- Articles

A history of medicine from a secular humanist perspective!

A book review of The Story of Medicine by Victor Robinson, MD.

Dr. Victor Robinson was Professor of History of Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia.[1] Because the history of medicine has been neglected for decades, this specialty will no longer be found listed among the faculty or the subject of any medical school curriculum. This is a deficiency that the late scholar Plinio Prioreschi, M.D., PhD, lamented in the first three volumes of his monumental A History of Medicine, and I cannot help mentioning it too.[2,3,4] Medical history is medicine and medical ethics and should continue to be a subject of study and research for future physicians. If they don’t know where they come from, how do the young doctors know where they are going or are being led by others?

As it happens, Robinson quotes the historian Thucydides in the subject of general history. Thucydides is quoted as saying:

So adverse to taking pains are most men in the search for the truth and so prone are they to turn to what lies ready at hand. And it may well be that the absence of the fabulous from my narrative will seem less pleasing to the ear; but whoever shall wish to have a clear view both of the events which have happened and of those which will some day, in all human probability, happen again in the same or a similar way — for these to adjudge my history profitable will be enough for me.[5]

I beg the reader’s pardon for this early digression, returning to The Story of Medicine by Professor Victor Robinson, the book is well-entitled because this history is recounted as if by a raconteur, a medical storyteller rather than by a historian. It is well told, which is why this book is well-liked and cited frequently in the medical history literature. The book contains 13 chapters beginning with the Stone Age and ending with Medicine and Sociology in the America of the 1920s.[1]

Many witty anecdotes are related in this book. One of my favorites occurs in Chapter 2, “Greek Medicine in Alexandria.” The Great Herophilus (335–280 BC), Father of anatomy, worked in the Alexandrian Museum under Ptolemy Philadelphus (king of Egypt; 285–246 BC) solving such anatomical problems as discovering the torcular Herophili (“wine press of Herophilus”) and the calamus scriptorius of the fourth ventricle. But the furor of the day and what was troubling and confounding the great men of Alexandria was the problems in logic created by the sophistry of the Greek sceptic philosophers, such as Diodorus Cronus of Megara. After recounting one of the troubling syllogisms, Robinson writes, “Equally provocative of sleepless nights was another quibble of Diodorus on the non-existence of motion: ‘if a body moves, either it moves from a place where it is, or from a place where it is not; but it does not move from the place where it is, because it would not be there… Therefore nothing moves.’ “[5]

Philosophers are subject to the afflictions and accidents of mankind, and so it happened with Diodorus, who dislocated his arm. The best physician was summed. Herophilus arrived and pondered the problem. He turned to Diodorus and said: “According to your principles it could not have moved from one or the other place. Therefore it has not moved.” Robinson writes, “A philosopher in pain ceases to be a philosopher, and Diodorus begged for surgical instead of dialectic treatment.”[6]

Unfortunately, this book has its own detractions. I will not dwell on the difference in interpretation on medical history, but I would be remiss if I did not mention several instances in which I find fault with this author. One has to do with Chapter 3, “Greek Medicine in Rome.”[7] Rome, Roman culture and Romans in general are depicted in the worst possible light. Robinson obviously has a prejudicial view of Roman civilization and cannot prevent his bias from entering into the narrative. This is inexplicable for a professor of medical history, and I must call it as I see it. The worst sides of Cato the Elder, Julius Caesar, even the great historian Tacitus, are presented in their darkest moments. Tacitus himself is thrown on the pile of Romans who were, according to Robinson, “students of sexual perversions and psychopathology.”[7] Rome itself, Robinson trumpeted, is a “brothel with emperor or empress as chief whoremonger. Julius Caesar gave his virginity to King Nicomedes…the bald adulterer — which is why he insisted on wearing the laurel-crown….” Which brings us to the point that this is a book on medical history and not on the debaucheries and sexual perversions of Rome, as tantalizing as that subject may be. It is also not fair to so characterize the great civilization that brought us the marvels of civil engineering, jurisprudence, classical scholarship (e.g. Cicero, Varro, Vitruvius, Pliny, etc.), literature (e.g., Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Juvenal, Lucretrius [the only Roman singled out for praise without caveats], etc.), historians (e.g. Livy, Plutarch, Tacitus, etc.), as well as public health advances, which were not to be surpassed until the 19th century. It was also Roman power that kept the barbarians at bay for centuries until Christianity had half tamed them before the final collapse of Rome in A.D. 476. It is also unfair to the exalted medical figures who practiced Roman medicine, e.g., Celsus, Scribonius Largo, Dioscorides, Asclepiades, Soranus, Galen, etc.

