- Articles

Bastille Day And The French Revolution (Part I): The Ancien Régime and the Storming of the Bastille

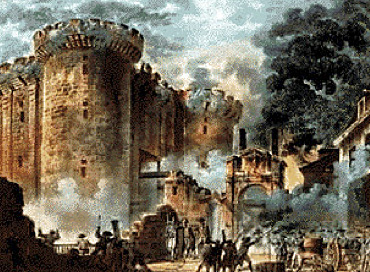

July 14 is Bastille Day, a national holiday in France that commemorates 235 years from the day a Parisian mob stormed the “infamous” prison and commenced the upheaval of the French Revolution. The collapse of Soviet communism should not deter the invocation of the dreadful legacy of the French Revolution, the same revolution that a century later inspired the even bloodier Russian Revolution and its communist aftermath.

The French Revolution began not with the clamor of the common people but with the theoretical conjectures of the blue-blooded aristocracy and the high clergy of the ancien régime, who had fallen for and become enamored with the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the views of the enlightenment.

This was convincingly demonstrated in the Assembly of Notables in February 1787, a gathering of wise men that King Louis XVI called for and convened to help him solve economic problems afflicting France, particularly the lack of solvency. This Assembly of Notables, in turn, advised the King to call the Estates General, the body which traditionally had the authority to raise taxes but which had not been summoned since 1614 during the reign of the popular king, Henry IV.

The Estates General, which sparked the revolution with the Tennis Court Oath of June 1789, became the revolutionary National Assembly. The storming of the Bastille followed in July 14, 1789. Before that notable event, however, the riots of the revolution spilling into the streets of France began not in Paris but in the streets of Grenoble, the actual cradle of the revolution, with the Day of Tiles (June 10, 1788).

The insurrection spread from there to the countryside with desultory grain riots, flaming more deliberately (from March through April of 1789) in the concerted defiance and in protest of the hated game laws protecting birds and animals for the hunting sport of the King and the nobility. Thereafter, the mobs also learned to command the streets after the Réveillon Riots (April 1789) so that by mid-summer of 1789, they had had ample practice for the storming of the Bastille.

Regardless of what the reader has been led to believe, the earliest revolutionaries were not bourgeoisie, but nobility and high clergy, many of them functionaries in the old regime, including some of the king’s ministers and advisors. Intoxicated by idealism and Rousseau’s sublime concepts of virtue, reason, equality, etc., they had set out to correct real or perceived iniquities in France. King Louis XVI’s loyal ministers saw the dangers lurking ahead, but seemed impotent to effectively protect the monarchy and solve the problems afflicting France, particularly the serious financial problem and the threat of national bankruptcy.

The truth is that in the 1780s, the old regime was of itself undergoing changes of modernity in trade, technology and laissez faire capitalism, influenced by the teachings of Francois Quesnay, the French economist and physician, and his physiocrat followers.

Unfortunately, rather than being openly welcomed by the people, these changes, liberalizing the French economy, were actually decried and resented by the masses because they brought with them insecurity and incertitude. The common people wanted cheap bread and regimentation, and the lesser nobility sided with them because they wanted to hold onto the only thing left to them — their titles of nobility and what remained of their ancient land privileges, poor as most of them might have been.

The emerging bourgeois, on the other hand, supported greater economic freedom and supported these changes. By the time the middle class realized how fast changes were taking place within the revolution, it was too late to turn back. By August 4, 1789, the National Assembly had abrogated the special privileges of the nobility and the clergy. The lofty Declaration of the Rights of Man was also proclaimed.

It was the upper crust of the high nobility and clergy militating from above (operating in the voice of Mirabeau, Siéyès, Tallyrand, etc.) who initially led, and the mob who followed. The mob learned quickly to force radical change upon the National legislature, operating with ferocious bellicosity from below. In the two years preceding the upheaval of the Revolution, the working poor, peasants, and subsistence farmers had suffered greatly, and many of them had become displaced persons because of the unusually harsh cold winter, followed by the bitter harvest of 1788-1789.

Suffice it to say, it wasn’t the bourgeoisie and working class who led the revolution without recognizing the perilous nature of their actions, but the nobility and clergy who were making war against their own class that set the revolution in motion. Simon Schama provided ample evidence for this in his widely acclaimed book, Citizens (1989). This fiery revolution became a tumbling, violent cascade that later they were unable to control. In the end, for thousands of them, if they didn’t escape as émigrés from the revolution they had helped to create — they paid the ultimate price in the guillotine.

Charlotte Corday and the Girondins

Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, walked bravely into the belly of the beast at 30 Rue des Cordeliers on July 13, 1793, and carried out the assassination of the radical, bloodthirsty Jean-Paul Marat. The savage Marat had already forced the expulsion of the brave Girondin leaders from the National Convention (June 2), and he was finalizing his plans for their arrest and grisly trip to the guillotine when Corday cut his life short.

The guillotine, though, was already covering the ground red with blood at the Place de la Révolution. The story is beautifully told in Stanley Loomis’ masterpiece, Paris in the Terror (1964). Marat’s direct participation in the bloody conspiracy to eliminate the Girondin Party was prevented by the fateful deed of the heroine from Caen, Charlotte Corday. However, his demise also served to further fuel the fire of the gathering conflagration – and ignite the Reign of Terror. Marat would turn into a revolutionary martyr, his body interred along with Mirabeau, Descartes, and Voltaire.

