- Articles

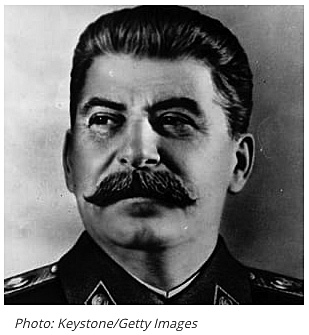

Stalin’s Mysterious Death

For weeks, Joseph Stalin had been plagued with dizzy spells and high blood pressure. His personal physician, Professor V. N. Vinogradov had advised that Stalin step down as head of the government for health reasons. That was not what Stalin wanted to hear from the good doctor. Soon the Professor would pay for this temerity and indiscretion with his arrest and alleged involvement in the infamous Doctor’s Plot (dyelo vrachey).

According to Dmitri Volkogonov in Stalin — Triumph and Tragedy (1991), the night before Stalin became ill, he inquired from Beria about the status of the case against the doctors and specifically about the interrogation of Professor Vinogradov. Minister of State Security Lavrenti Beria replied, “Apart from his other unfavorable qualities, the professor has a long tongue. He has told one of the doctors in his clinic that Comrade Stalin has already had several dangerous hypertonic episodes.”

Stalin responded, “Right, what do you propose to do now? Have the doctors confessed? Tell [Semyon D.] Ignatiev [Minister of the MGB security organ] that if he doesn’t get full confessions out of them, we’ll reduce his height by a head.” Beria reassured Stalin, “They’ll confess. With the help of Timashuk and other patriots, we’ll complete the investigation and come to you for permission to arrange a public trial.” Then, “Arrange it,” Stalin ordered. And from there, they went on to discuss other matters until about 4:00 a.m. on the morning of March 1, 1953.

Stalin was irritable and in a bad humor. He castigated his guests. Volkogonov based his account on the testimony of A.I. Rybin, who he personally interviewed. Rybin had been in the NKVD and later had become one of Stalin’s bodyguards. But Rybin, though, had not been there during Stalin’s final days. He had only been told what had happened by the guardsmen. And at the time Volkogonov had written his book those guardsmen could not be found or had refused to talk.(8)

Nevertheless, we do know that the guests had become a captive audience that evening and could not leave the Blizhnyaya, his nearer dacha in Kuntsevo, without Stalin’s permission. They simply had to wait until Stalin dismissed them. But Stalin was not finished. He was still complaining that the leadership, which included many of his guests that night, were basking on past glories — but “they were mistaken.” The implied threat to his inner circle was ominous. When Stalin finally got up and left, his shaken guests seized their opportunity and left the dacha. Georgy Malenkov and Lavrenti Beria, two of Stalin’s henchmen whom he allowed to commingle socially, left together in the same volga. The others left separately.

Stalin did not leave his chamber that morning and by noon his staff became worried. To make matters even more difficult, no one was authorized to enter his private chambers unless they were summoned. All through the afternoon the domestic staff and his personal guards worried and waited for Stalin to come out. They were finally reassured when an outside sentry reported that a light from his dining room had come on about 6:30 p.m. Volkogonov writes: “Everyone sighed with relief and waited for the bell to ring. Stalin had not eaten, or looked at the mail or papers. It was most irregular.” As late evening came, the domestic staff and guards began to worry anew. They debated what to do until sheer panic forced them to act. It was now 11:00 p.m., the evening of March 1, 1953.(8)

While Volkogonov interviewed Rybin years later, Russian journalist Edvard Radzinsky obtained documents that have even more bearing on Stalin’s final days from the secret Russian Archives. In his 1997 book, Stalin, Radzinsky relates that on March 5, 1977, the 24th anniversary of Stalin’s death, Rybin organized a little party that included the guardsmen who were “at the nearer dacha around the time when Stalin died.”(5)

The guardsmen remembrances were written down, and Rybin recorded the substance of the testimony in which all of them agreed:

