- Articles

Bastille Day And The French Revolution (Part II): Maximilien Robespierre — The Incorruptible

Note: The article that follows is part of a series written years ago that served as a springboard for expansion on the French Revolution section of Dr. Faria’s book, Contrasting Ideals and Ends in the American and French Revolutions published in December 2024 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. The articles were fully expanded, revised, and updated for the chapters in that book, which is frankly much improved from the original articles. — Editor. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-0364-1560-0

The Incorruptible, Maximilien Robespierre, the Voice of Reason, did not give the French people a Republic of Virtue but a bloody reign of terror incited by mob rule, and the descent into barbarism with the mass killings of men, women, and children by their own government, not because of their deeds or misdeeds, or any real crimes, but because of their birth, opinions, and associations — or simply, for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

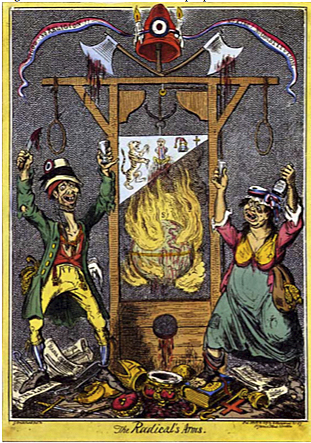

The guillotine was kept busy during the Terror, and when it was not fast enough cutting commoner and aristocratic heads, other grisly methods were used, such as burning, hacking, stabbing, shootings, even cannonades. In the city of Nantes, the sanguinary Carrier instituted the brutal “republican marriages” whereby naked men and women were tied together and thrown into the Loire River. Others were simply tied to barges that were scuttled with resultant mass drownings, the infamous noyades.

At the time of the King’s Trial, many deputies spoke, acted, and voted in fear of their lives (even Danton alluded to this, “it’s our heads or theirs,” according to author, Stanley Loomis), after all, they were deliberating in the belly of the Revolution, in the midst of Paris, surrounded by the ever threatening radical mobs. Many, perhaps most, deputies who were from “The Plain” and voted for regicide did so in fear of and to protect their own lives (it’s the King’s head or my own!), and not because of the persuasive skills of the sanguinary figures, Robespierre and Saint-Just. The Deputies spoke, debated, and voted in fear of their lives in the various people’s assemblies up to the National Convention, fearing the Parisian mobs (and in the summer and fall of 1792 also of the dreaded federe, who inspired the revolutionary hymn Le Marseillaise) and their incitement by the various radical leaders such as Marat and later Hébert, as well as Danton and Robespierre.

Despite Robespierre’s incessant reference to the virtue of the people, he only trusted the people as an abstract concept, like democracy, when the mob’s passion could be rallied to serve the purposes of the revolution. The mob’s violence was justified in the eyes of Robespierre when it answered his own personal call to carry out political riots and revolutionary insurrections. Jacobins, like Robespierre, harangued the convention from above, while the mob intimidated the convention from below to force it to move radically to the far left of the political and social spectrum. This is the very effective political/revolutionary scissors strategy of applying simultaneous pressure from above and below to attain radical change at work predating Hegelian dialectics (dialectical idealism), Marx’s dialectical materialism, and Gramsci’s revolutionary theories for the overturning of society.

Indeed, we have seen the scissors strategy of applying pressure from above and below when the bloodthirsty mobs of the French Revolution, the sans culottes, and the Paris Commune intimidated the National Assembly and the Legislative Assembly with their swords and pikes, marching outside the Convention at the Tuileries demanding change in “government” policy or pleading for the blood of their enemies, while the leaders of the Jacobin Club serving as Deputies clubbed the Convention from within, haranguing the assembly from the speaker’s podium, calling for slightly less of but essentially the same changes as the mob in the name of the people.

Robespierre recognized this fact and throughout the period of 1789-1793, aligned himself with the most vociferous and violent, minority of the elected “representatives of the people.” Later, after assuming effective control of the Committee of Public Safety and his dictatorship was operational, Robespierre came, particularly in late 1793 and 1794, to no longer have any use for the mobs, and then his references to the people became a complete abstraction.

Between 1792-1794, The Incorruptible was instrumental in setting the stage for, and then presided over, the Reign of Terror. His technique was simple but time-tested — namely, the Machiavellian tactic of divide et impera (“divide and conquer”). And, he did so with gruesome efficiency eliminating one by one his divided opposition — i.e., first the monarchists followed by the Feuillants; then Girondins; then the Hébertists; then the Dantonists, its leader Camille Desmoulins and their followers; and finally then anyone who stood in the his way and the continuation of the Terror. Robespierre had succeeded in establishing institutionalized terror as an instrument of State power. He presided over it and used it against his enemies. For him, the end justified the means.

Robespierre sought to create a heaven on earth with himself as high priest, as became evident to many revolutionaries, on the occasion of the Festival of the Supreme Being (June 8, 1794; 20 Prairial). The reality is that while imbibing of this display of virtue and reason, he was accelerating the already rapid action of the guillotine. The Law of Suspects, which had been in effect since Sept. 1793, provided that those persons who by conduct or language were “enemies of liberty” were suspect and liable for immediate arrest. Sharpening the efficiency of the revolutionary tribunals to unimaginable levels of tyranny, the law of 22 Prairial eliminated the rules of evidence and the right of legal defense of suspects. Thus, in the six weeks preceding the Thermidorean Reaction (July 27, 1794), Robespierre had set the stage for institutionalized, legal mass murder, and 1376 victims were executed at the Place du Trône alone by the guillotine.

