- Articles

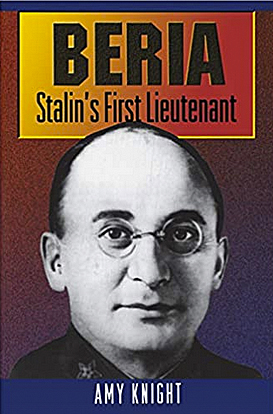

Book Review: Beria — Stalin’s First Lieutenant by Amy Knight

“As Lavrenti Beria stood over Joseph Stalin’s deathbed in early March 1953, witnesses observed that he could barely contain his pleasure in watching the leader edge toward his final moments of life.”

Beria — Stalin’s First Lieutenant by Amy Knight is a well-written, exemplary biography that attempts to “challenge some basic assumptions” about Lavrenti Beria and his role in Stalinism and terror from the time of the October Revolution of 1917 to his execution in 1953. Robert C. Tucker, Professor Emeritus, Princeton University, has called this book “the first full-scale scholarly biography of Stalin’s clever, cruel and domineering security chief.”

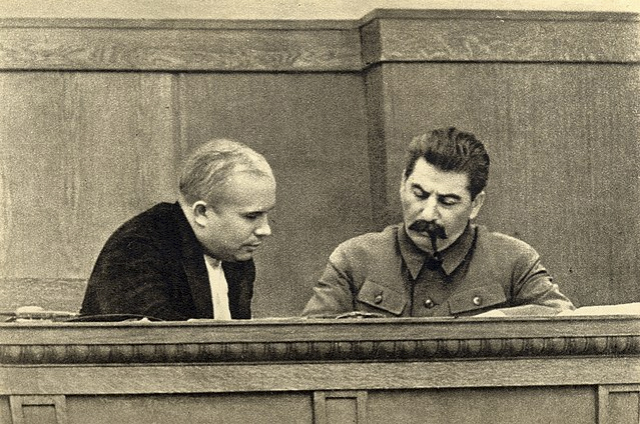

Amy Knight, a Senior Research Analyst at the Library of Congress, has a gift for elegant writing and turning revealing phrases, as well as for having a keen understanding of the psychopathology of Soviet leaders, particularly Nikita Khrushchev, Joseph Stalin, and the subject of this biography, Lavrenti Beria.

Stalin surrounded himself with malleable bureaucrats and communist minions to whom he applied the effective strategy of “divide and conquer,” so as to threaten their own existence with physical annihilation in a climate of suspicion that deterred disloyalty on the part of his lieutenants.

But Lavrenti Beria was not the typical unimaginative follower. As an astute operative and a fellow Georgian steeped in Georgia’s ideals of loyalty, betrayal, even fears of death, he quickly divined his compatriot’s psychopathology. Beria could penetrate Stalin’s mind and by nurturing Stalin’s fears and paranoia and his unquenchable need for praise, Beria was able to use that for his own purposes not only to effect his survival but also to accumulate power.

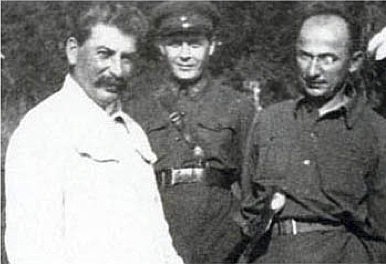

Stalin and Beria were both from Georgia, however from different regions of Georgia. Beria was 20 years Stalin’s junior. A member of the next generation of Soviet leaders, Beria had no qualms about helping Stalin exterminate the old Bolsheviks who could challenge Stalin’s power or his version of Revolutionary history, particularly when “the Great Leader” had set out to re-write and correct history, so as to fit with his unfolding, grandiose cult of personality and historical revisionism.

While Beria could use the most extreme measures of repression against his own countrymen, unlike Stalin, he remained close to Georgia and protected as much as possible his private fiefdom in the Transcaucasia, which included Armenian, Azerbaijan, as well as Georgia. Stalin became a Russian and overtly left Georgia behind embarking on his harsh Russification policy at the expense of the various nationalities, including Georgians.