“On the night of February 28-March 1, members of the Politburo watched a film at the Kremlin. After this they were driven to the nearer dacha. Those who joined Stalin there were Beria, Khrushchev, Malenkov, and Bulganin, all of whom remained there until 4:00 a.m. The duty officers on guard that day were M. Starostin and his assistant Tukov. Orlov, the commandant of the dacha, was off duty and his assistant, Peter Lozgachev, was deputized for him. Matryona Butusova, who looked after the Boss’s linen, was also in the dacha. After the guests had left, Stalin went to bed. He never left his rooms again.”(5)

Radzinsky found that Rybin had also recorded separate testimonies from the guardsmen. Starostin’s statement, which was the briefest, read: “At 19:00 the silence in Stalin’s suite began to alarm us. We (Starostin and Tukov) were both afraid to go in without being called.” Because they were afraid to go in, it was the newly deputized Lozgachev who went in, and “it was he who found Stalin lying on the floor near the table.” Moreover, according to Starostin, Stalin gave an order he had never given before and that statement was subsequently corroborated by Lozgachev. Stalin told his servants and guardsmen in the words of Tukov, “I’m going to bed. I shouldn’t be wanting you. You can go to bed too.”

But there was more to the story, and many years later after painstaking persistence, Radzinsky tracked down Peter Vasilievich Lozgachev, and the old guardsman, “still robust in spite of his age,” finally agreed to an interview about Stalin’s final days. According to Lozgachev “only light wine was drunk, no cognac, no particularly strong drink to make him ill.” Lozgachev’s account differs from Tukov’s in that according to Lozgachev, it was not Stalin who gave that unusual order but another guardsman, attachment Khrustalev, who had left the dacha at 10:00 a.m. on March 1. Only then was Khrustalev relieved by the aforementioned guards, Starostin, Tukov, and Lozgachev.

Before leaving them that morning, Khrustalev told them: “Well, guys, here is an order we’ve never been given before. The Boss said, ‘Go to bed, all of you, I don’t need anything. I am going to bed myself. I shouldn’t need you today.’ ” To Radzinsky, there was more here than meets the eye, and he clarifies the situation, “To be precise, [Lozgachev] heard it not from the Boss but from the attachment Khrustalev, who passed down the order, and left the dacha the next morning.”(5)

Radzinsky included the following narrative as recounted by Lozgachev:

“The next day was Sunday. At ten, as usual, we were gathered in the kitchen, just about to plan things for the day. At ten there was no movement that was the phrase we used when he was sleeping. And then it struck eleven — and still no movement. At twelve — still none. That was already strange: usually he got up between 11 and 12, but sometimes he was awake as early as 10. Soon it was one — still no movement. His telephones may have rung, but when he was asleep they were normally switched through to other rooms. ‘Starostin and I were sitting together and Starostin said: ‘There’s something wrong. What shall we do?’

“And indeed, what were we to do — go in to him? But he had always told us categorically: if there was ‘no movement’, we were not to go in. Or else we’d be severely punished. So there we were, sitting in our lodge (connected with his rooms by a 25-metre corridor), it was already six in the evening, and we had no clue what to do. Suddenly the guard outside rang us: ‘I can see the light in the small dining room.’ Well, we thought, thank God, everything was OK. We were all at our posts, on full alert, ready to go, and then, again… nothing. At eight — nothing. We did not know what to do. At nine — no movement. At ten — none. I said to Starostin: ‘Go on, you go, you are the chief guard, it’s your responsibility.’ He said: ‘I am afraid.’ I said: ‘Fine, you’re afraid, but I’m not about to play the hero.'(6)

“At that moment some mail was delivered — a package from the Central Committee. And it was usually our duty to hand over the mail. Mine, to be more exact. ‘All right, then,’ I said. ‘Wish me luck, boys’. We normally went in making some noise — sometimes even banged the door on purpose — to let him know we were coming. He did not like it if you came in quietly. You had to walk in with confidence, sure of yourself, but not stand too much at attention. Or else he would tell you off: ‘What’s all this good soldier Schweik stuff?’