Moreover, this incursion into foreign territory by Robinson brings errors into the narrative.[7] While the peccadillos on emperors, empresses, and Julius Caesar may have been correct in many instances, Robinson makes blanket statements condemning an entire civilization. As to the laurel crown, it is factually incorrect. It was an Oak Crown won by Julius Caesar as a young military commander when he saved a whole Roman legion from utter destruction in a war in Asia Minor. The Oak Crown was awarded to him and by the laws of Sulla, Caesar was to wear it on all public occasions, such as at the Senate, and other civic ceremonies, which for men of his standing were frequent.

This anti-Roman proclivity is also depicted throughout the entire chapter, including medical history itself. For example, Robinson delights in describing the disgusting and inefficient medications (Dreckapotheke) prescribed by the Roman pater familiae for their families, slaves and themselves. It gives the impression that the Dreckapotheke was the invention of the Romans when, in fact, these filthy and disgusting substances were prescribed by physicians in all ancient civilizations, including Greek physicians in the Corpus Hippocraticum.[2-3]

Robinson does not like Galen, the man or the clinician, even when he reluctantly admits the great Pergamum physician is a “giant among dwarfs” and credits him as “the founder of experimental physiology.” Galen is loudly applauded only when he derides and excoriates his physician colleagues for their alleged ignorance, greed, and sycophancy. He also applauds Galen’s diatribes against athletes and physical sports.[8]

Another problem with this author is that he passes judgment on historical figures based on the standards of his own time, and not of the era in question. He passes harsh judgment on Galen because the great physician from Pergamum also subscribes to teleology, which is a major academic sin in the eyes of Robinson, who smells religion at every turn, even from a pagan. At the heart of the matter for Robinson is Galen’s unpardonable sin, same as for Aristotle’s — i.e., the teleological concept of intelligent design and final cause and the belief of these men in the existence of a Creator.[9] As will become evident to the reader this is an unforgivable intellectual sin and anathema to Robinson’s inchoate secular humanism.

In Chapter VI, “Arabian Medicine in the Middle Ages,” despite the title, Robinson takes a Parthian shot at Rome, his first bogeyman, and then enters the realm of early Christian theology and history to take aim at his second bogeyman, or rather punching bad, the Medieval Christian Church. He writes: “Even the crimes of Imperial Rome grow pale in comparison with the amount of human blood that was now shed over myths.”[10]

Robinson then trots to battle, condemns and describes graphically the evils of the Christian Crusades, while forgetting to relate the much more bloody Mohammedan conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, which are largely glossed over. Robinson then anathematizes the three monotheistic religions, but Christianity is always the worst offender, receiving the highest vituperations. Only Buddhism is cited for praise and given credit for peace, compassion and the inception of the first hospitals. Islam is cited positively in this regard, but Christianity is given no credit, cited only for violence, ignorance, and superstition. Animosity then animates Robinson, who belittles the contribution of monks, such as Cassiodorus (c. A.D. 490-580) already copying and preserving the Greek and Latin classics a century earlier in the Benedictine monasteries of the West,[11,14] writes:

From Jundisapur, Greek science spread throughout the Moslem world. When the intellect of Europe was so clouded by monkish fables that the monasteries were buying milk purportedly to come from the breast of the Blessed Virgin, barbarian brown-skinned tent dwellers became the saviors of Greek philosophy.[12]

The attempted amalgamation of Origen between Christianity and the teachings of Plato and Aristotle is described as, “a bridge over which antiquity walked into Medievalism.”[10] Once again rancor befuddles Robinson who forgets that after the fall of Rome in A.D. 476, it was the Dark Ages which followed for nearly 500 years before the Middle Ages can be characterized as Medievalism (A.D. c. 1000-1300). Acrimonious bias against Christianity unfortunately mars this book in many places.

