “brought obstacles in the way of full satisfaction and forces it away from its sexual aim towards sublimation and displacement of the libido.”[p. 78]

Pairs of satisfied men and women tied to each other solely as propounded in civilized community has never existed and will not fulfill sexual desires or libidinal satisfaction, “exacting a heavy toll of aim-inhibited libido in order to strengthen communities by bonds of friendship between members.”[p.80]

In the next section, Freud, who has alluded to be a friend of the plight of humanity, showed, nevertheless, a strong misanthropist streak. He took issue with, or rather, as his thoughts developed, took offense “at the so-called ideal standards of civilized society and Christianity’s command, “Thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself.” The command, rather than being an exalted ideal to strive for, “imposes an obligation on me which I must be prepared to make sacrifices to fulfill.”[p. 81] And thus presumably, Freud could not morally conceptualize, much less strive, to fulfill it.

Most realistically, a second command aroused a stronger revulsion in Freud: “Love thine enemies.”[Matthew 5:43-44.] Freud responds with credo quia absurdum (“I believe because it is absurd”). In fact, Freud has a counterargument to those in society who believe in those biblical commands because they naively believe that “men are gentle and friendly creatures wishing for love.” Instead, Freud argued, “men have a powerful measure of desire for aggression that has to be reckoned as part of their instinctual endowment”[p. 85] and that society has more realistically dealt with this problem in place of formulating those commands.

Freud insisted, “Civilized society is perpetually menaced with disintegration through this primary hostility of men towards each other. Their interests in their common work would not hold them together; the passions of instincts are stronger than reasoned interests. Culture has to call up every possible reinforcement in order to erect barriers against the aggressive instincts of men…”[p. 86]

Freud does not clearly commit himself to disapprove some of these methods, but for better or for worse, society has kept these desires in check, such as the promotion of communal friendships (“aim-inhibited love-relationships”), “restrictions in sexual life, and the ideal command to love one’s neighbor as oneself.”[p. 87]

The communist belief that private property (and its result, oppression) is the cause of man’s hostility and that its abolition and man’s social equality, would bring happiness and justice is “an untenable illusion.”[p. 88] Physical and mental inequalities, scanty possessions and privations, as well as aggressiveness, have been part and parcel of the lot of man since primeval times. Aggressiveness and possessions, affirmed Freud, have always been with man, and have been “at the bottom of all relations of affection and love—possibly with the single exception of that of a mother to a male child.”[p. 89]

In small communities, posited Freud, “the aggressive instinct can find an outlet in enmity toward those outside the group.” Unlike Christianity united, Jews having been scattered throughout the world rendered services and cultural developments in the various communities where they settled. And yet, according to Freud, “Once the apostle Paul had laid the foundation of his Christian community, the inevitable consequence in Christianity was the utmost intolerance towards all who remained outside of us.”[p. 91]

In the next section, Freud cited Schiller’s aphorism that hunger and love make the world go around. Hunger serves the instinct of self-preservation, whereas love protects the species. Freud then proceeded to recapitulate basic psychoanalytic theory: Object instincts led to the libido (and libidinal instincts), but the preservation of the self led to the ego instinct. In the struggle between the self and the libido, “the ego was victorious at the price of suffering and renunciation.”[p. 95]

Freud then carried the instinct of aggression a step further toward an instinct of self-destruction, positing the existence of a death instinct. Sadism and masochism were aspects of Eros (eroticism) and sexuality mixed with individual self-destruction, but he admitted this admixture, especially the addition of the death instinct, received opposition from psychoanalytic circles and was not completely accepted.[p. 97-99]

In the next section, Freud postulated that another method by which society combats aggression is by internalizing it, that it is “introjected,” meaning “sent back to where it came from, i.e., directed against the ego.”[p. 105] The, superego, formerly part of the ego, now developed into conscience, entered the psychoanalytic picture. The tension between the demands of the strict superego and the subordinate ego results in guilt, which in turn manifests itself as punishment.[p. 105]

Initially, as in a child, the fear of losing love is the origin of guilt because of man’s sense of helplessness and dependence on others—“social anxiety.” As the community takes the role of father, some individuals do bad deeds to obtain whatever they desire. These habitual transgressors fear only detection, not guilt, in their social anxiety—that is until the development of the superego and the internal conscience. At this stage the superego “torments the sinful ego with the feeling of dread” from punishment to be inflicted by the outer world.[p. 108]

Conscience is the source of the feeling of holiness and sinfulness. And curiously, noted Freud, “it is precisely those people who have carried holiness farthest who reproach themselves with the deepest sinfulness.” Art, this time imitating psychoanalysis and biblical theology, sometimes accurately portrays this phenomenon. I have a beautiful and poignant painting of the ascetic Saint Jerome in his study with his books being tempted by the apparition of a beautiful nude woman, which reminded me of Freud’s assertion, “temptations do increase under constant privation, whereas they subside if they are sometimes gratified.” Moreover, “misfortune, i.e., deprivation greatly intensifies the strength of conscience in the superego.”[p. 110] This affirmation in turn reminds me of the Christians stern resolve to bear pain and death in holy martyrdom during their persecution by Nero and other emperors before conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity.

