- Articles

Caesar — The Conquest of Gaul, Civil War, and Death of Pompey the Great

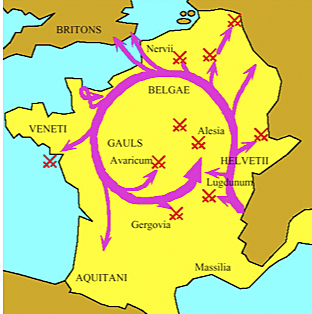

Caesar: Let the Dice Fly (1997) is the fifth installment of the “Masters of Rome” historical novel series by author Colleen McCullough. This tome encompasses the period from 54 B.C., when Julius Caesar invaded Gaul and Britannia, and ends with the heinous and treacherous assassination of Pompey the Great in Egypt in 48 B.C. The book opens with Caesar leading his legions in the second expedition into Britain, “the land at the western end of the world,” accompanied by allied kings, Mandubracius, King of the Britannic Trinobantes, and King Commius, leader of the Atrebates of Gallia Comata (“Long-haired Gaul”). The campaign is directed north of the Tamesa (Thames) river against the undefeated Cassi tribe led by King Cassivellaunus. The Cassi fought valiantly using archaic chariots, reminding the Romans of the Homeric epics.

Although far away in the northwest, Caesar has kept himself informed of events in Rome by his paid agents as well as letters from his son-in-law, Pompey Magnus, who now married for six years to Caesar’s lovely daughter, Julia, has contentedly improved his grammar and his manners. But then suddenly Julia dies following childbirth and his political link to Caesar is severed. Moreover, Marcus Licinius Crassus, the third member of the First Triumvirate, died at the hands of the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C., ending whatever reconciliation was possible between the two great Romans, Caesar and Pompey.

We learn in this tome, the exceptional tale of Cato divorcing his charming wife, Marcia, from a marriage to which both have been devoted and remained deeply in love. Cato, stoic as always, agreed to a divorce to please his friend, the aging orator and advocate, Hortensius, who then married Marcia. I will say more about this curious affair later.

The adoration of Julius Caesar “the autocrat” continues in this volume and nothing detracting from his grandeur is permitted in McCullough’s hagiography of Caesar.(1-2) For example Caesar’s poignant and telling story of when he served in Spain as quaestor (69-68 B.C.) that upon coming to a statue of Alexander the Great, Caesar cried because at age 32 the great Macedonian had conquered the world, while he, Caesar, was a mere quaestor — is not told in this one or her previous books, because it would have diminished her hero and detracted from his imperturbable self-confidence. Ironically, the same statement could have been said in reference to Caesar’s rival, Pompey, who by age 24 was an accomplished general, and was soon, like Alexander, to conquer foreign enemies on three continents. Caesar’s epilepsy is also not mention as it would have diminished the perfection of the demigod.

Once again, McCullough’s dislike of the boni, the Optimate political faction, particularly Cato (photo, left), is intense. And now that his nephew Brutus has come of age and become one of Cato’s disciples, he too, is crucified with a vengeance on these pages. In the voice of Caesar: “That poor, pathetic, spineless boy of her [Servilia] is now a poor, pathetic, spineless man. Face ruined by festering sores, spirit ruined by one enormous festering sore, Servilia.” Brutus is not only portrayed as being disfigured physically but also morally, an avaricious coward: “And he likes money too much… He didn’t want to go to a province wracked by war. To do so might expose him to battle.”(3)

Pompey, Cato, Brutus, and the boni frequently awake the mythological Fury in McCullough. Pompey is a two-faced ostentatious fool who cares not one iota for his dignitas, but only for the aristocratic lineage of his wives. Never mind he had conquered more than any other Roman general and doubled the size and tribute of Rome, pacified the Mediterranean, and subdued Asia Minor and much of the Near East. Cato is a rancorous drunkard, a block head, who only wants to frustrate the “dreams” of the “quintessential Roman,” Julius Caesar. Cato wants Brutus to marry Porcia because of his fabulous wealth. Nevermind Cato the Stoic was the most honest, sober-minded, and most incorruptible man in Rome. In short, McCullough makes the characters fit her own preconceptions and political prejudices, to be what she wants them to be, not what historical context or common sense would have predisposed them to be. And thus she violates her dictum of preserving objectivity and historical veracity, as she insisted in one of her glossaries, “In this Roman series I have severely limited my novelist’s imagination, and do not allow it to contradict history.”(4)