We finally enter the topic at hand in this chapter, and we read sympathetic biographies of the Arabic and Islamic physicians and medical philosophers: Rhazes, Avicenna, Avenzoar, Averroës, and Albucasis, all get good marks. Albucasis hardly gets upbraided for making cautery, the hot iron, the hallmark of Islamic surgery. Averroës, an Islamic dissenter who admired Aristotle and attempted to reconcile the Greek sage to Islamic teachings, gets a hagiography; but Maimonides, a devout Jewish physician and philosopher, gets a bad rap for his attempted reconciliation of Aristotle with Judaism.[13]

All religions are bad enough but some religions and devotions are worse than others, at least in the mind of Robinson, and the intolerance he traces to the three monotheistic religions creeps into his own writings with a vengeance. Particular venom is directed to Christianity. Early in Chapter VII, “European Medicine in the Middle Ages,” Robinson summarizes what we can expect to find in this chapter, and what we also have come to expect from him. We’re not far off the mark. He writes:

It’s a tragic day for Europe when it exchanges the myths of the Greeks for the myths of the Jews. Jupiter smiles in Homer and laughs aloud in Hesiod, but Jehovah of the Jews is a chronic dyspeptic, belching fire and brimstone, threatening and cursing, hating and slaughtering the human race. Intolerance is his keynote, and destruction is the passion of the Lord of eternal vengeance. The gloom of the Scriptures descends upon medievalism.[14]

Thus, Chapter VII is another an eye-opener. Although much of what Robinson writes is true and his conclusions are frequently valid, his intensity and zeal to expose “superstition” often lead him astray. Robinson for example had forgotten that he had excoriated and condemned Rome and her civilization, but now suddenly he realizes that the fall of Rome has caused the curtains of the Dark Ages to fall on the stage of Europe and the “bloodthirsty” Romans are supplanted by the “bloodthirsty” Christians. The fact that Rome kept the barbarians in the West at bay for centuries safeguarding the Mediterranean sea, encouraging trade and commerce, and protecting Greek and Roman civilizations, did not occur to Robinson. The fact that Christianity had partially tamed the barbarian conquerors did not enter his mind. Those facts are not admitted or considered. He sees only the dark side of Rome and Western institutions. The Fall of Rome is only lamented because Christian religion enters the picture in a big way. Instead of accepting the verdict of history that cannot be undone, Robinson now castigates Europe for the inception of mysticism, superstition, pietism, and religion — which now in his mind is a blend of two evil bogeymen: Roman culture and Christianity. Graeco-Roman medicine, he laments, has been substituted for supernaturalistic Christian piety. Only Arabian and Islamic medicine are given all the credit for recovering and preserving Greek naturalistic medicine and the works of Aristotle. Once again Robinson has forgotten that there were two other repositories of learning, the Christian Benedictine monasteries, where monks copied the classics and practiced monastic medicine, and the basilicas in Christian Constantinople, where exegeses were published and the scribes also preserved and copied invaluable manuscripts.[4,11,14]

It is not that Robinson does not mention Constantinople, monastic medicine or Cassiodorus. He does. It is the prejudicial or demeaning way in which they are incorporated into his “Story of Medicine.” Constantinople is not cited for her magnificent Byzantine art and architecture, majestic St. Sophia, or as the bulwark against Bulgar pillagers and Scythian marauders, or as a seat of learning and piety. Constantinople is mentioned in passing almost solely as the victim of the devious Fourth Crusade, where “the rage of Christian against Christian is almost unparalleled in the annals of the human race… where the prostitute dances in the seat of the Patriarch; soldiers of the cross get drunk from the chalices of the church…” and so on.[14] Monastic medicine was “more a matter of calligraphy than scholarship.”[14] And in the Western monasteries, Greek medicine is not preserved but “immured, awaiting resurrection.”[14] Moreover, people purportedly, “protested against the expulsion of women from the monasteries, since these concubines in some measure protect the wives and daughters of the peasantry from monkish lust….” He has more to say on sex and carnal sins in monasteries as well as convents: “Repentant females who entered nunneries were often not permitted by the father confessors to carry out vows of future chastity. The pursuit of licentiousness filtered down from St. Peters chair to the lowest vagrant monks.”[15] Robinson thus gives short shrift to monastic medicine and Cassiodorus’ scholastic and illuminated book works. The exceptions are made the rule so that Robinson’s wicked perspective on Christianity prevails, and Christian morality becomes the incarnation of pure evil with no redeeming qualities for the soul of the Christian faithful.[15] In other words, historic terms and events are used as bully pulpits for his repeated bitter and tendentious attacks, mere punching bags to vent his verbal outrage and impose his interpretation of (medical) history. In this fashion Robinson expresses the same dogmatic and prejudicial bias he decries in others. It is not his erudition or eloquence, but Robinson’s acrimonious zeal and his unrelenting and tendentious vituperations that we find irksome in a book on the history of medicine.

