- Articles

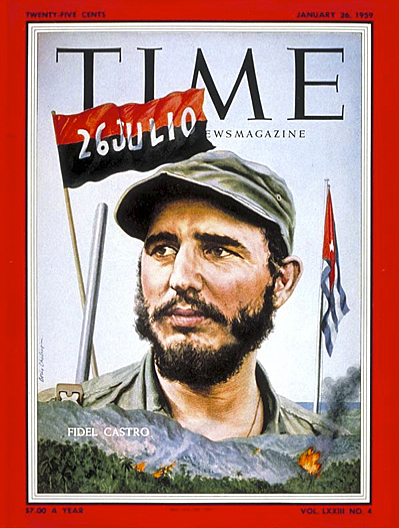

Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement

The 26th of July is the most sacred day of Cuba’s communist revolution, commemorating 51 years since that fateful day that began the insurrection against Fulgencio Batista. The article that follows is excerpted from Chapter Four of Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.’s book, Cuba in Revolution — Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). The references refer to citations in the text of his book.

The date of the Moncada Barracks attack, July 26, 1953, would give Fidel Castro the name of his organization, the 26th of July movement, and would become the most sacred date of communist Cuba. And, speaking of sacredness, why did Fidel Castro choose the 26th of July for the commencement of his Revolution? Sources tell us Fidel chose July 26 because the patron saint of the city of Santiago de Cuba was the Apostle James the Elder. In medieval Spanish tradition he was resurrected as Santiago the Moorslayer, the avenging angel of the Spanish knights during the Reconquista, as well as the charging fury that led the indomitable conquistadores of Hernán Cortes when battling the Aztecs of Mexico.

The saint was honored every July 25, which also coincided with the end of the sugar harvest, hence the day of the most joyous celebration in Santiago de Cuba. Fidel Castro, “the new Moorslayer, would destroy Batista.” Indeed, Fidel had told his Ortodoxo friend, José Pardo Llada, after Batista’s bloodless March 10, 1952 coup d’état in which Batista had seized the government, “We have got to kill that Negro.”

It is of interest that Fidel has admitted in moments of candor that the Moncada attack was carried out for sensationalism to stir up the public and to begin his Revolution with a splash. The fact is that despite the infamous Batista coup of March 10, 1952, Cuba was and remained prosperous and at peace. There was no popular protests or public outcry, except for the measured protests by the intellectuals chiefly in Havana. Fidel, then, had to do something spectacular to get the people’s attention and rally them against Batista. In Fidel’s view, the Moncada Barracks attack was “a gesture which would set an example for the people of Cuba.”

On July 26, 1953, Fidel Castro, along with his brother Raúl, led an attack on a remote outpost, the Moncada Barracks, in Oriente province, the easternmost province of Cuba. As discussed above, the fortuitous day was chosen after a major celebration in Santiago de Cuba. He expected Batista’s soldiers to be drunk and stuporous when his band of revolutionaries would surprise them at the crack of dawn. He had 160 men, which included as mentioned, his brother Raúl, Abel and Haydée Santamaría, and several others like Juan Almeida, who would become better known as the Revolution unfolded. Fidel Castro and the principal group of assailants were to attack the main post in the barracks.

In the meantime, the doctor in the group with Abel Santamaría and the two women, Haydée Santamaría and Melba Hernández, were to secure the infirmary. But everything went wrong. In the lead vehicle, Ramiro Valdés encountered one of the guards and smashed his face in with the butt of his rifle. The vanguard of the group surprised the sentries, who, nevertheless, were able to warn the garrison. They suffered eight deaths in the ensuing gunfight. Fidel Castro did not even enter the compound. In the infirmary, the small group viciously killed the sleeping soldiers, accounting for the majority of the 22 enemy casualties.

Abel and the women were captured by Batista forces, and the soldiers, upon discovering the slaughter of their sick and wounded comrades in the infirmary, retaliated. Abel was tortured and brutally killed while in police custody. He would later become an icon of the Revolution. In the chaos that followed, 56 revolutionaries were killed, the majority of them after their capture, in retaliation for the infirmary massacre.

Years later, Abels sister Haydée, a member of the ruling nomenklatura, would commit suicide while working in Castro’s communist government as director of the States official publishing house, Casa de las Américas. She had become disillusioned, it seemed, with the course of the Revolution and her equally failed marriage with playboy and compañero Armando Hart, Minister of Culture.

Comandantes Juan Almeida and Ramiro Valdés would remain in Fidel’s revolutionary hierarchy for decades(Almeida as Communist Party apparatchik and Valdés working in the dreaded internal State security apparatus). Valdés, along with the dissolute quartet of Osmony Cienfuegos, Sergio del Valle, José Abrantes, and Manuel Piñeiro (“Red Beard”), would put Batista police and military chiefs such as the Salas Cañizares, the Masferrers, the Mirabales, and Estéban Ventura to shame in using effective repressive tactics to squelch opposition and spread terror.