“Well, I opened the door, walked loudly down the corridor. The room where we put documents was right next to the small dining room. I went into that room and looked through the open door into the small dining room and saw the Boss lying on the floor, his right hand out-stretched…like this [here Lozgachev stretched out his half-bent arm]. I froze. My arms and legs refused to obey me. He had not yet lost consciousness, but he couldn’t speak. He had good hearing, he’d obviously heard my footsteps and seemed to be trying to summon me to help him. I hurried to him and asked: ‘Comrade Stalin, what’s wrong?’ He’d wet himself and he wanted to pull something up with his left hand. I said to him: ‘Should I call a doctor?’ He made some incoherent noise — like ‘Dz…Dz…'(6)

“On the floor there was a pocket-watch and a copy of Pravda. And the watch showed, when I looked at it, half past six. So this had happened to him at half past six. On the table, I remember, there was a bottle of Narzan mineral water. He must have been going to get it when the light went on. While I was talking to him, which must have been for two or three minutes, suddenly he snored quietly… I heard this quiet snoring, as if he was sleeping.

“I picked up the receiver of the house phone. I was trembling and sweat beading on my forehead, and phoned Starostin: ‘Come to the house, quick.’ Starostin came in, and stood dumbstruck. The Boss had lost consciousness. I said: ‘Let’s lay him on the sofa, he’s not comfortable on the floor.’ Tukov and Motia Butusova came in behind Starostin. Together, we put him on the sofa. I said to Starostin: ‘Go and phone everybody, and I mean everybody.’ He went off to phone, but I did not leave the Master. He lay motionless, except for snoring. Starostin phoned Ignatiev at the KGB, but he panicked and told Starostin to try Beria and Malenkov. While he was phoning, we got an idea — to move him to the big sofa in the large dining room. There was more air there. Together, we lifted him and laid him down on the sofa, then covered him with a blanket — he was shivering from the cold. Butusova unrolled his sleeves.

“At that point Starostin got through to Malenkov. About half an hour had gone by when Malenkov phoned us back and said: ‘I can’t find Beria.’ Another half hour passed, Beria phoned: ‘Don’t tell anybody about Comrade Stalin’s illness’. At 3 o’clock in the morning, I heard a car approaching.”(5)

At this point, Radzinsky notes that it had now been four hours since the first phone call and many more hours since Stalin had been struck down by the sudden illness, and he had been lying there without medical assistance all that time. Malenkov and Beria finally arrived without Khrushchev.

Lozgachev continued his recollection:

“Malenkov’s shoes creaked. And I remember how he took them off and stuck them under his arm. He came in: ‘What’s up with the Boss?’ He was lying there, snoring gently… Beria swore at me, and said, ‘What are you panicking for? The Boss is sound asleep. Let’s go, Malenkov!’ I explained everything to him, how he’d been lying on the floor and how he could only make inarticulate noises. Beria said to me: ‘Don’t panic, and don’t bother us. And don’t disturb Comrade Stalin.’ And they left.

“And again, I was left alone. I thought I should call Starostin again and have him alert everybody again. I said: ‘If you don’t, he’ll die, and our heads will roll. Phone them and tell them to come.’ Sometime after seven in the morning Khrushchev turned up. [That was the first time that he made an appearance, noted Radzinsky]. Khrushchev, said ‘How’s the Boss?’ I said, ‘He’s very poor, there’s something wrong’, and I told him the whole story. Khrushchev said, ‘The doctors are on their way.’ Well, I thought, Thank God’! The doctors arrived between 8:30 and 9:00A.M.”(5)