The Girondins, led by Madame Manon Philipon, her husband Roland de la Platiere, the journalist Pierre Brissot and the orator Pierre Vergniaud, were divided and remained oblivious to the mortal threat of Maximilien Robespierre in late 1792 and early 1793; they were for the most part young patriots and idealists, not conniving politicians or statesmen. As a party, they failed to recognize the need, or rather the necessity, for them to forge an alliance with Georges Danton, not just to win politically against the treacherous Robespierre, but for their very own survival. Some of the Girondins led by Madame Roland could not forgive Danton for his involvement in the brutal September Massacres of 1792.

While by 1791, the Constituent Assembly provided for a constitutional monarchy under King Louis XVI, the latter was short-lived and ineffective. The Legislative Assembly, which followed the Constituent Assembly (like its predecessor, the National Assembly), was subject to threat, coercion, and intimidation by the mob, the Communes, sans culottes, and the ubiquitous tricoteuses and other malcontents who had been aroused out of the cesspool of society by the calls of class envy and warfare by the usual demagogues.

The mobs were incited by the likes of Marat (L’Ami du Peuple) and René Hébert (Pére Duchesne) to apply pressure from below. The revolutionary mobs would intimidate the Assembly with their swords, clubs, muskets, and pikes marching outside the halls of the Tuileries, demanding more radical political, social and economic change, more government largesse, or else blood. The leaders of the Cordeliers Club, Georges Danton, and the Jacobin Club, Maximilien Robespierre, used threats and exhorted the people to violence in rhetorical speeches or through the printed words in the numerous revolutionary pamphlets and newspapers.

Pressure from above in this scissors strategy was used when the Assembly and later the Convention were harangued or threatened by the radical Jacobin leaders when they rose to speak and make similar demands from the rostrum of the assembly.

This scissors strategy of applying simultaneous pressure from above and below to force destructive, radical changes, and ultimately bring on dictatorship was assimilated and presented by Karl Marx in the next century as a form of political and economic theory, the class struggle of dialectical materialism (also borrowing from Georg Hegel’s dialectics). This blueprint was used by 20th century totalitarians, particularly communists, in their quest for and consolidation of power.

In the social democracies of the 20th century, this strategy, in a milder form wrapped in “compassionate” public welfarism and social concern, is still used today effectively to bring change and increase the size, scope and power of the central government — socialism, at the expense of individual liberties and freedom. This still happens today in our society, when the media go searching for victims to parade in front of television cameras while leftist politicians call for more government to protect those same alleged victims who have “fallen through the cracks.”

Before the ushering in of the Terror, the French revolutionary government was not a true republic, despite its appellation, but violent “democracy” in action, degenerating brutally and chaotically into mob rule, mobocracy. The revolutionists — led by Marat, Danton, Saint-Just, Hébert, and Robespierre — unleashed a horrible monster, a monster that, in the end, they could not control, for as Pierre Vergniaud said, “The revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its’ own children.” One by one, indeed, they would be devoured by the revolutionary monster.

When the Constitution of 1793 was popularly ratified, the citizens had to vote openly under the watchful eye of the revolution’s 44,000-member Committee of Vigilance. Shortly after, the Constitution, with its lofty goals and rights, was suspended. Anarchy interspersed with tyranny was the order of the day. Eventually, the Deputies of the Convention came to rule by decree and at the pleasure of the oligarchy of the Committee of Public Safety headed by Robespierre and his ultra-radical Jacobins. At this point, the revolution jumped from mobocracy to dictatorship.

Gruesome, still one cannot help but draw subtle parallels between some of the events that unfolded during the French Revolution and the authoritarian, secular, and collectivist tendencies that have gradually, almost imperceptibly, crept into our American republic. This has taken place in contemporary American society in the name of (social/liberal) democracy and in the atmosphere of social egalitarianism (collectivism). The underlying engine is once again the incitement of the politics of envy, demands for wealth redistribution, and the concomitant calls for more growth in the size, power, and scope of the already behemoth federal government.

We learn from the French Revolution that forced egalitarianism leads to oppression, despite the assertion that equates liberty with equality. The fact is one can have personal liberty and equality of opportunity and equality before the law (blind justice), but you cannot have both liberty and equality of outcome. Liberty entails personal choice, as well as social and economic freedom that inherently produces differences in outcome (viz, inequalities); the French revolutionists never understood that.

In Part II of this essay, we will describe the legacy of Maximilien Robespierre, “The Incorruptible.”

Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D., is an Associate Editor-in-Chief and a World Affairs Editor of Surgical Neurology International (SNI; ); Clinical Professor of Surgery (Neurosurgery, ret.) and Adjunct Professor of Medical History (ret.) Mercer University School of Medicine. He served under President George W. Bush as member of the Injury Research Grant Review Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2002-05); Realclearhistory Author (2012-present); Founder & Editor-in-Chief of the Medical Sentinel (1996-2002); Editor Emeritus; Author, Vandals at the Gates of Medicine (1995), Medical Warrior: Fighting Corporate Socialized Medicine (1997), and Cuba in Revolution: Escape From a Lost Paradise (2002). His website is or http://www.drmiguelfaria.com

This article may be cited as: Faria MA. Bastille Day and the French Revolution (Part I): The Ancien Regime and the Storming of the Bastille. Newsmax.com, July 15, 2004. Available from: https://haciendapublishing.com/bastille-day-and-the-french-revolution-part-i-the-ancien-regime-and-the-storming-of-the-bastille/

Republished HaciendaPublishing.com, July15, 2014

Copyright ©2015-2019 Miguel A. Faria, Jr., M.D.