And yet, Batista forces in that remote outpost fought back and defeated Fidel and his ragtag band. Fidel, who stayed safely behind during the attack, was also protected after his arrest and apprehension by the Archbishop of Santiago de Cuba, Mons. Enrique Pérez Serantes. Fidel and the members of his band were rounded up, tried, and convicted. Fidel’s failed legal defense of himself at his trial on October 16, 1953 became a major revolutionary document, History will absolve me. While in prison, Fidel accused his wife Mirta Diaz Balart, who he abandoned along with their infant son, of collaborating with the dictator’s Internal Ministry. Mirta would be forced to divorce Fidel.

Interestingly, before the Moncada Barracks attack, Fidel had visited Batista at his palatial home at least twice. On one occasion, accompanied by his brother-in-law, Rafael Diaz Balart, Fidel had promised the dictator that he would support his government. Before that, when Fidel and Mirta went on their honeymoon in 1949 to the Bronx, New York, they had both received a $500 bill from Senator Batista as a wedding present.

For his part, Batista, the corrupt and vengeful dictator, released Fidel Castro and his men from prison in 1955 as a gesture of national reconciliation in a general amnesty release. Fidel and his men had been treated exceptionally well. While Fidel and his conspirators were sentenced by the presiding judge specifically to be incarcerated in the dreaded old fortress prison of La Cabaña to serve his sentence of fifteen years, the Cuban Minister of the Interior, Ramón Hermida, ordered them, instead, sent to the newest Modelo Prison on Isla de Pinos. There, they were classified as political prisoners, and rather than being treated harshly and inhumanely, they were treated with the same respect and special privileges that Batista gave to “political prisoners” at the time. As we shall see, when the tables are turned and Fidel is doing the incarcerating, things would be totally different.

Yes, the Moncada assailants who survived the attack and the immediate vengeful aftermath were treated favorably with special privileges following their prosecution and conviction. While in prison, Fidel and his conspirators were given books and magazines and were allowed to keep subversive political literature, including books of Marx, Lenin, and other revolutionary subversives.

Quirk notes that while at the modern Modelo Prison, Fidel was more influenced by Nikolai Ostrovski’s How the Steel Was Tempered and Hewlett Johnson’s (the “Red Dean” of Canterbury), The Secret of Soviet Strength, than by the more lengthy and soporific works of Marx and Lenin. Thus, Fidel had ample time to expand his egalitarian, collectivist sentiments and transform them into solid, communist ideology. Quirk sees Fidel and his writings and speeches as being those of an idealist egalitarian who admired FDR’s New Deal and who only later, after the Revolution, pragmatically or for personal reasons, became a socialist. “Because,” writes Quirk, “he was open to the moral, if not intellectual appeal of Marxism.”

Any careful study of Fidel Castro’s pronouncements during his years in prison in 1953-1954 and his actions thereafter, 1955-1958, reveal that the young autocratic revolutionary was carefully adding details to his elitist mentality and collectivist frame of mind. He was becoming an authoritarian, whether fascist or communist, only time would tell, but by the 1950s, fascism was certainly on the decline, whereas communism was on the rise.

In addition to the works of communist authors, Fidel Castro treasured Benito Mussolini’s volumes and avidly read the works of Spanish Falangist José Antonio Primo de Rivera, both of whom are said to be on the far right side of the political spectrum. Let me explain.

Since the turbulent days of the early 1790s, when the Jacobins and Girondins held the raging debates at the National Convention during the French Revolution, the meaning of “right” and “left” which was dictated by the seating arrangement of the delegates, has changed considerably. Then, it was moderate versus radical in the ideological political spectrum. Today, it supposedly separates liberal from conservative.

As Fidel’s choice of political books demonstrates, collectivist writings appeal to authoritarians because birds of a feather tend to flock together. All forms of authoritarianism and collectivism — whether national socialism (Nazism), communism, or their seemingly milder cousins, corporativism and fascism — are, in reality, all nuances of the same ideology of the left side of the political spectrum, where the collective power of the State becomes all powerful and supreme over the individual.

On the other end of the spectrum, we find anarchy, the extreme condition of having no government at all, which occupies the far, extreme right. Imagine then, a horseshoe with an accentuated bend, the ends almost meeting at the extreme right and left. The gap, a narrow one, can be easily traversed from one side to the other by the extremisms of a police State on the one hand or rampant terrorism and chaos on the other. The end result is anarcho-tyranny. Anarchy, tyranny, or their confluence are neither conducive to economic prosperity nor political freedom.

In the stable middle of the horseshoe where the bend occurs, lay the blessings of constitutional rule, as is the case in the United States and was the case, to some extent, in Cuba with the constitutions of 1901 and 1940. Restoration of the Constitution of 1940 is what Fidel promised the Cuban people, but never delivered, and never intended to deliver.

Whether Fidel’s Marxism was inchoate or inveterate in 1955 or 1958, or even 1959 or 1961, in the final analysis, becomes moot. In the end it does not matter for how long he deceived the Cuban people. The reality is that he betrayed the Cuban people and did not reveal his Marxism-Leninism until he was fully entrenched in power with his State Security apparatus equally and firmly in place. No matter how much the United States had tried to appease him, tolerated his insults, or even forgiven the nationalization of U.S. properties (i.e., expropriations without compensation), in the end, Fidel would have turned to the Soviets. Deep inside, he had become, like Raúl and Ché, a dedicated communist.

