- Articles

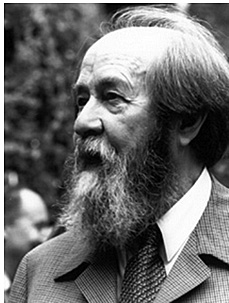

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — Towering figure of the 20th century and his enduring legacy of freedom!

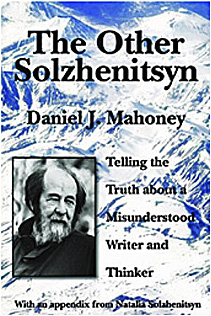

A book review of The Other Solzhenitsyn: Telling the Truth about a Misunderstood Writer and Thinker by Daniel J. Mahoney (2014)

I agree with the tenets of this important book on the life and philosophy of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, an insightful intellectual profile as recounted by the author Daniel J. Mahoney, a political scientist at Assumption College. Mahoney has in fact written a masterful semi-biographical and inspirational tome on the legacy of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, a legacy of the pursuit of truth, physical and moral courage, literary genius, and man’s insatiable thirst for freedom.

Solzhenitsyn was a towering figure in the 20th century, not only for his unique contribution in exposing the immorality of the communist system, in system and militating the collapse of the “Evil Empire” of the Soviet Union, but also as a political philosopher, memoirist, and historical novelist of the highest order. All of this is recounted eloquently in this book, particularly Solzhenitsyn’s more controversial legacy in the Russia of Vladimir Putin.

As recounted in previous articles, there is no question Solzhenitsyn received superlative accolades early on his career after the publication in the Soviet literary magazine Nova Mir of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962). The little novel was even used by Nikita Khrushchev to further dismantle Stalin’s cult of personality. With Khrushchev’s imprimatur, Western liberals had no qualms about embracing Solzhenitsyn at a distance. Later, in the days of Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov (in the KGB), the fame he attained from the little novel protected Solzhenitsyn’s life, at least in part, from the that continued to threaten and harass him.

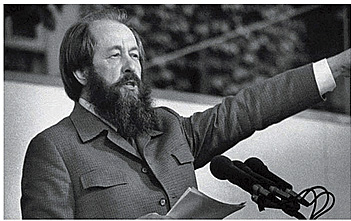

But the truth is Solzhenitsyn’s adoration by the Western, particularly American, intelligentsia ended quickly after he was exiled from the USSR, more precisely after he gave the 1978 commencement address at Harvard University. He would not be forgiven by the Western liberals, who decried his conservatism when he denounced Western decadence, moral relativism, and even lambasted the anti-war protesters who forced the withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Vietnam, resulting in the communist takeover of that country. Solzhenitsyn still has not been forgiven for these sins by liberals in the West. But it’s fortunate that at least in Russia, a nation that experienced the collectivist evil firsthand, he has not been forgotten. Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago (1973), is now required reading in Putin’s Russia. And Solzhenitsyn’s legacy of freedom and resistance to tyranny is seen by moderates in the Russian Federation as a bulwark against the return of communism.

Liberals in the West abandoned Solzhenitsyn as soon as they found out he was not one of them, a secular humanist liberal. However, more lasting praise for the Russian giant (both in intellect and physical stature) has come from more conservative sources in the West: Former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union (1952) George Kennan, the architect of Truman’s policy of communist containment in the late 1940s, called Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, “the greatest and most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be leveled in modern times.” Kennan has never spoken more clearly or better. National Review editor William F. Buckley Jr. described Solzhenitsyn as a man of “moral splendor” and “the outstanding figure of the century.” Even , a New York Times journalist and an admirer of Lenin and , reportedly admitted that Solzhenitsyn was “a worthy successor to Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov, Bunin, and Pasternak.” But, for the most part since the time of his Harvard address, Solzhenitsyn has been maligned, criticized, or simply ignored by the liberal Western intelligentsia. This is one reason Mahoney’s book was needed; it supplements Michael Scammell’s 1984 authoritative biography entitled Solzhenitsyn. are needed of course to combat the apathy and ignorance of the times as it concerns the life and career of a man worthy of remembrance not only for his legacy in the cause of freedom, but also for his literary bequest in the cause of literature. Solzhenitsyn’s own struggle for freedom of thought and expression is recounted in his memoirs, .

Mahoney defends Solzhenitsyn against his liberal critics and points out that despite the Russian’s criticisms of the West, he by in large admired the Western intellectual tradition, citing for example, Solzhenitsyn’s 1993 address to the International Academy for Philosophy in Liechtenstein, where he lavishly recognized Western freedom and the “historically unique stability of civic life under the rule of law—a hard-won stability which grants independence and space to every citizen.”

Solzhenitsyn’s autobiography, The Oak and the Calf; his two installments or “Knots” of The Red Wheel, his series of historical novels about events leading to the 1917 Russian Revolution (e.g., “August 1914” and “November 1916”); along with The Gulag Archipelago are perhaps the greatest of his literary achievements. And yet, the third installment of The Red Wheel series, “March 1917” — dealing with the events that led to the February Revolution (which actually toppled Tsar Nicolas II and temporarily empowered the moderate revolutionaries led by Alexander Kerensky) and the subsequent more tragic events that ushered in the October Revolution and the military coup by — has yet to be translated into English.

