- Religion and History

A secular (atheist) philosopher and a layman Christian debate ethics and morality — Part 1 by Wade W. Stooksberry II and Franklin J. Hogue

The following is a dialogue that took place in the comments section in response to a column by Dr. Bill Cummings, a former Catholic priest who writes on religious matters in The Telegraph (Macon, Georgia) from the standpoint of a disavowal of Christian doctrine as stated in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds. It also includes private correspondence and Facebook exchanges between the two debaters.

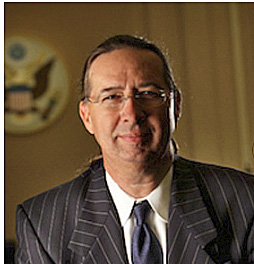

Franklin J. Hogue is a noted Georgia criminal defense attorney with a background in theology and philosophy. He is a follower of pragmatism and a self-avowed atheist.

W. Wade Stooksberry II is a lay Christian apologist, who is one half (with his wife Trena) of the musical duo The DOVES. He has regularly criticized the Telegraph’s Sunday columnist Dr. Bill Cummings for alleged “factual errors and soft hermeneutics” on the Telegraph website and in published letters. His initial post is in reference to Dr. Cummings comments about him On a . The debate extended on and off for several weeks around New Year, 2018 — WWS/MAF

_____________________________

W. Wade Stooksberry II: [In reference to Dr. Bill Cummings], I guess if he can’t counter a person’s arguments or criticism, he can always use his bully pulpit to personally attack them. I call that intellectual and moral cowardice.

Bill’s factual errors, logical inconsistencies, and intentional perversion of truth — evidenced here — do require a bit of space to adequately address. Anyone interested can peruse my piece, “”

What we have, at the heart of it, are weekly attacks on doctrinal Christianity, centered on the denial of Christ’s divinity, His atoning sacrifice by which we are redeemed from sin, and His bodily Resurrection which is our assurance of the truth. “Sauce for the goose…”; if Dr. Cummings is afforded a weekly platform to promote his vague musings, then I see no reason not to avail myself of the comments section in order to countermand them.

One of my favorite points to make is that if God exists, and has created a world characterized by death, disease, suffering, poverty, misery, oppression, violence, war, etc., but has not provided a means of redemption: Then “God” is, at BEST, either incompetent or indifferent. Or both. He is, indeed, akin to the Lovecraftian “Ancient Ones” — spiritual beings of immense power, who are neither good nor evil, merely indifferent — Who have no more regard for us, than we do for an ant.

Clearly, that leaves Bill’s dime store moralizing devoid of any moral impetus or category with which to validate it. The same can be said, of course, if God doesn’t exist at all. But Bill has remained rather evasive and ambiguous on that point. So far…

Franklin J. Hogue (photo, left): What makes you think that morality must be “validated” by a god? I suspect that your answer may be the familiar and oft-argued position that morality, good and evil, require a foundation somewhere “outside” time and chance, moored to something eternal and absolute, in a word, God. If so, you would have a difficult time defending that position, both as a matter of logic and in fact.

WWS: If “morality, good and evil” are not “moored to (and defined by) something eternal and absolute,” then they are by definition temporal and conditional (situational, relative). I’ll leave it to you to express your version of morality, good and evil (assuming you have one); why you adhere to it; and why I should likewise (assuming your version is in any way universal; if not — what are we talking about?). If you so choose. Please be sure your account conforms to reason, rationality, consistency, and coherency. If you can. Here’s mine:

“ ‘And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength.’ This is the first commandment. 31 And the second, like it, is this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.” — Mark 12:30,31

I believe these commands express the will and purpose and desire of the infinite, eternal Creator of our bounded space-time continuum, for the creatures He has endowed with free will — that is, us. Man. I am satisfied that the evidence for the truth of that proposition is abundant — no, more than that. Overwhelming. Convincing. Convicting, even…

FJH: What evidence can you provide in support of the claim that the two New Testament verses “express the will . . .” of God?