Unlike Beria, Nikita Khrushchev ran his fiefdom in the Ukraine without concern for his countrymen, and did nothing to protect that region from the Bolshevik and Soviet onslaught.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Beria was police chief (NKVD) and party leader in Georgia and Transcaucasia. He won Stalin’s confidence by enforcing his repressive measures, including the great leader’s rapid industrialization of urban areas at the expense of the compulsory requisitioning of crops and foodstuff from the peasantry, while forcing collectivization of their farms (kolkhozes).

Beria also promoted and furthered Stalin’s personality cult to dizzying heights. Beria managed to survive the “Yezhovina,” the Great Terror of 1936-38, even though he came close to becoming one of its victims. In 1938, Nikolai Yezhov, NKVD chief in Moscow, ordered the arrest of Beria who was party chief in Georgia, but Georgian NKVD chief Sergei Goglidze, one of Beria’s trusted protégés (later dubbed the “Georgia Gang”), warned him.

Beria bid goodbye to his family at the airport, expecting to be arrested and executed; but rather than accepting that fate, upon arrival in Moscow, he convinced Stalin that his life should be spared, reminding the vozhd (“the Great Leader”) what a loyal and useful lieutenant he had been and how exact and efficiently he had carried out party orders in Georgia and Transcaucasia. Shortly thereafter, Yezhov was himself purged and Beria became the new NKVD chief!

Beria quickly insinuated himself into Stalin’s inner circle and became the most powerful security chief in the Kremlin virtually until his fall in 1953.

As chief of Stalin’s secret police, the NKVD, Beria was not only nearly omniscient and omnipotent in the Soviet communist pantheon just below Stalin, but also bore responsibility for internal repression, foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, and ran the concentration and slave labor camps of the Gulag, the system so well described in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago.

With the advent of World War II, Beria assumed the titanic task of evacuating the Russian defense and armament industries and moving them eastward as the German Wehrmacht advanced.

In 1945 at the end of World War II, Stalin placed Beria in command of the Soviet atomic bomb project, including responsibility for atomic espionage, liaison with the Russian scientists assigned to the ultra secret project, such as Igor Kurchatov, Petr Kapitsa, and Andrei Sakharov (later to become the father of the Russian hydrogen bomb).

Beria was also in charge of the sharashi, the special NKVD research centers for various projects, where prisoner scientists were forced to work under the auspices of the NKVD. It was work as a trained mathematician and physicist that saved the life of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in one of these sharashi while in captivity in the Gulag. Solzhenitsyn’s experience was described in fictionalized form in his masterpiece, The First Circle.

Nevertheless, timely testing and production of the bomb were his first priorities between 1945 and 1949. Beria completed these tasks with incredible success, leaving the West astounded at the Soviet achievement, several years ahead of the timeline expected from American intelligence. He achieved full politburo membership in 1946 and was awarded the Order of Lenin for his success in 1949.

During all this time, Beria saw that Georgia and his native region of Mingrelia were protected as much as possible from the economic turbulence of the times, and made sure that his political allies governed in all of Transcaucasia.

Ms. Knight expounds on the rise of the man who became Stalin’s first lieutenant in maintaining communist orthodoxy in the first eight chapters, but then after Stalin’s death in the remaining chapters attempted to liberalize the Soviet Union too fast, which proved to be his downfall.

After the war with Hitler had been won, from 1950 to 1953, Stalin was once again ready to stoke his system of repression and re-implement terror on a grand scale, this time designed to include the repression of Russian Jews, the purging of his security apparatus and even members of his inner circle. Toward this end, Stalin concocted a series of conspiracies; some were even interrelated, and only he, the master conductor, knew as to where they led and his ultimate objective. These concocted plots included the “Leningrad Affair,” the anti-Semitic, anti-Cosmopolitan campaign, and “the Jewish Doctors’ Plot” that enmeshed Jewish intellectuals, communist party members, state security organs, Kremlin doctors, and even his loyal and long-time chief of his personal bodyguards, General N. S. Vlasik.