Freud’s own discussion then led him to the realization that the ultimate sources of guilt arouse from “the dread of authority and then later from the dread of the superego. The first one compels us to renounce instinctual gratification; the other presses over and above this towards punishment, since the persistence of wishes cannot be concealed from the superego.”[p. 111]

Freud tied this discussion of anxiety, guilt, and conscience with basic psychoanalytic theory and the origin of culture: “We cannot disregard the conclusion that man’s sense of guilt has its origin in the Oedipus complex and was acquired when the father was killed by the association of the brothers (see Totem and Taboo). At that time the aggression was not suppressed but carried out, and it is the same act of aggression whose suppression in the child we regard as the source of feelings of guilt.”[p. 118]

The man’s feeling for the murder of the father is remorse, “the result of the earliest primal ambivalence of feelings to the father: the sons hated him, but they loved him too.” The superego was set up by the remorse after the impious act had been committed, authorized to use “the power of and identified with the killed father.”[p. 120] These ambivalent and repressed feelings persist in later generations engendering guilt and anxiety. Freud connects these feelings “to the eternal struggle between Eros (love) and the destructive or death instinct,” but most psychoanalysts reject this later connection. We are left to contend with the well-founded psychoanalytic concepts of ambivalence, repression, guilt, anxiety neurosis, and the problems facing the individual with the evolution of culture.

Freud is again highly critical of the upbringing of children. Society conceals from them the part that sexuality will play in their lives, told that people are good and demand they should be good. Thus, they are “not prepared for the aggressions of which they are destined to become the objects.”[footnote. p. 124]

Freud believed that the sense of guilt is humanity’s fundamental problem in the evolution of culture, and that “the price of progress in civilization is paid in forfeiting happiness through the heightening of the sense of guilt.”[p. 123-124] The guilt produced by culture is not recognized as such, remains repressed in the unconscious resulting in unhappiness and expressed in some individual as anxiety neuroses.[p. 126] It is the thwarting of the need for instinctual gratification that results in guilt and in expressed or repressed (“turned inward”) aggression.[p. 128-130]

As to unfulfilled erotic desires, Freud asserted, “The thwarting of erotic gratification provokes an excess of aggressiveness against the person who interfered with the gratification, and then this tendency to aggression in its turn has itself to be suppressed.”[p. 131] Anxiety results from thwarted gratification, unconscious sense of guilt, and repression. The symptoms are “essentially substitutive gratification for unfulfilled sexual wishes,” and “when an instinctual trend undergoes repression, its libidinal elements are transformed into symptoms and its aggressive components into a sense of guilt.”[p. 132]

Two trends dictate the civilizing process of man. One is towards the development of the individual, which is attained by the “egoistic” pleasure-principle and the attainment of happiness. The other impulse is the “altruistic” or cultural trend, which seeks to merge the individual with others in the community imposing unity and restrictions for the sake of the whole.[p. 134] There would be a long and intense conflict between these two trends because they seemed irreconcilable. In the meantime, argued Freud, while culture seeks a solution, man will continue to suffer.[p. 136]

In the treatment of the neuroses, Freud “found fault with the superego of the individual on two counts: In commanding and prohibiting with such severity it troubles too little about the happiness of the ego, and it fails to take into account sufficiently the difficulties in the way of obeying it—the strength of instinctual cravings of the id and the hardships of external environment.”[p. 139] As for the societal restrictions, “Exactly the same objections can be made against the ethical standards of the cultural superego. It too does not trouble enough about the mental constitution of human beings.”[p. 139] Man’s egos do not have unlimited power over the primeval urges of the id. Even in normal persons, “the power of the ego cannot be increased beyond certain limits”—pushing beyond those limits produce unhappiness or anxiety neuroses.

Freud offered no judgment about the ultimate value and future of our civilization: “I have endeavored to guard myself against the enthusiastic partiality which believes our civilization to be the most precious thing that we possess or could acquire.”[p. 142] The father of psychoanalysis does not offer any solution or guidance for the problem of cultural evolution precipitated by “the derangement of communal life caused by the human instinct for aggression and self-destruction,” nor does he offer any consolation for the fate of man and civilization: “my courage fails me, therefore, at the thought of rising up as a prophet…and I bow to their reproach that I have no consolation to offer them.”[p. 143] And so, he left the problem unsolved and the enigmatic solution to be solved by future generations.

Book Review written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is the author of numerous books, including, Cuba’s Eternal Revolution through the Prism of Insurgency, Socialism, and Espionage (2023); Stalin, Mao, Communism, and their 21st-Century Aftermath in Russia and China (2024); Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions (2024); and his last book, The Roman Republic, History, Myths, Politics, and Novelistic Historiography (2025) —the last five books by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

This article may be cited as: Faria, MA. Civilization and Its Discontents by Dr. Sigmund Freud—Reviewed by Miguel A. Faria, MD. HaciendaPublishing.com, Jun 4, 2025. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/civilization-and-its-discontents-by-dr-sigmund-freud-reviewed-by-miguel-a-faria-md/.

Copyright ©2025 HaciendaPublishing.com