Like Mahoney, I have read all of Solzhenitsyn’s works that have been translated into English or Spanish and have found them to be genuine literary masterpieces. At least on this count Salisbury was totally correct. I have been waiting eagerly for the translation of the third installment, but it has only been available in Russian and French until now.

But there is light at the end of the tunnel, I have just read a review of Mahoney’s book by Brian Anderson in realclearhistory.com in which Anderson states that the Kennan Institute recently announced its plan to translate the remaining volumes of The Red Wheel by the centenary of Solzhenitsyn’s birth in 2018. This was music to my ears and it gladdened my heart!

As recounted in The Other Solzhenitsyn by Daniel J. Mahoney and Solzhenitsyn’s own The Gulag Archipelago — no one has suffered oppression and survived against all odds; resisted and confronted evil, an evil exercising nearly complete omnipotence against the individual; then defeated the totalitarian evil so thoroughly that it crumbled into dust; and in the end, lived to see himself vindicated and triumphant — as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn experienced!

The Other Solzhenitsyn is a must-read book for anyone interested in the legacy of this towering figure of history and those who relish inspirational works surrounding the legacies of great and courageous historical figures. Additionally, I would recommend reading Solzhenitsyn’s own works, at least those mentioned here. They will enrich your existence, give you a new sense of appreciation for life in freedom, and will expand your literary horizons beyond the constraining limitations of contemporary literature and vacuity of popular culture.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr., M.D. is Associate Editor in Chief and World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International. He is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is: HaciendaPublishing.com.

Copyright ©2015 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.

The Other Solzhenitsyn by Daniel J. Mahoney. South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine’s Press, 2014, 256 pages.

The article can be cited as: Faria MA. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — Towering figure of the 20th century and his enduring legacy of freedom! HaciendaPublishing.com, February 4, 2015. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/aleksandr-solzhenitsyn-towering-figure-of-the-20th-century-and-his-enduring-legacy-of-freedom/

The photographs used to illustrate this book review came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Mahoney’s The Other Solzhenitsyn. This book review was first published in HaciendaPublishing.com on February 4, 2015.

3 thoughts on “Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — Towering figure of the 20th century and his enduring legacy of freedom!”

The KGB arrested people in the middle of the night but… with a knock on the door. Yet here is Alexandr Solzhenitsyn discussing it:

“… That’s what arrest is: it’s a blinding flash and a blow which shifts the present instantly into the past and the impossible into omnipotent actuality. That’s all. And neither for the first hour nor for the first day will you be able to grasp anything else.

Except that in your desperation the fake circus moon will blink at you: “It’s a mistake! They’ll set things right!”

And everything which is by now comprised in the traditional, even literary, image of an arrest will pile up and take shape, not in your own disordered memory, but in what your family and your neighbors in your apartment remember: The sharp nighttime ring or the rude knock at the door.

The insolent entrance of the unwiped jackboots of the unsleeping State Security operatives. The frightened and cowed civilian witness at their backs. (And what function does this civilian witness serve? The victim doesn’t even dare think about it and the operatives don’t remember, but that’s what the regulations call for, and so he has to sit there all night long and sign in the morning. For the witness, jerked from his bed, it is torture too—to go out night after night to help arrest his own neighbors and acquaintances.” ― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918–1956 More from my hero in another post later… Dr. Miguel Faria

“And how we burned in the camps later, thinking: What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say good-bye to his family? Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand?… The Organs would very quickly have suffered a shortage of officers and transport and, notwithstanding all of Stalin’s thirst, the cursed machine would have ground to a halt! If…if…We didn’t love freedom enough. And even more – we had no awareness of the real situation…. We purely and simply deserved everything that happened afterward.”― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

News —08/05/2008 08:59:24 EST

MISHA JAPARIDZE/AP Photo

Russians pay tribute to Solzhenitsyn

By DOUGLAS BIRCH, Associated Press Writer

Hundreds of Russians lined up in the pelting rain on Tuesday to pay tribute to Alexander Solzhenitsyn as the author, dissident and patriot lay in state inside the Russian Academy of Sciences. A military honor guard stood next to Solzhenitsyn’s open casket, located in a cavernous hall at the academy, as mourners filed by and placed long-stemmed flowers at the foot of the bier. The ceremony had many of the trappings of a state funeral.

Solzhenitsyn’s wife Natalia struggled to contain tears as she stood watch over her husband’s coffin with her sons, as mourners offered condolences. At one point, she bent at the coffin and kissed its edge. Solzhenitsyn – who died Sunday at the age of 89 from a chronic heart condition at his home outside Moscow – is to be buried at the Russian capital’s Donskoi Monastery on Wednesday.

For Russians today, Solzhenitsyn is a stern figure from an age gone by, a man whose legacy was as thorny and complicated as his personality. Solzhenitsyn’s nonfiction trilogy, “The Gulag Archipelago,” published in the 1970s, shocked the Soviet elite, helped destroy lingering support for the Soviet experiment in the West and inspired a generation of dissidents inside the Soviet Union.

The response to Solzhenitsyn’s death was muted here. The author, who spent 20 years of exile in the West following his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974, evoked little sympathy among those with fond memories of the Communist era. Solzhenitsyn had also estranged himself from liberal reformers with his embrace of former President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to roll back democratic reforms in Russia.