- Articles

Bastille Day And The French Revolution (Part III): The Denouement

Note: The article that follows is part of a series written years ago that served as a springboard for expansion on the French Revolution section of Dr. Faria’s book, Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions published in December 2024 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. The articles were fully expanded, revised, and updated for the chapters in that book, which is frankly much improved from the original articles. — Editor. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-0364-1560-0

We have seen that the French Revolution did not give the French people a true constitutional republic extending to its citizens the natural rights of man to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. The French Revolution wanted to go beyond that and create a utopia of happiness, misunderstanding liberty and adding fraternity and equality to the brew. Forced fraternity and equality were proven to be and remain mutually exclusive from individual liberty. While our American republic respected the rule of law and protected the basic concepts of individual rights and freedom — namely, life, liberty, property and the pursuit of happiness — the French Revolution established mob rule followed by dictatorship. It showed the world and put into practice the scissor strategy of forcing radical change upon society using fear and ultimately, terror as its basis — a methodology that Karl Marx later expounded into dialetical materialism and communism. That philosophy, Marxism, would cost an excess of 100 million people their lives in the tainted 20th century.

The French Revolution had the least amount of success implementing the wealth redistribution policies of some of its adherents. Neither fraternity, liberty, nor economic equality were achieved. Terror was established on all fronts. While the state did confiscate property of the enemies of the revolution, Robespierre and his Jacobins kept such property that was salvaged in the hands of the government, and the rank and file revolutionists had to keep an inventory of such appropriated goods and properties. In a way, this firm, strict accounting of expropriated property (i.e., that was not stolen or destroyed) was helpful in keeping the mob from looting, overrunning and turning France into a wasteland. Robespierre disdained material wealth. Poverty to him was synonymous with virtue. The Incorruptible worshipped not on the altar of wealth and indulgence, but on the stone of abstract altruism, abstinence, and personal power. The fall of Danton was predicated, in part, by the economic and financial misdeeds of some of his close friends such as Chabot and Fabre d’ Eglantine. For this association and Dantons calls for economic freedom, Robespierre called his former friend and colleague a “rotten idol” and sent him to the guillotine.

Francois Babeuf, a political activist, was one, if not the first, modern communist.* He espoused collectivism, agrarian reform and economic equality during the French Revolution, but his ideas never took complete hold with the leadership of the Jacobins.

According to David P. Jordan in his book, The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre (1985), a virtual apologia of the Incorruptible, both Saint-Just and Robespierre believed the state had a role to play in providing for “minimal subsistence” to the people. This was “the debt of the rich to the people.” Buissart, an old friend of Robespierre from Arras, wrote that the people “were dying of hunger in the midst of abundance. I believe it is necessary to kill the mercantile aristrocracy just as we killed that of the priests and nobles.”

Robespierre never went as far as that, although he threatened and admonished “the rich egoist may share the fate of the nobles and the King if they continue to behave like them.”

In the summer of 1793, the National Convention, in an effort to ease the worsening economic situation, went so far as to institute wage and price controls as well as regulation of the grain market. The Assembly imposed a ceiling on the price of grain and other grocery items, what amounted to an economic terror. Girondin leader Charles Barbaroux, already a marked man by the Hébertists, nevertheless spoke in opposition. He complained that the ceiling would exacerbate the problem of supply and demand and aggravate the scarcities. Barbaroux also predicted inflation because of the devaluation of the currency and loose fiscal policy. Every prediction he made came to pass.

Vergniaud, the golden-tongued orator and Girondin leader, and Danton opposed these extreme economic measures. Nevertheless, that summer, the Convention implemented price ceilings, maximum wages, relief for the poor via obligatory loans, and exorbitant taxes on the rich and forced acceptance of fiat currency, assignats. Jacques Roux addressed the Convention on June 25, 1793 and accused the new “commercial aristocracy” of being “more terrible than the [old] nobility.” He called for the crushing of the rich in France.

On July 26, the death penalty was passed for hoarders of grain and “blood-sucker” currency speculators. The armées révolutionnaires were empowered to snoop around the towns and countryside to look for hoarders and speculators. They enforced the economic Terror by ransacking villages and terrorizing rural communities. The monetary policy failed and the deprecated assignats were demonized with the creation of a black market for hard currency. The economic Terror was truly underway by the fall of 1793.

The Ventose Decrees (February 26, March 3, 1794) proposed by Robespierre’s most trusted lieutenant Saint-Just, provided that the State should confiscate émigré property and distribute it to the needy. Saint-Just and other Jacobins argued that the enemies of the revolution had no civil rights and their property should be confiscated. Robespierre, although supportive of these decrees, never felt he had the support of even the most hardline Jacobins to implement these decrees. These decrees died without enactment.