In this tome, McCullough, anticipating the role Brutus will play in history, becomes the incarnated Fury, lashing out time and again at Brutus. Brutus is described as a disfigured timid man who loves money as a means to the acquisition of power and has now turned to Cato his uncle (and idol) and to the boni because Caesar broke the betrothal between Brutus and Caesar’s daughter Julia, “the love of his life.”(5) And his own adulteress seductress mother, the wicked Servilia, speaks of her own son, Brutus, as “Anaemic, flaccid, impotent…,” castigating but also revealing that some of the peccadilloes and vulgar innuendos contained in a previous volume, Caesar’s Women, spilt over into this volume too. And I do mean vulgar because the sexual encounters and the language utilized in McCullough’s sexual scenes, particularly involving Servilia, are not sensual or erotic, but cut and dry vulgar.

Suffice to say, Brutus, as an ultimate mortal enemy of Caesar, is not the historic Brutus, the Republican patriot and assassin who followed the path of his revered ancestors — Lucius Junius Brutus, the founder of the Republic, and Gaius Servilius Ahala (via his mother Servilia), who slew Maelius for attempting to restore the monarchy during the early Republic. And bookish Brutus had “pretensions to intellectualism was no deeper than the skin on sheep’s milk.”(6) In short, the republican boni, particularly Brutus and Cato, are thinly veiled monsters, who only want to frustrate Julius Caesar because they suspect (imagine, without cause) that the “quintessential Roman,” if unchecked, would end up overthrowing the Republic! A very prescient thought of the impending calamity, indeed!

Porcia, who has always been in love with her cousin Brutus and harbors republican sentiments, is not spared in the castigation. She is described as “dismally plain and not very feminine…flat chest, wide shoulders, narrow hips…and when she met her dear cousin Brutus, she emitted the same neigh of laughter Cato did, and showed the same big, slightly protruding top teeth; her voice too was like his, harsh, loud, and unmelodic.”(6) The conversations of the boni are always rancorous and vindictive, whereas those between Caesar and his friends are always constructive and thoughtful — that is, when they are not admiring or cajoling Caesar.

The necessary contradictions in McCullough’s Caesar are daunting. About the war in Gaul, Caesar says, “This year must see this futile, pointless, wasteful war finished for good.”(7) This of course is a reasonable statement, except that Caesar was conquering Gaul of his own initiative without direction or orders from the Senate, which only approved his conquests as a fait accompli. The subjugation of Gaul was, plain and simple, accomplished with much bloodshed and suffering to enhance his own dignitas and ultimately gain political power in Rome. Unlike Hannibal, Alexander, Pompey the Great, the Scipios, or even Napoleon, to whom military adventures were carried out for military conquests or for personal and national glory — Caesar’s military genius was cultivated solely for political gain and the attainment of supreme power in Rome. When Sulla marched on Rome, he had a legitimate grievance against the State. Caesar did not, and by crossing the Rubicon and marching on Rome, Julius Caesar placed his own welfare and dignitas ahead of the welfare of Rome.

The battle of Alesia is well told, the circumvallations and battlements are well explicated and the surrendering of Vercingetorix is poignantly depicted. Caesar in Gaul is indeed an outstanding general, except in McCullough’s novel he does not take risks! The general always knows what is best to do, plans well, and never makes a mistake, none of which was always historically true. His enemies were awed and lost battles to Caesar before they are ever fought. Caesar is even idolized by one of his main antagonists, the Chief Druid Priest, Cathbad, who is spiritual leader of the tribes of Gaul, the same tribes Caesar is actively exterminating for his own political gain. Cathbad is awestruck by the conqueror: “It is interesting that a man so welded to the political attitudes of his country can also be so truly religious.” Imagine this, not only is Caesar religious, but the genocidal general was sent by the Tuatha, the pantheon of the gods of Gaul, who loved Caesar! Imagine Cathbad, Caesar’s main antagonist in Gaul, swoons over the future dictator of Rome, ” Oh he did look every inch the conqueror!”(8)