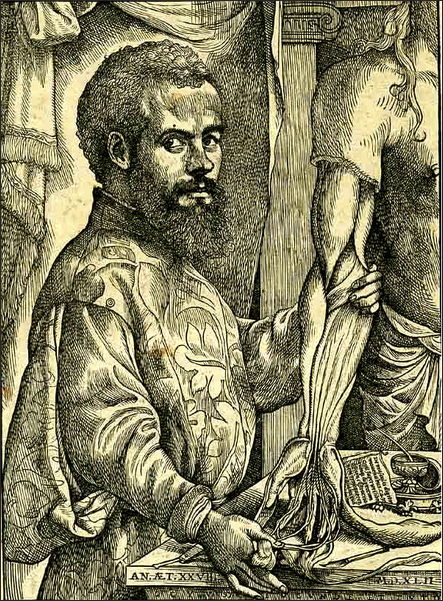

As we have seen Robinson has been belching his own fire and brimstone against sundry malefactors, from Greek medicine in Rome and Roman culture to European Medievalism, so much so that he clouds his own “story of medicine.” Consider his accusation that ancient Roman and later European Medievalism prevented human dissection and the collection of anatomical knowledge essential to medicine and surgery. And the fact that this antipathy to dissecting the human body, to add to Robinson’s ire, occurred despite the “butchery” and “bloodshed” of pagan Romans as well as Medieval churchmen, who had plenty of material, corpses from the carnage, available for anatomical study! Incidentally he inflates his figures for the bloodshed and provides no references. The fact is ancient Egyptians performed millions of embalmings and also did not do any human dissection of the bodies in search of anatomical knowledge; neither did the Mesopotamian or Chinese physicians. And the Greek naturalists, so much praised by Robinson in other matters, themselves did not perform human dissection. The Greeks also refrained from opening cadavers despite their curiosity about nature and the world around them. Other than Aristotle and Galen, who performed systematic animal dissection, there were no anatomists in the ancient world, except for the brief tenure of Herophilus and Erasistratus in Alexandria in the 3rd-4th century B.C., who actually performed human dissection, which was not continued by those who followed. Dr. Plinio Prioreschi has noted that anatomy was of little use to physicians and surgeons in ancient times.[3,4] Even after the great advances in anatomical knowledge and physiology during the Renaissance with Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) and then with William Harvey (1578-1657) — not until the 19th century would scientific and clinical medicine make systematic strides forward, and not until the turn of the century would a seriously ill patient benefit with a greater than 50% chance from consultation with the physician.[2-4]

Chapters VIII, IX, and X deal with medicine during the Renaissance and through the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and describe the medical arts in those epochs,[16] including the thwarted scientific revolutions started with Vesalius and Harvey, revolutions that did contribute bricks to the edifice of science but did not bring about practical advances until the 19th century as mentioned.[2-4]

There is a curious mixture of erudition, arcane knowledge, sometimes wit (Chapter X) punctuated by tediousness, although we are never completely free of vituperation against the ecclesiastical order (Chapter VIII and IX). We are reminded in graphic detail that the 17th century was the age of science as well as intolerance and superstition. Thousands of alleged witches were tortured to death or heinously burned at the stake, their properties confiscated; and although the persecution was widespread throughout Europe, even reaching New England, Protestant Germany was probably the worse.

Chapter X (18th century) is an excellent chapter, elucidating recondite episodes frequently neglected in medical histories. It pokes fun at charlatanism, which takes the full brunt of Robinson’s attack for a change. This chapter is essentially free of ecclesiastical castigation, which is refreshing. The excessive bleeding and purging is referred to as “therapeutic vampirism,” and medical quacks fashioned themselves “venereal specialists.”

Robinson also observes that “charlatans have a flair for exploiting scientific progress,” and the discoveries in magnetism, electricity, hypnotism, etc. of the 18th century, referred to as “the Golden Age of Charlatanism,” was a “Paradise of Quacks.” We are entertained with the stories of such mountebanks as Sir Robert Read, principal oculist to her majesty Queen Anne; the Viennese Franz Mesmer, whose sexual-hypnotist shenanigans were exposed by a commission headed by Ben Franklin and Antoine Lavoisier in Paris; and the Scottish showman, James Graham, who created the “Medico-Magnetic-Musico-Electrical Bed” with the “Goddess of Health” presiding, the ubiquitous Emma Lyon, later Lady Hamilton. Only his premature death before the age of 50 prevented this lascivious quack from extorting £1000 in advance for his “Elixir of Life” from a credulous public.[16]