Earlier, Pierre Chaumette, leader of the Paris Commune, had also militated and demanded that the National Convention authorize the government to confiscate private property and distribute it to the “people.” He had the support of Hanriot, commander of the National Guard, and Pache, the mayor of Paris. Nevertheless, the ruling Jacobins in the National Convention, by this time in control of the sans-culottes army, also rejected this demand, to the chagrin of René Hébert and his ultra-radical followers.

Just before the denouement of 9 Thermidor, Barère had tried to reach a compromise with Saint-Just and Couthon. He would steer through the legislature the Ventrose Decrees, if only Robespierre would stop hurting Deputies in his quest for virtue. Robespierre refused to compromise. In his speech on 8 Thermidor, he would continue to exterminate the wayward Deputies and enemies of the revolution in his quest to build his Republic of Virtue.

By the spring of 1794, the valiant Girondins, Danton, and his friends Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, and even the sanguinary René Hébert — had all been guillotined. The right side of the Convention stood empty; the center, “the Plain,” remained silent, cowed and stupefied; even the radical Jacobins on the left, the Montagnards, were beginning to fear for their lives. The far ends of the political spectrum, like an excessively bent horseshoe, representing the extremes of anarchy (right) and tyranny (left), became separated by a narrow gap, that of anarcho-tyranny, which agent provocateurs, immorality, and chaos had bridged with the establishment of Robespierre’s stern dictatorship.

As the Deputies trembled in fear, and Paris became deserted and terrorized, one man relatively unknown in history senses his own life is in mortal danger. He exhorts and finally convinces his fellow Deputies to act both decisively and swiftly in order to save their lives.

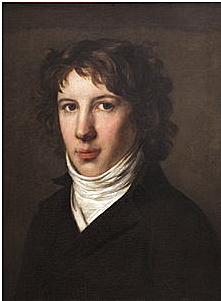

The rallying figure, Joseph Fouché, is relatively obscure in the annals of history, although the details of his life are well known. He was no saint; as a Jacobin, he was ruthless. He committed atrocities as a représentant-en-mission in Lyons in the early part of the Terror. But at the moment of truth, a fearless determined personality was needed to end the Terror that Robespierre had just recently escalated and did not want to end. Fouché conspired and bred intrigue in the shadows, rallying the conspirators, a motley crew, Vadier, Tallien, Barras, and even the sanguinary Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’ Herbois, both in the Committee of Public Safety. The final showdown would take place in the convention, all or nothing, against Robespierre and his allies.

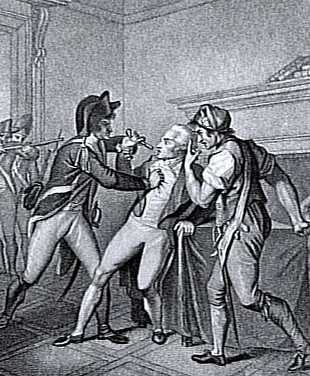

And on 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794), the unthinkable finally happened at high noon. At the Convention, Robespierre was not allowed to speak. Vainly he rose to speak at the rostrum, but a group of conspirators prevented him from speaking. When he reached the podium, his eloquence uncharacteristically failed him. “The blood of Danton is choking you,” yelled a conspirator. When Robespierre was finally able to speak, he could only utter, “For the last time, will you, let me be heard, President of Assassins!” But, it was of no use. The spell of terror and intimidation had been broken by a group of desperate but, ultimately, courageous men who acted as cornered animals, finally assisted by an embolden Convention. Vive la convention! They cried in unison.

The fall of Robespierre, brought an end to the Terror. Robespierre and his henchmen, his brother Augustin, St. Just, Couthon and Hanriot went to the guillotine. Le Bas shot himself to death at the Hôtel de Ville. Robespierre and those closely associated with him in his Committee of Public Safety dictatorship had come tumbling down to a gruesome end.

It was only after the fall of Robespierre and the Thermidorean Reaction that the French revolutionists, the Thermidoreans and the Directory, instituted laissez faire capitalism. Although the political situation was by no means stable, the government welcomed new businesses and entrepreneurship from 1794-1799. Nevertheless, it all ended with the coup of 19th Brumaire and the ascendancy of Napoleon Bonaparte. The revolution was then formally and quietly ended by a decree of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. The political cycle was nearly complete. The French Revolution that had brought about the chaos of mobocracy, anarchy, and tyranny had ended in dictatorship and empire.

Read Part I and Part II of this article.

Footnote

* Francois Babeuf (1760-1797) founded his journal in 1794 and founded the Conspiracy of Equals in 1795, to overthrow the ruling Directory and establish virtual communism in France. In 1797, he was arrested, tried, and executed for leading a plot to overthrow the government.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria, M.D. is editor emeritus of the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons (formerly the Medical Sentinel) and author of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His books are available at https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Bastille Day And The French Revolution (Part III): The Denouement. HaciendaPublishing.com, September 22, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/bastille-day-and-the-french-revolution-part-iii-the-denouement

Copyright ©2021 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.