And here is the Populare politician, Gaius Scribonius Curio (d. 49 B.C.), a Caesar adherent, exalting Caesar to his wife Fulvia, the granddaughter of Gaius Gracchus: “He is a complete autocrat… but ye gods, Fulvia, he was born a dictator… sprung fully armed from the brow of Zeus!”(9)

The fact is that Caesar used the southern migration of the Helvetii, which he intercepted, as an excuse to march his legions into Transalpine Gaul in 58 B.C. and painstakingly conquering it; but he took unnecessary risks and committed many blunders, which were converted into victories only because of the courage and discipline of his superbly trained legions. Caesar was seriously ambushed by the Belgae tribes, and the raids in Britain were almost disasters, saved once again by the discipline and training of his soldiers. As a great writer, Caesar’s dispatches, written in the third person, described the war and his successes but not his blunders, becoming excellent propaganda.

The conquest of Gaul then proceeds with novelistic license, but it is nevertheless enthralling reading. How can it not be? And yet, novelistic brilliance sparkles, not in the slavish praise and contrived goodwill of Caesar, but it unexpectedly shimmers in several but brief occasions in the person of Cato, despite McCullough it seems. One instance is the poignant story of Cato’s divorce and re-marriage to his beloved Marcia, and the whole Marcia-Cato-Hortensius-Philipus affair. The nobility and integrity of Cato breaks through in the episode of Cato’s annexation of Cyprus. And most surprisingly Cato’s humanity is brought forth in his visit and stoic advise to Hortensius, as the old man lay dying, and in his friendship, correspondence, and final moments also with his friend and son-in-law, the boni leader, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus (102-48 B.C.).(10)

How ironic that after continually slandering the hated boni and the Pompeians, it is not the blood and guts of Caesar’s battles, nor his sexual intrigues in Servilia’s bed, or the rough and tumble politics in the Roman Forum — but the personal stories and tragedies of the Optimate Republicans, including the death of Pompey, that at times make this tome shine in eloquent prose and humanity!

Read Dr. Faria’s review of the previous installment or the next installment of McCullough’s “Masters of Rome” series.

References

1) Faria MA. Fortune’s Favorites in Ancient Rome — Sulla, Pompey, Crassus and Caesar. A book review of Fortune’s Favorites (1993) by Colleen McCullough. HaciendaPublishing.com, July 8, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/fortunes-favorites-in-ancient-rome–sulla-pompey-crassus-and-caesar.

2) Faria MA. Caesar’s Women — McCullough’s Idolatry and Politics in Ancient Rome. A book review of Caesar’s Women (1997) by Colleen McCullough. Haciendapublishing.com, August 14, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesars-women-mcculloughs-idolatry-and-politics-in-ancient-rome.

3) McCullough C. Caesar: Let the Dice Fly. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1997, p. 42.

4) McCullough C. Fortune’s Favorites. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 1993, p. 865.

5) McCullough C. Caesar: Let the Dice Fly. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1997, p. 160-163.

6) Ibid., p. 164-165.

7) Ibid., p. 328.

8) Ibid., p. 310-311

9) Ibid., p. 488

10) Ibid., p. 363-391

Written by Dr. Miguel Faria

Dr. Miguel A. Faria is the author of Cuba in Revolution: Escape from a Lost Paradise (2002) and of numerous articles on politics and history, including “Stalin’s Mysterious Death” (2011), The Political Spectrum — From the Extreme Right and Anarchism to the Extreme Left and Communism (2011); Violence, mental illness, and the brain — A brief history of psychosurgery (2013), etc., all posted at his website HaciendaPublishing.com.

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Caesar — The Conquest of Gaul, Civil War, and Death of Pompey the Great. HaciendaPublishing.com, October 6, 2013. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/caesar–the-conquest-of-gaul-civil-war-and-death-of-pompey-the-great.

(Caesar: Let the Dice Fly by Colleen McCullough (1997). William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, NY, 664 pages.)

The photographs used to illustrate this exclusive article for Hacienda Publishing came from a variety of sources and do not necessarily appear in Colleen McCullough’s Caesar. An unillustrated version of this article appeared also in Amazon.com book reviews.

Copyright ©2013 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.