Those readers who share Robinson’s aversion to major aspects of European culture and Roman civilization in general and to religion and Christianity in particular, will love this book. Some of those on the opposite side may raise their eyebrows and raise objections, as I have done. Those who are less fastidious about these political, ideological and cultural matters, and who thirst for medical history, will find this book helpful, except perhaps for the final chapters — i.e., Chapters XI, XII, and XIII dealing with the Modernization of Medicine, Medicine in America, and Sociology in America — which swung from interesting to tedious, became necessarily out-of-date in describing the present, and made mixed prognostications for the future of medicine. Nevertheless, we must remember Robinson was writing this book in the 1920s (although it was revised in the newer edition in 1943), so that the 19th century was the century of “modernization,” and in the first half of that century we still encountered the epoch of the resurrectionists, when the “body snatchers” plied their trade of robbing graveyards in search of cadavers to sell to the physician-anatomists of the day, particularly in England and Scotland. In fact, we are treated to the crimes of Burke and Hare in gory detail and entertained with the traveling tales of Dr. Charles Edouard Brown-Sequard (1817-1894).

The last two chapters both sing the praises of and deplore American medicine, the state of public health, and the nascent discipline of sociology and social work — not always with justice to the participants or the times in which they live, but always with the fervor of a social moralist possessed with the zeal of righteous indignation. The book, towards the end, enumerates philanthropic voluntary social organizations, calls for more social work, and then paradoxically yearns for the socialized medicine of the future. Robinson forgets the lessons of history that reveal the more government intrusion in social and economic life, the less freedom and the less humanitarianism that comes from the heart and not from positive law and authoritarianism.[11] He ends with: “Preventive medicine, vastly extending the physician’s horizon, is destined to change him from private practitioner to the nobler occupation of a worker for the public health and welfare.”[17] And when that happens, taking care of abstract humanity, who takes care of the flesh and blood, sick, individual patient?

Nevertheless, despite major reservations, this book may be useful to students of medical history. For readers who enjoy Robinson’s style of narrative but without the vituperations, I would also recommend Devils, Drugs and Doctors (1929) and The Doctor in History (reprinted 1989) by Howard W. Haggard (1891-1959). Haggard matches Robinson on eloquence and wit without evoking prejudicial biases and vituperations. And his storytelling abilities are more constant and superior. Those readers with a strong affinity to secular humanism will enjoy this book, as much as those who strongly oppose it will dislike it. For more recent references and scholarly work, I recommend the relatively new, multi-volume classic, A History of Medicine, by Plinio Prioreschi, MD, PhD,[2-4] — works which I am in the process of reviewing, at least the first three volumes. And the short book, A Prelude to Medical History by Felix Martí-Ibáñez (1961), based on lectures to medical students, is also recommended reading as an introduction to this subject.

References

1. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine.The New Home Library, New York; 1943.

2. Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine. Vol. I: Primitive and Ancient Medicine. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995.

3. Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine: Vol. II: Greek Medicine. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1996.

4. Prioreschi P. A History of Medicine: Vol. III: Roman Medicine. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1998.

5. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 47-48.

6. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 70-71.

7. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 86-87.

8. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 127-130.

9. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 131-33.

10. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine.The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 136.

11. Faria MA. Vandals at the Gates of Medicine: Historic Perspectives on the Battle Over Health Care Reform. Macon, GA: Hacienda Publishing, Inc.; 1994, p. 217-254; 267-313.

12. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 134-146.

13. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 146-192.

14. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 196-199.

15. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 214-215.

16. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 238-370. For the clever description of charlatanism, see pages 342-353.

17. Robinson V. The Story of Medicine. The New Home Library, New York; 1943, p. 371-520.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Miguel A. Faria Jr. M.D. is a retired neurosurgeon and the author of the book, Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise (2002) and many articles on science, politics, and medicine. His website is: https://HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. A history of medicine from a secular humanist perspective! HaciendaPublishing.com, March 20, 2015. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/a-history-of-medicine-from-a-secular-humanist-perspective.

(The Story of Medicine by Victor Robinson, M.D. The New Home Library, New York; 1943. Bibliographical Notes, Indexed, 564 pages.)

The photos used to illustrate this book review came from a variety of sources and did not appear in Robinson’s The Story of Medicine, but were added here for the enjoyment of our readers.

Copyright ©2015 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.