Before that, of course, the young, idealistic Girondins had been executed en masse with concocted evidence that everyone knew was penned by Robespierre’s young friend, Camille Desmoulin. Later Camille cried when he realized his bearing false witness would send his former friends and colleagues, now political enemies, to the guillotine. The heads of 22 brave Girondin leaders, including Madame Roland, Vergniaud and Brissot rolled. Maximilien Robespierre, the ultimate hero (or anti-hero) of the French Revolution, a national event still magnificently celebrated today in France, believed in and defended the institution of mass murder in the name of the revolution. The country lawyer from Arras was totally devoid of mercy, even when it came to sending revolutionary heroes and former friends to the guillotine.

L’Incorruptible thus sent Camille, his protégé, now a friend of Danton and the man who led the attack on the Bastille on July 14, 1789, to the guillotine. A few days later Camille’s wife, Lucile followed him to the scaffold. She had pleaded with Robespierre to save her husband’s life in the name of their infant son, Horace, to whom Robespierre was godfather — but to no avail.

Robespierre also sent the “Titan of the Revolution,” Georges Danton — the man who had transformed the Paris Commune into the Insurrectionary Commune(i.e., in preparation for the storming of the Tuileries), the man who had inspired the Miracle of Valmy, and the revolution’s greatest orator and hero — to the guillotine. Danton had finally come to his senses and had tried to stop the Terror. He also pleaded, along with Camille Desmoulins, to end the excesses of the revolution and to free 73 Girondin Deputies held in prison among the 150 representatives of former assemblies or of the sitting National Convention. Robespierre, implacable as ever, refused to ease the Terror. The Incorruptible, thought he was in firm control of the Committee of Public Safety and the Revolutionary Tribunals and held all the cards. Hébert and his friends had already “been shaved by the national razor.” Camille and Danton and their friends had followed that same spring of 1794. General Westermann, one of the military leaders of the storming of the Tuileries and the overthrow of the monarchy, August 10, 1793, voluntarily joined his friends and went with the Dantonists to receive the cold blade of the guillotine.

And yet, Robespierre tried to dissociate himself as much as possible from those decisions that could later incriminate him. When he signed Danton’s death warrant, which had to be signed by the members of the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security, he scribbled his signature in very small letters towards the corner and in between two other signatures, as furtively as possible, trying to escape responsibility for his action. Vacillation and acting stealthily against his enemies were two of Robespierre’s modus operandi.

With these tactics, Robespierre nearly succeeded in having others do his dirty work while working stealthily against his divided enemies — all the while trying to avoid responsibility. He never frontally attacked his enemies unless assured of victory. But, in the end, all of these precautions were of no use; it all collapsed when the erstwhile calls for Vive la République! Vive Robespierre became “Down with the Tyrant!” (Execution of Robespierre, above) But I am getting ahead of myself.

In his book, Robespierre: The Fool as Revolutionary, Otto Scott writes, “Robespierre simply died, but folly has a virulence that outlasts its inventor. He inspired more communes, more voices of virtue, more Lenins, and Castros and Maos, more murder and hatred, more death and misery, than any other of the Sacred Fools that have emerged to plague honest men.”

The scissors strategy of having seemingly desperate forces acting together towards a common subversive goal and to force destructive change was assimilated as dialectics by Karl Marx in his Communist Manifesto. It was learned well and followed by communists in the consolidation of power in their totalitarian regimes. We have seen this methodology followed in the 20th century in varied forms in Red China, the former Soviet Union, Cuba, and other former Soviet satellites during the Cold war.

In the Paris Jacobin Club from 1791-1793, Maximilien Robespierre developed the methods of public self-criticism, “purifying scrutiny” as he called it, which preceded purges of individuals and which amounted to their death warrants. Mass arrests and executions followed these purges. This methodology of mass purges were later emulated and surpassed by totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, particularly Joseph Stalin’s. To facilitate the arrest and apprehension of political opponents, 20th century tyrants also followed the lead of the French revolutionists. They also established neighborhood committees (for public surveillance), revolutionary tribunals (for the administration of swift “people’s” justice), and mass executions. The radical journals and pamphlets together with the publication of the most radical speeches delivered at the revolutionary clubs paved the way for manipulation of the press, the application of mass psychology for State indoctrination, etc.

As a guiding light, the revolutionists had stated that “all is permitted to those who act in the revolutionary direction.” Using similar language shortly after the triumph of his revolution, the 20th century dictator, Fidel Castro, would admonish Cuban writers and intellectuals, “With the Revolution everything, against the Revolution, nothing.” At the time, he was already instituting neighborhood committees and administering people’s justice to consolidate his power.

In Part III of this essay, “The Denouement,” we will conclude our discussion of Bastille Day and the French Revolution and its aftermath.

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D., is an Associate Editor-in-Chief and a World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI); Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He served under President George W. Bush as member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2002-05); Realclearhistory Author (2012-present); Founder & Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002); Editor Emeritus; Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Bastille Day and the French Revolution (Part II): Maximilien Robespierre —The Incorruptible. NewsMax.com, July 21, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/bastille-day-and-the-french-revolution-part-ii-maximilien-robespierre–the-incorruptible

Copyright ©2015 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.