WWS: The evidence is the Resurrection of Christ. If He willingly endured death, in order to redeem us from the consequences (and, ultimately the very presence) of sin — the dreary litany referenced in my earlier message — and then rose from the dead after three days, transformed into a mode of existence that is, at a minimum, “hyper-dimensional” to our four (commonly called a “spiritual” mode of existence) — then that validates that He is who He claimed to be: the incarnation of God — “God in the flesh.” Which in turn validates the Scriptures, since “the volume of the Book” is written of Him. Now, what you have to determine is whether there is sufficient evidence for the Resurrection. And that is something that is a function of your free will. There is evidence — convincing, but not conclusive. As an attorney, you know that evidence can simply be ignored. Dismissed out of hand. If you’re looking for knockdown, empirical evidence of the Truth of Christ, you will remain unsatisfied. Because God has engineered our salvation to be a product of faith, in order that all may be saved. Anyone can accept a gift. Anyone can believe. Not everyone can produce the kind of good works that Bill assures us is the path to approval (of course, he never tells us the truth: that it is the path to HIS approval, not God’s.

If you choose to withhold your faith in Christ, you will of necessity believe — have faith in — SOMETHING. The question is, will that something be true? Well, obviously not, if Christianity is. But given that you don’t think that Christianity is true, then you are left with two rather dismal choices, that I mentioned earlier. Either God doesn’t exist, and our actions have no ultimate meaning or purpose in a mindless, indifferent universe of random processes:

Or whatever God DOES exist has engineered a world of woe, without any coherent means to achieve redemption. Not a God I choose to worship, when there is a clearly better alternative. “When men choose not to believe in (I would stipulate here, “the Biblical” — WWS) God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing: they then become capable of believing in anything.” — G. K. Chesterton

FJH: (H)istorical evidence for the “resurrection” of Jesus is too tenuous for me to accept as a historical event. There was a time when I did accept it — while earning my college degree in biblical studies (including Greek) and my seminary degree in theology. While writing my masters thesis on the theology of Wolfhart Pannenberg — who argues thoroughly for the historicity of the resurrection — I read extensively in the areas of hermeneutics and exegesis, as well as textual criticism (I also learned Hebrew in seminary), then went on to do a masters degree in philosophy, focusing on historical criticism and epistemology (theory of knowledge). Along the way, I concluded that the evidence in favor of the resurrection as a historical event was insufficient. After teaching philosophy for six years, I moved to Macon to attend Mercer Law School. I have spent my law career — in my 27th year — dealing in evidence sufficient to remove reasonable doubt from fair-minded people in courts of law.

I respect your conclusion that the resurrection occurred in history. But I disagree. Peace.

WWS: That’s fine, Frank. As I said, faith in the Resurrection — like belief in God itself — is entirely a function of free will. I believe our reality has been carefully constructed to ensure that characteristic. There is ample reason to believe either way — ultimately, we must choose for ourselves. I do hope you will reconsider your choice.

I find your credentials impressive. I am interested to know what, in lieu of the story of Redemption revealed in the Bible, you adhere to as guiding principles for life. I will assume you are not a theist, unless you state differently. If you are, can you account for a God who would allow so much suffering, without even providing a clear reason for it, or a means of rectification?

If you are a non-theist, can you explain on what basis one value system of good-bad, right-wrong, or system of morality, can be said to be superior to another? Do you agree with Bill’s vague assertion that we should “do good” to one another in a “community of love”? And if you do, can you tell me on what objective standard you base your agreement? Or on what basis, e.g., you could defend such an assertion against its opposite — i.e., that since we only have one life, and pleasure is the greatest good we can know, that we should spend our time selfishly pursuing our own personal pleasure? Or, put another way — what makes a person moral, according to your view? And why/how it does?

I have for at least 10 years been asking atheists/agnostics to provide me with a superior alternative to Biblical Christianity, in terms of a cohesive, consistent, rational and reasonable worldview. So far — no takers. Can you you provide one?

I ask in all earnestness, as I enjoy intelligent and civil conversation, especially with those who hold differing views than mine. I hope to hear from you — and either way, Happy New Year.