Stalin even began to mistrust Beria, and toward this end, he concocted the so-called “Mingrelian conspiracy,” that in Stalin’s paranoid mind involved corruption of political leaders in Georgia (allies and protégés of Beria) and a treasonous separatist “bourgeois nationalist” movement with ties to Turkey.

In his inner circle only Georgi Malenkov and the newer members Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin still enjoyed Stalin’s “confidence,” but this trust hung capriciously over their heads like the Sword of Damocles. Suspicion had fallen already over his former comrades V. Molotov, K. E. Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, Anastas Mikoyan, and Lavrenti Beria. It seems that the turmoil of the Jewish Doctors’ Plot and the Mingrelian affair were the final strokes for Beria, who, perhaps with the connivance of Malenkov and Khrushchev, decided to act to protect their lives.

Immediately after Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, Beria moved rapidly to seize power. And almost as suddenly, he became a liberal political reformer. He defended the rights of non-Russian nationalities, such as the Ukrainians and Georgians, vis-à-vis the former Russification policy of Stalin. He admitted that both the Jewish Doctors’ Plot and the Mingrelian affair were concocted by Stalin’s underlings, and had those involved arrested.

Beria then began to decentralize and dismantle the secret police and the Gulag system as part of his broader program of liberalization. He granted amnesty to a large category of Gulag political prisoners. With the repudiation of the Doctors’ Plot, the doctors were released from prison, and the campaign of anti-Semitism was ended. Under Beria, de-Stalinization had begun at a faster pace than would be reestablished later under Khrushchev.

The crisis in East Germany, though, provided the pretext that Nikita Khrushchev needed to challenge Beria’s power in the Kremlin. Malenkov, who had been Beria’s ally, was won over by Khrushchev’s intrigues, as were some important segments of the Russian military, which had come to resent the prominence of Beria and his secret police.

In the face of economic problems in East Germany in May 1953, Beria recommended a radical liberalization policy that included “the abandonment of the forced construction of socialism,” “work toward the creation of a united, democratic Germany,” stop the compulsory collectivization of agriculture, and end the policy of eliminating private capital in the economy. Additionally, Beria replaced the Russian military commander in East Germany with a civilian commissioner.

But Beria had made a mistake. He had moved too fast in the liberalization of East Germany. The iron-fisted East German Chancellor Walter Ulbricht opposed the reforms, and the contradictory statements confused the issue, creating instability and fueling public discontent. Influenced by Beria’s intended reforms, East German protestors, whose objectives now included not only economic liberalization but also the removal of the hard-line, communist Chancellor Ulbricht, took to the streets. By June 17, 1953, Soviet tanks were rolling into East Germany to crush the rebellion.

Georgi Malenkov, who now supported Khrushchev, along with Nikolai Bulganin and V. Molotov, blamed Beria for the crisis in East Germany.

Amy Knight correctly asserts that “the East German crisis provided Khrushchev with the pretext for rallying opposition against Beria,” and that Khrushchev and Molotov would later denounce Beria’s program at the July 1953 Central Committee Plenum, “accusing him of turning against socialism and playing into the hands of the West by trying to create a united, neutral bourgeois Germany.”

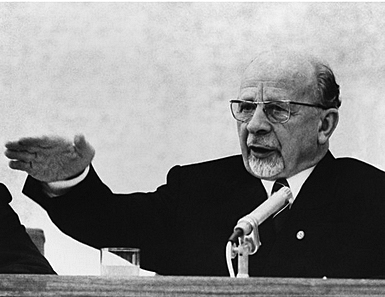

Perhaps the most intriguing portion of this book is the plot that Khrushchev successfully instigated and how it was carried out against Beria. Stalin’s first Lieutenant had greatly underestimated Khrushchev, the former Ukrainian operative who fairly recently had been brought to Moscow by Stalin, and as the current head of the Secretariat had become Beria’s chief opponent in the Kremlin power struggle.