Thirteen hours had now passed without Stalin receiving any medical assistance. Radzinsky hypothesized that Lavrenti Beria feared that Stalin intended to proceed not only with the conspiracy against the Jewish doctors, but also against some of the members of his inner circle, particularly Beria himself. He needed to act and so he did. Radzinsky posited that after Nikolai Vlasik, Stalin’s loyal, longtime bodyguard, had been arrested and implicated in the contrived Doctors’ Plot as well as the developing purge of the MGB, Beria, in an act of personal survival, recruited Khrustalev, a bodyguard strategically placed in Stalin’s current personal attachment. Reportedly, according to Molotov, Beria later claimed that the inner circle should thank him, with the words, “I did him in,” Beria boasted to Molotov, “I saved all of you!”(3)

Lozgachev continues:

“The doctors were all scared stiff…They stared at him and shook. They had to examine him, but their hands were too shaky. To make it worse, the dentist took out his dentures, and dropped them by accident. He was so frightened. Professor Lukomsky said, ‘We must get his shirt off and take his pressure.’ I tore his shirt off and they started taking his blood pressure. Then everybody examined him and asked us who was there when he collapsed. We thought, that was it, the end. They’ll just put us in the car and it’s goodbye. But no, thank God, the doctors came to the conclusion that he’d had a hemorrhage. Then there were lots of people, and, actually, from that moment we did not have anything to do with it. I stood in the door. People — the newly arrived — crowded around behind me. I remembered [MGB] Minister Ignatiev was too scared to come in. I said, ‘Come on in, there is no need to be shy.’ That day, the second of March, they brought Svetlana.”(5)

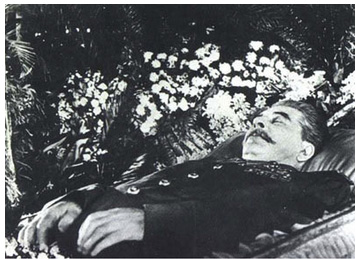

Between March 2 and March 5, when Stalin died, members of his inner circle were dividing the spoils of power. Beria had already gone through the Kremlin vault and removed incriminating documents. All the henchmen had returned to the dacha and assembled there to pay their respects, Beria, Malenkov, Khrushchev, as well as the disgraced quartet, Molotov, Mikoyan, Voroshilov, Kaganovich, and other members of the Presidium. They were regaining their confidence as the greatest mass murderer in history lay dying.

Radzinsky quoted the physician Professor Myasnikov: “Stalin sometimes groaned. At one point, only for a brief moment, his conscious gaze seemed to go round the faces by the bed. Then Voroshilov said: ‘Comrade Stalin, we, all your true friends and colleagues, are here. How are you feeling, dear friend?’ But his eyes were devoid of all expression already. We spent all day March 5 injecting things, and writing press releases. Politburo members walked up to the dying man. The lower ranks just looked through the door. I remember that Khrushchev was also by the door. In any case, the decorum in the hierarchy was well observed — Malenkov and Beria came first. Then Voroshilov, Kaganovich, Bulganin and Mikoyan. Molotov was not well, but came over two or three times, for a short time.”

Molotov himself recollected, “They told me to come out to the dacha… Stalin’s eyes were closed, and, when he opened them and tried to speak, Beria would come running and kiss his hand. After the funeral Beria laughed: ‘The light of science, ha-ha-ha!’”(5)

According to Svetlana, Stalin’s daughter, “Father’s death was slow and difficult…. His face became dark and different… his features were becoming unrecognizable…. The death agony was terrible. It choked him slowly as we watched… At the last moment he suddenly opened his eyes. It was a horrible look — either mad, or angry and full of fear of death…. Suddenly he raised his left hand and sort of either pointed up somewhere, or shook his finger at us all… The next moment his soul, after one last effort, broke away from his body.”

Svetlana also wrote, “Beria was the first to run out into the corridor, and in the silence of the hall, where everybody was standing around quietly, came his loud voice ringing with open triumph: ‘Khrustalev, the car!’”