FJH: (T)hank you for (the) calm respectful response, a feature often missing here at macon.com. I will return to our discussion, but 2018 has started off way busier than I prefer, with court hearings, trial preparations, and such. Calm discussions on topics like this are enjoyable. In brief response, for now, however:

I am an atheist, which simply means that I do not believe that a conscious being has any causative role in the existence of the universe, nor any anthropomorphic attributes, such as “will” or “desire” with respect to us or the universe. We can talk more about that later.

As for “objective” standards for truth and morality, we would have much to discuss there. Nobody I know in my philosophical travels can defend the idea that standards are “objective,” if pressed sufficiently to clarify the notion (which usually means, as I think you mean, standards that are tethered to something outside space and time, something eternal and unchangeable).

But, and this may be more cryptic in this unsatisfying forum than you deserve, I reject “relativism.” The common and pejorative use of the term is well-deserved: It is a self-refuting bankrupt notion. I am not a moral relativist, nor a relativist about truth. Philosophically, I am an anti-foundational pragmatist. The best representatives of my views include John Dewey, Richard Rorty, William James, and most American pragmatists, but some European thinkers as well, most notably Jurgen Habermas.

As for my daily practice of morality, I try to be kind, mostly. I have always valued the list of traits Paul included in his beautiful paean on love: I Cor. 13:4-7: “Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. 5 It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. 6 Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. 7 It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.” Peace.

WWS: Frank. I can hardly have any squabble with you over being an atheist, seeing as I was once one myself. Our paths seem to be almost the reverse of each other’s. Like most in my — our? — generation, I was carted of to a denominational church as a lad. I’m grateful for that now, as it did instill in me an awareness of Jesus Christ (unlike the youngster who is reported to have recently asked, upon seeing a crucifix, “who is the man on the plus sign?”). But an hour or two a week of what seemed to me to be inexplicable wild tales was no match for the constant materialist indoctrination by the schools and media. And certainly no match for the allures of the fair sex, and the ubiquitous secular party lifestyle that defines modern life.

The thing is, I made the “mistake” of taking my atheism pretty seriously. And what I discovered is “that in the absence of God, all things are permissible.” And that can quickly lead to a very dark place. I cite as examples — “evidence”, if you will — some high profile mass killers (e.g., Vegas, Norway) who were expressing their godless, “nothing means anything” outlook by their actions. Add to that such mass killers as Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Pol Pot, and it quickly becomes evident what committed, philosophical atheism looks like, is capable of, when applied on a societal-economic-political-governmental level. Contrast that with a system built on the “inalienable rights of man, granted by our Creator” and the intrinsic value and worth of the individual, as made in God’s image — it just seems to me from a rational perspective, there is simply no comparison.

It gradually dawned on me that even if Christianity is untrue, it would be better for society to act as though it were true. Because it provided the best framework for achieving the happiest society, overall (I’m still waiting to hear of a better one). The story of my coming to the rational conclusion that the Bible really is propositional truth, and finally coming to accept Jesus as my personal Savior, is a long one — too much so to recount here. Suffice to say, it involved coming to an awareness of my own “lostness” and sinfulness (something we moderns or ancients for that matter, don’t like to come face to face with. But also the dramatic developments at the frontiers of science, especially astro- and quantum physics, and genetics (i.e., DNA) which increasingly validate the Biblical account of our reality. “IMO,” I suppose I should add.

As far as “morality” in general — I simply don’t trust man in that regard. I heard a great story just yesterday that illustrates the dynamic — at the risk of using too much bandwidth, I’ll relay it here. A little boy in MN rushed to the lake at the first hard freeze. But the ice was only 1/8 of an inch thick, and he fell through. He developed pneumonia. By the time he was well, he was afraid to walk on the ice again, even though assured it was safe, because the ice was 3-ft. thick by then.

The boy had great faith in a weak object — the thin ice. That is what we have when we have faith in our own morality, goodness, good works, etc. And he had weak faith in a sure object — the thick ice. Even if our faith in Christ is weak, He is able to hold us up. He is the proper object of our faith. Not ourselves.

If I may, I’d like to share a video with you that somewhat conveys the idea. My wife and I don’t make “Christian music,” per se — we’re Christians who make music, much of it written before, and while we were becoming, Christians; and which I now see define an arc that describes that path. This is one. “Keep saying the same old thing, my friend/ You’ll star in the romance of principled man/ at one with the process of salvation working out/ and finished by your own hand.”