Khrushchev had persuaded Malenkov, Molotov, and Bulganin to take an active role in the coup, while Kaganovich, Voroshilov, Kaganovich, and Mikoyan assumed more passive roles, believing it to be more politically expedient not to interfere until the coup had been carried out.

Beria was arrested by military men at a hastily convened meeting of the Presidium on June 23, 1953, only nine days after the East German insurrection was squelched by Russian troops. Khrushchev had been moving feverishly within the Politburo and the military to undermine and gather forces against Beria, who was uncharacteristically caught off guard and entered the Presidium without suspecting the plot and the coup that awaited him. Once inside the Presidium, MVD guards (security apparatus successors to the NKVD) posted outside were dismissed by Defense Minister Bulganin and replaced with military troops loyal to General K. S. Moskalenko and Soviet Marshall Georgi Zhukov, who had been brought into the plot. Beria’s fate was sealed.

Beria was arrested by the generals, while he was being lambasted by his former comrades. Leonid Brezhnev came prepared hiding a pistol, but most members of the Politburo were not privy to the plot yet they quickly fell into line. After Beria’s arrest, Khrushchev moved swiftly and began arresting Beria’s closest associates and purging the upper echelons of the MVD. Most of the top MVD officers remained loyal to Beria and were later executed. The only high ranking MVD officers to desert Beria immediately after his arrest were Sergei Kruglov and Ivan Serov, who were not considered part of the “Georgia Gang.” For their acquiescence in the affair, Khrushchev later promoted them.

The Central Committee secret proceedings from July 2-7, 1953 remained locked in the Russian archives until 1991. Knight writes: “It provides a fascinating and revealing picture of the events surrounding Beria’s arrest, making it clear that Beria’s opponents were still on very shaky ground at this point and were thus ‘pulling out all the stops’ to contrive a criminal case against Beria and persuade Central Committee members that they had done the right thing.”

The trials of Beria and his lieutenants were conducted in camera, in secret from December 18-23, 1953. To this day, controversy exists as to whether Beria participated in the proceedings or had already been executed along with his comrades by the time of the trial, six months after their arrest. Among the many charges levied against them, they were accused of attempting “to seize power and liquidate the Soviet worker-peasant system for the purpose of restoring capitalism and the domination of the bourgeoisie.”

Incidentally, Khrushchev adopted many of Beria’s policies, including de-Stalinization, despite opposition from the Soviet nomenklatura. But as Knight comments, “Khrushchev was incapable of making substantial reforms because he was too deeply cast in the Stalinist mold…he too adopted the highly personalized capricious and autocratic style of the Soviet leadership since the Stalinist period.”

Khrushchev willingly carried out the collectivization and general repressive measures including bloody purges in 1937-1938. Like Stalin’s other lieutenants, his hands were drenched with Ukrainian and Russian blood. Beria’s life in contrast to Stalin’s other sycophantic lieutenants can be summarized by the author’s following words: “If Beria was an exception, it was not because he was amoral, sadistic, and cruel. Rather it was because he was intelligent, astute, and devoted to achieving power. He was also adept at the kind of court politics that prevailed in the Kremlin and below. His deviousness and two-faced behavior was an asset in this environment, particularly in dealing with Stalin. Beria never ceased to maintain his flattering tone — ‘As usual, you have hit the nail on the head, Josif Vissarionovich’ — though by the end he was heaping scorn on Stalin behind his back.”

This book is highly recommended and deserves a 5-star rating.

Reviewed by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria, Jr. is a former Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine; Former member Editorial Board of Surgical Neurology (2004-2010); Member Editorial Board of Surgical Neurology International (2011-present); Recipient of the Americanism Medal from the Nathaniel Macon Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) 1998; Ex member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002-05; Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002); Editor Emeritus, the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS); Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002).

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Book Review: Beria — Stalin’s First Lieutenant by Amy Knight. HaciendaPublishing.com, December 23, 2011. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/book-review-beria–stalins-first-lieutenant-by-amy-knight

Copyright ©2011 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., MD