To Radzinsky, this is another piece in the puzzle: “In this account by Svetlana, the memorable thing is the triumphant voice of Beria addressing Khrustalev! From all the assignees he was choosing Khrustalev!”(1)

Finally Radzinsky asked Lozgachev the whereabouts of the guard attachment:

“‘They got rid of everybody. They’d summon you and send you away from Moscow, ‘leave the city immediately and take the family with you’. Starostin, Orlov and Tukov decided to go and see Beria. To ask him not to send them away. So they went into his office, and he said: ‘If you don’t want to be out there, you will be down there.’ And he pointed down to the ground. So away they went.”

Radzinsky asked him, “And what became of Khrustalev?” Lozgachev responded, “Khrustalev fell ill and died soon after… Orlov and Starostin were given jobs in Vladimir, and I stayed at ‘the facility’ — the facility was empty, with me as superintendent. It was handed over to the Ministry of Health…. That was the end of the nearer dacha.'”(5)

Clinical Course of Stalin’s Illness

When the doctors arrived to treat Stalin on the morning of March 2, the Boss was soaked in urine and lay unconscious on the sofa. Both his right arm and leg were paralyzed with a right Babinski reflex (that is, right-sided hemiplegia consistent with a left cerebral stroke). He had a blood pressure of 190/110 with a pulse of 78. The doctors ordered absolute quiet, and eight leeches were applied behind his ears for slow bloodletting. Cold compresses and hypertonic enemas of magnesium sulfate were administered. Despite the doctors treatment, Cheyne-Stokes respiration appeared at 2:10 p.m. and Stalin’s blood pressure climbed to 210/120. Over the next two days, Stalin’s condition continued to deteriorate and he remained unresponsive.

On March 3, a flicker of hope appeared when the doctors observed that Stalin “reacted with open eyes to the speech of his comrades who surrounded him.” But this was only momentary. Stalin soon lost consciousness and never regained it.

On March 4, Stalin began to hiccup uncontrollably and vomit blood. On March 5, the sweating became profuse and the pulse undetectable. Stalin did not respond to oxygen or injections of camphor and adrenaline. Stalin’s death was recorded at 9:50 p.m. on March 5, 1953.(7)

Final Diagnosis: “Arising on March 5 in connection with the basic illness — hypertension and the disruption of circulation in the brain — a stomach hemorrhage facilitated the recurrent collapse, which ended in death.”

But in the final draft of the report submitted to the Central Committee, Brent and Naumov note: “All mention of the stomach hemorrhage was deleted or vastly subordinated to other information throughout in the final report.”(3)

It was reported that Stalin only drank diluted Georgian wine the night before his illness of March 1. Brent and Naumov suspect in one scenario that Beria with the complicity of Khrushchev (whose memoirs, Khrushchev Remembers, relating to the events of Stalin’s final days have been found to be unreliable),(5,6,8) slipped warfarin, a transparent crystalline substance into the wine. Warfarin is a tasteless chemical that in 1950 had just become patented and available in Russia as a blood thinner for patients with cardiovascular disease, and later, widely used as rat poison. A hypertensive hemorrhage of itself would have caused a stroke as Stalin sustained, but it would not necessarily be associated with gastrointestinal or renal hemorrhaging. Warfarin, on the other hand, could have produced both a hemorrhagic stroke as well as a bleeding disorder affecting multiple organs. The autopsy findings would be critical and, fortunately, just recently they have become available.

AUTOPSY OF THE BODY OF J. V. STALIN: “Post-mortem examination disclosed a large hemorrhage in the sphere of the subcortical nodes of the left hemisphere of the brain. This hemorrhage destroyed important areas of the brain and caused irreversible disorders of respiration and blood circulation. Besides the brain hemorrhage there were established substantial enlargement of the left ventricle of the heart, numerous hemorrhages in the cardiac muscle and in the lining of the stomach and intestine, and arteriosclerotic changes in the blood vessels, expressed especially strongly in the arteries of the brain. These processes were the result of high blood pressure.