Communism allows autocrats to maintain power over the individual citizens. It is a symbiotic relationship. Fidel Castro needed communist tactics to seize power, and the communists needed a populist autocrat to accomplish their objective. They worked hand in glove and wanted similar ends totalitarianism and collectivism while crushing individual freedoms and holding onto power.

To camouflage his true intentions, Fidel allied himself to Cuban politicians and personalities as long as they were useful to him to make himself more acceptable, to emanate, to effuse the aura of respectability he had always yearned for and desired. For example, after the Revolution, there was Manuel Urrutia, who had been a judge voting favorably at the trial of Granma survivors captured by Batista’s soldiers, and Prime Minister José Miro Cardona, a former law professor at the University of Havana. After Fidel took power, he would force Miro Cardona out of office as Prime Minister, and the good judge, Urrutia, out of the presidency. Fidel would eventually assume the duties and capacities of both of these offices. Before that, he allied with and took money from former foes, like Justo Carrillo and even mortal enemies like Prío Socarrás, in his quest for power. And he never kept any accounting of the monies received.

The truth is the Cuban people did not know Fidel, and what they (and the world) learned came mostly from the image Herbert Matthews created after he visited the Sierra Maestra, and the articles he wrote for The New York Times and faithfully reprinted in Bohemia, Cuba’s popular and largest circulation weekly magazine, as well as the photographs of Matthews and Castro jovially conversing in the Sierra Maestra. To the very end, until it was too late, Cuba’s and America’s major magazines and newspapers kept the Cuban people benighted about Fidel’s intentions, his past shenanigans, and his authoritarian proclivities. The fact is Fidel was always an autocrat, and he became more so as the years passed, although he was careful to conceal it from the Cuban people.

After their imprisonment, Fidel and his comrades were kept in the hospital wing of the Modelo Prison away from common criminals. There, Fidel was permitted to organize and conduct a school for his fellow insurgents where political economy, philosophy, and history were taught. Not until the audacious prisoners insulted President Batista on an official State visit to the Isla de Pinos prison did the situation change, and their privileges were withdrawn. By then, Fidel and his prison conspirators would have less than eight months left to spend in prison. Moreover, while incarcerated, Fidel continued to have friends in the press and on the radio air waves who helped to keep his name alive with the populace – friends like Luis Conte Agüero and José Pardo Llado, and in Bohemia, writers like Jorge Mañach and Ernesto Montaner, as well as the magazines influential chief editor, Miguel Angel Quevedo.

And, of course, there was ex-communist Carlos Franqui, who helped Fidel Castro as a journalist and radio broadcaster beginning in 1955 and who would later head clandestine Radio Rebelde from the Sierra Maestra. After the triumph of the Revolution, Franqui would also edit the official organ Revolución. All of these capable journalists would later see the light and be forced into exile.

In 1955, when Ramón Hermida, Batistas Minister of the Interior, found that Fidel was despondent in prison because of the break up of his marriage with Mirta Balart, he went to see young Castro to cheer him up. Fidel had found that Mirta had a sinecure job with his Ministry, and this was not only an embarrassment to Castro but also an actual “betrayal.” Hermida reassured him saying, “Don’t be impatient. You’re still a young man. Keep calm. Everything will pass.” Could you imagine the sanguinary and dissolute Ramiro Valdés or José Abrantes or any of Fidel’s henchmen in the Ministry of the Interior, visiting a prison cell to give hope and encouragement to a gusano (worm), serving time in Castro’s jails after leading a counterrevolutionary insurrection?

What a difference from the way Castro’s jails treat thousands of political prisoners today! Allow me to digress and mention here the barbaric and ghastly treatment of Cuban physician, Oscar Elias Biscet, a prisoner of conscience who only protested human rights abuses in Cuba. He pleaded for Castro’s communist regime to honor the U.N. Charter of Human Rights. He was thrown in jail after a sham trial. Requiring medical attention, he has been denied medical care, tortured, and kept in solitary confinement.

Dr. Biscet completed his sentence in 2002 (incarcerated from November 3, 1999 October 31, 2002) only to be rearrested and incarcerated on December 6, 2002, in another of Castro’s waves of repression. In April 2003, Dr. Biscet was one of 75 dissidents given long prison sentences (25 years) for engaging in what the communist dictator called “an attempt to undermine the social order.” His brutal treatment and suffering continues, but he remains unbroken.

This article is extracted from Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002) by Dr. Miguel Faria.

Dr. Faria is a former professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History at Mercer University School of Medicine. He is the author of Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His books are available at .

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement. HaciendaPublishing.com. July 27, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/fidel-castro-and-the-26th-of-july-movement/

This article was also published on NewsMax.com on July 26, 2004.

1 thought on “Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement”

The following video was recommended by Dr. Miguel Faria because it has an interesting CIA-William Morgan connection. An American son tries to locate his lost father in Cuba during the early Castro revolution. https://vimeo.com/20962739