- Articles

Book Review of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine: Historic Perspectives on the Battle Over Health Care Reform. Reviewed by David A. Hyman, MD, JD

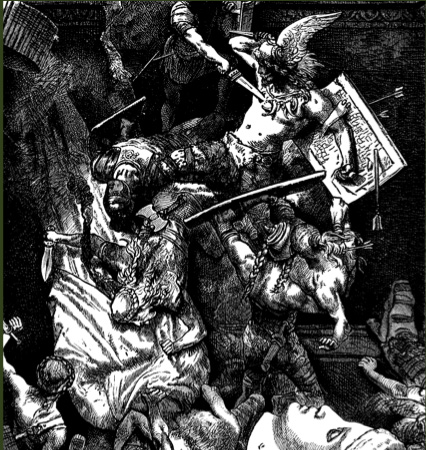

How is one to describe a book in which chapter I begins with the words “In the beginning” and that then proceeds to discuss, in 32 chapters, the history of humanity and the development of medicine and medical ethics — up to, and including, the ill-fated Clinton health plan? The book has been written by a practicing neurosurgeon with wide-ranging interests. Its sweep through history is demonstrated by the 30 photographic plates of such mythological and historical figures as Osiris, Hippocrates, and Vesalius. The political leanings of the author, who escaped Cuba at the age of 13, are demonstrated by two other plates — one of him interviewing a wounded Salvadoran soldier, and another of his wife holding a SAM-7 missile launcher captured from a Nicaraguan plane transporting weapons to the Salvadoran guerrillas.

The book presents a conservative critique of modern efforts at reform of the health care system, along with a comprehensive historical review that Dr. Faria claims demonstrates the dangers of uncoupling private initiative and free markets from the provision of health care services. The principal target of the book is the Clinton health plan, but there are a host of other villains and evil forces in Faria’s analysis, including lawyers, bureaucrats, practitioners of defensive medicine, the American Medical Association, laws governing medical and product liability, the media, liberalism (in general and in academia), egalitarianism, domestic socialism, and all the forces favoring the redistribution of income and property. The rhetoric is impassioned, in line with the sense of urgency in the title. Faria no doubt views the defeat of the Clinton plan in Congress with considerable satisfaction. Yet, as the list above reflects, he has a host of other matters of concern, apart from those relating to health care policy.

There is much to appreciate in this book. In relatively few pages, Faria has provided a compressed history of humankind, focusing principally but not exclusively on Western civilization. The book also gives a quick overview of the history of medicine and surgery. Those looking for an accessible yet wide-ranging introduction to these areas could do far worse.

Faria’s chief complaint is that the government has increasingly intruded into the practice of medicine, by (among other things) its oversight over credentialing, reimbursement practices, the National Practitioner Data Bank, and monitoring of outcomes. In Faria’s view, such matters would be better left to individual patients and to the medical profession. Certainly, government at all levels has steadily increased its involvement in medicine — particularly since the government has become a major source of funds for health care. One might certainly argue about the necessity or appropriateness of particular kinds of oversight, let alone a forced transformation of the health care economy. However, it is naive to expect that the purchaser of such a large proportion of health care services would not impose strictures of some sort, particularly given the growth in the budgets of entitlement programs. The government, like any other buyer, albeit within constitutional constraints, is entitled to attach whatever conditions it chooses to its purchases.

Faria’s analysis is also overly parochial. As the latest headlines reflect, the health care economy is in the midst of a major restructuring in which many of the changes feared by Faria have taken place without the intercession or the government. Health maintenance organizations and managed-care plans have become the dominant mechanisms for the provision of health care, and integrated health care networks have steadily displaced private practitioners. This transformation of health care from cottage industry to consolidated market has limited access and circumscribed professional discretion. By focusing his complaints solely on governmental intervention, the author does not address the most important cause of recent limitations on professional autonomy — market forces — although these forces are fully consistent with his preference for private markets.

The book could have benefited from tighter editing and better organization. The narrative switches frequently between the ancient past and the immediate present — often without good reason. A chapter on the legacy of republican government, the rule of law, and the wisdom or the founders of the American republic appears in the section on Rome. Chapters on modern medical ethics and “egalitarian ethics and other socialist scandals” come before sections on the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. There is also some degree of repetition in the discussion of key figures and events.

On balance, this book is worthwhile, particularly for those interested in the history of medicine and Western civilization. If you have not studied history since high school or college, you will be surprised at the “ripping yarns” in this book. The other aspect of the book is its presentation or the apocalyptic version of conservative doctrine. On this score, Faria’s analogy between modern events and history is overstated. His analysis cannot explain why private initiative has led to a restructuring of the health care economy similar to the one sketched out in the Clinton health plan — particularly since his conclusion, based on history, is that such changes come about only when the masses arc bought off by demagogues. At last check, the changes most reared by Faria have resulted from the action or the invisible hand, not the forces of government.

Reviewed by David A. Hyman, MD, JD

University of Maryland, School of Law

Baltimore, MD

Reprinted with permission from The New England Journal of Medicine, February 23, 1995 — Vol. 332, No. 8, p. 542-543.

Copyright © 1995, Massachusetts Medical Society.