“The findings of the autopsy entirely confirm the diagnosis made by the professors and doctors who treated J. V. Stalin.

“The data of the post-mortem examination established the irreversible nature of J. V. Stalin’s illness from the moment of the cerebral hemorrhage. Accordingly, the energetic treatment which was undertaken could not have led to a favorable result or averted the fatal end.

“U.S.S.R. Minister of Public Health A. F. Tretyakov; Head of the Kremlin Medical Office I. I. Kuperin; Academician N. N. Anichkov, President of the Academy of Medicine; Prof. M. A. Skvortsov, Member of the Academy of Medicine; Prof. S. R.” (2)

Obviously, the above signatories in the Ministry of Health included in the report as much as was possible to put in writing from a political standpoint, without getting their own heads into the repressive Soviet noose! They also correctly protected the physicians who treated Stalin. Needless to say the Doctors’ Plot episode was very fresh in their minds.(4)

While prudently citing hypertension as the culprit, the good doctors left behind enough traces of pathological evidence in their brief report to let posterity know they fulfilled their professional duties, as best they could, without compromising their careers or their lives with the new masters at the Kremlin.

High blood pressure, per se, commonly results in hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage and stroke but does not usually produce concomitant hematemesis (vomiting blood), as we see here in the clinical case of Stalin, and a further bleeding diathesis affecting the heart muscle, scantily as it is supported by the positive autopsy findings.

As I have written elsewhere, we now possess clinical and forensic evidence supporting the long-held suspicion that Stalin was indeed poisoned by members of his own inner circle, most likely Lavrenti Beria, and perhaps even Khrushchev, all of whom feared for their lives.(4) But Stalin, the brutal Soviet dictator, was (and still is in some quarters of Democratic Russia) worshipped as a demigod — and his assassination would have been unacceptable to the Russian populace. So it was kept a secret until now.

References

1. Alliluyeva S, Chavchavadze P. Only One Year. Translated by Paul Chavchavadze. NY, Harper & Row, 1969.

2. Autopsy of the Body of J.V. STALIN. Complete text. Pravda. 1953. p. 2.

3. Brent J, Naumov VP. Stalin’s Last Crime: The Plot Against the Jewish Doctors, 1948-1953. NY: Harper Collins; 2003. p. 312-22.

4. Faria MA. The Jewish Doctors’ Plot—The aborted holocaust in Stalin’s Russia! A book review of Stalin’s Last Crime: The Plot Against the Jewish Doctors, 1948-1953 by Jonathan Brent and Vladimir P. Naumov. 2011. Available from: https://www.haciendapublishing.com/articles/jewish-doctors%E2%80%99-plot-… .

5. Radzinsky E. Stalin, 5th ed. Translated by HT Willets. NY: Anchor Books; 1997. p. 566-82.

6. Radzinsky E. The Last Mystery of Stalin. Sputnik, Moscow: 1997.

7. The History of the Illness of J. V. Stalin. Secret Report submitted to the Central Committee, July 1953. Quoted and referenced in Brent and Naumov, ibid.

8. Volkogonov D. Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy. Edited and translated by Harold Shukman. NY: Grove Weidenfeld; 1991. p. 567-76.

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is a former Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine; Former member Editorial Board of Surgical Neurology (2004-2010); Recipient of the Americanism Medal from the Nathaniel Macon Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) 1998; Ex member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002-05; Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002); Editor Emeritus, the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons (AAPS); Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and .

This article was originally published in Surgical Neurology International and also featured in RealClearHistory.com on June 26, 2012.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Stalin’s Mysterious Death. Surg Neurol Int 2011;2:161. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/stalins-mysterious-death/

Funeral of Joseph Stalin video:

Copyright © 2011, 2015, Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.