The only thing between us, and knowing the truth of Christianity in eternity — or, perhaps, knowing nothing in oblivion — is that steady little drumbeat at our wrist. “Thump, thump, thump…

FJH: As the Jesuit motto says (attributed to Francis Xavier): “Give me a child until he’s seven and I’ll give you the man.” Your exposure to Christianity in your childhood and mine to atheism may account for our return to each in our adult years, after your sojourn in the wilderness and mine in Christianity in our teens and twenties. People don’t usually make such decisions based solely upon a sober analysis of facts and a keen use of logic. Instead, facts, logic, and argument are how we often justify the momentous decisions we’ve already made for reasons often mysterious to our own consciousness.

By the way, it’s false that “in the absence of God, all things are permissible.” Atheists can be highly ethical and good people, too, without the motivation of faith or the fear of damnation. Peace.

____________________________

Moderator’s comment:

This is an interesting debate that reminds me of one I had with a British neurosurgery colleague several years ago. One such point was whether morality requires the guidance of religion. It resulted in my writing a paper published in Surgical Neurology International entitled, “Religious morality (and secular humanism) in Western civilization as precursors to medical ethics: A historic perspective.”

In the case of the debate between Dr. Zrinzo and myself, we dealt with the issue of whether religious teachings, particularly from Judeo-Christianity, is necessary to sustain a moral code. Unfortunately the verbatim debate was lost when SNI developed a new website. Nevertheless, the main arguments survived in my paper.

Dr. Zrinzo claimed he won the debate because for him, the argument ended when we concluded that an atheist can be a moral person. But that was not the initial argument. Otherwise there would not have been a debate in the first place. I never disagreed with him on that point. On the other hand, I felt I won the debate because for the vast majority of humanity religion assists in upholding the moral code. Dr. Zrinzo used secular humanism for his arguments while defending atheism as moral relativism, if unwittingly doing so. I briefly referred to Aristotelian metaphysics and ethics, the scholastic arguments St. Thomas Aquinas and the basic realities of political science, history and common sense.

Interestingly, Mr. Hogue writes, “By the way, it’s false that ‘in the absence of God, all things are permissible.’ Atheists can be highly ethical and good people, too, without the motivation of faith or the fear of damnation.”

This is a similar variant to Dr. Zrinzo. The problem is that for most people the aphorism — ‘in the absence of God, all things are permissible’ — is still true, despite the fact that “atheists can be highly ethical and good people.” They are two related but independent facts that are not mutually exclusive propositions, as both Zrinzo and Hogue tried to argue.

There are many reasons why an atheist may be ethical, such as the fact a person may be inherently good, or because he may be made to be so because the fear of the law (as Aristotle has posited) or the fear the extra-legal consequences of acting badly, such as retaliation, as vendettas aptly testified.

I congratulate both Mr. Stooksberry and Mr. Hogue for their intellectual honesty, which is more than I can say for many debaters, particularly atheists claiming to be Christians to plainly deceive and use disingenuous arguments to subvert the faith of others — Biblical wolves in sheeps’ clothing. Mr. Hogue incidentally has been a noted criminal defense lawyer for over two decades, and wrote me:

“I don’t know if I qualify for the epithet ‘philosopher,’ especially since I got my Masters degree in the subject 30 years ago and have been a practicing criminal defense lawyer for the past 27 years. Real academic philosophers would probably not accept me in their ranks, since I’ve barely kept up with what’s going on in philosophy all these years. But, again, however you want to describe me; I’m just noting that “criminal defense lawyer” is more accurate than “philosopher.”

I went ahead and called him a philosopher. Mr. Hogue claims sincerely to be a pragmatist, but in my opinion he is much more an idealist, who otherwise knows himself as Socrates advised and who is obviously willing to face Pascal’s wager. Mr. Stooksberry has other articles posted here. He is a writer with wit and an excellent debater and musician — Miguel A. Faria, MD.

____________________________

The debate continues next Sunday with Part 2....

This article was originally published on January 28, 2018 on HaciendaPublishing.com.